While the world economy has stabilised to some extent, the mining industry continues to adjust to the new post-2008 funding environment – and to the noticeable slow-down in demand for some of the mineral commodities that drove an almost unprecedented global mining boom in the first decade of the century.

As part of this change, there has been a rebalancing between exploration, project development and production. Major mining houses have cut their exploration budgets to focus on getting the most from mine production, while juniors and mid-tier exploration companