Four years ago, Africa’s first formal training for wind-turbine service technicians (WTSTs) had to be put on hold. The funding was in place and the fourth intake of candidates was ready to start in August 2017, but had to be turned away. As the South African Renewable Energy Technology Centre (SARETEC) trains specifically according to industry demands, it had been stalled by Eskom’s delays in signing the independent power purchase (IPP) agreements. The situation seemed bleak for the rural and mostly female wind-tech candidates.

Since then, however, things have drastically improved. SARETEC in Bellville, Cape Town, is offering training courses to aspiring WTSTs. It’s the only training centre on the continent with a live nacelle (the engine at the top of a wind turbine) and the course includes on-the-job wind-farm training.

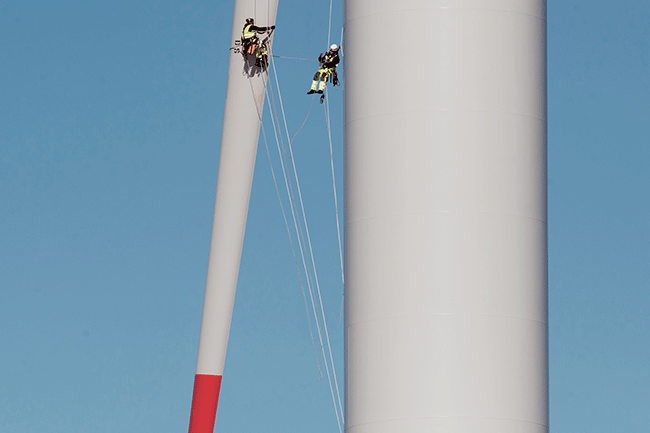

Successful applicants must be qualified in trades such as fitters and turners or in electrical, electronic or mechanical engineering (NQF Level 4). They also need to be in good health, and able to work at height and in extreme weather conditions, as their job description includes climbing the turbine tower and conducting maintenance and repair all year round, come rain or shine. The trainees, who mostly come from rural communities near wind farms, rely on funding from international development agencies and industry, where multinational original equipment manufacturers sponsor training for their local employment needs.

‘When our training began in 2016, there weren’t any benchmarks for renewable energy training in South Africa, so we developed everything ourselves – under the expertise of the German development agency GIZ,’ says Henk Volschenk, head of training at SARETEC, which is part of the Cape Peninsula University of Technology. ‘We’ve built strong partnerships with government, academia, industry, associations and private-sector companies in the renewable-energy space.’

The centre offers accredited formal and short courses in wind, solar PV and energy efficiency, which include basic safety as well as solar training and PV GreenCard assessments.

The latter is a seal of quality and safety for solar PV rooftop installations, launched in 2017 by the South African Photovoltaic Industry Association (SAPVIA). The industry body, which represents 300 companies, plans to make the PV GreenCard mandatory for all official installations. Installers wanting to be included in the accredited database need to pass a theoretical and practical test.

‘In a market with no regulations or standards, the creation of a suitably skilled workforce was of utmost importance,’ according to Niveshen Govender, COO of SAPVIA. ‘Through the training partners, the programme has trained more than 700 candidates, 300 of which have been assessed and accredited.’

This demand is set to grow substantially as South Africa’s latest Integrated Resource Plan (IRP2019) has allocated an additional 6 000 MW of solar PV utility-scale plants (to be brought online by 2030) as well as 6 000 MW of embedded generation. Govender notes that job opportunities in the sector range from manufacturing to engineering and design, to finance and legal professionals. ‘We estimate that the largest number of jobs come from the construction of utility plants as well as installers of solar PV rooftops,’ he says.

The employment potential in wind power is similarly promising. The South African Wind Energy Association (SAWEA) expects the extra annual wind energy capacity of 1 600 MW between 2022 and 2030 to translate to 640 individual towers and 1 920 wind-turbine blades each year. This means additional training of wind technicians as well as on the manufacturing side. The existing wind-tower factory in Atlantis, Western Cape, has already created 340 direct and 200 indirect jobs. It has the potential to create 1 360 direct and 800 indirect jobs, according to SAWEA.

‘The bulk [around 70%] of job creation in renewable-power generation is within the high-skilled labour group, defined as workers with an educational attainment level above Grade 12, although employment is also created in other skill groups,’ states a 2019 Cobenefits study on future skills and job creation through renewable energy in South Africa. ‘The employment gains obtained are dependent on the availability of a skilled labour force. While not optimal for localisation, the “importation” of key high-skilled labour could be considered as an interim measure to address potential critical skills gap that arise.’

SARETEC is already working closely with technical and vocational education and training (TVET) colleges to close renewable-energy skills gaps as they arise. ‘We won’t be able to meet the increasing training demand ourselves and are thus empowering other training providers across South Africa,’ says Volschenk, highlighting growing interest in SARETEC’s expertise from other African nations too. ‘Our mandate includes quality assurance and monitoring of training to ensure a high standard of technicians.’

He says that the West Coast College in Atlantis and Eastcape Midlands College in Uitenhage are set to offer accredited WTST training. Furthermore, SARETEC will soon provide a two-year qualification for solar PV service technicians (SPVSTs) that complies with the Quality Council for Trades and Occupations. ‘It’s a four-part qualification that progresses from solar PV mounter via solar PV installer, to solar PV farm technician, to standalone-systems technician,’ says Volschenk.

To further boost solar PV training capacity, seven TVET colleges across South Africa have each sent three lecturers on a 10-month training programme at Nelson Mandela University and Volkswagen’s artisan-training centre in Uitenhage, in order to offer the SPVST qualification in the near future.

The demand for renewable-energy training keeps changing. ‘Some five years ago, the focus was on the solar thermal side, due to the government’s large national solar water-heating [SWH] refit programme,’ says Willie Grasse, operations director at MSC Artisan Academy in East London. ‘That slowed down after Phase I, but the potential roll-out of a Phase II has renewed interest.’

The demand for solar PV rooftop training was very high when the initial IPP programme was announced, but then faded as a result of uncertainty within local municipal regulations, according to Grasse. ‘The current climate is creating new demand, specifically from the private sector.’ While most candidates in the PV rooftop installer programmes are either already employed, self-employed or planning to become self-employed, he says the SWH candidates used to comprise unemployed youth in government job-creation initiatives. Recently, the private sector has also shifted towards SWH training, following compliance requirements by the Plumbing Industry Registration Board.

Meanwhile, a regional SWH programme that has trained more than 3 000 participants in 100 courses in Botswana, Lesotho, Mozambique, Namibia, South Africa and Zimbabwe has been extended into a fourth phase. One focus area of the Southern African Solar Thermal Training and Demonstration Initiative (SOLTRAIN), which is funded by the Austrian Development Agency, is the increase of technical skills at different competency levels in the SWH value chain.

Solar thermal often involves the upskilling of already qualified plumbers. ‘It’s not such a big leap from working with a gas or electrical geyser to a solar one,’ says Karen Surridge, centre manager of the Renewable Energy Centre of Research and Development at the South African National Energy Development Institute, which is a local implementation partner of SOLTRAIN.

She cites a project at Hoedspruit Air Force Base, Limpopo, where SOLTRAIN’s thermosiphon course upskilled 20 artisans from the Department of Defence. A top participant and qualified plumber, Byron Johnson, commented that ‘the course was interactive and, as a hands-on person, I excelled when the group would simulate real situations’.

Yet another initiative is the Developing Developers programme. Launched in September through a partnership between SAPVIA and SAWEA, its aims – among others – are to enhance the local skills base, address the gaps in the local industry and ensure effective knowledge sharing across the South African value chain.

‘Historically we have relied on much-needed foreign investment and know-how, but the time has come for South Africans to step up and step into the role of developer,’ says SAPVIA’s Govender. ‘We have so much to gain by empowering local communities and upskilling individuals.’

Basic artisan skills form the foundation for many jobs in the broader energy sector. Adrian Strydom, acting CEO of the South African Oil and Gas Association (SAOGA), says the local workforce is ready for the oil and gas economy to take off. ‘We couldn’t develop specialised [oil and gas] skills as the local industry is still in its infancy, so instead we focused on foundational cross-cutting skills. A study on the 1 000-plus artisans SAOGA has developed over two years shows that 95% are now employed or have started their own small business.’

Many are working in manufacturing as well as in the wind and solar sector. Strydom adds that training for more specialist oil and gas roles can be done rapidly ‘as the need arises’.

This appears to be the common denominator with the renewable energy sector, where training providers are ready to train more technicians as soon as government gives the green light for legislative certainty.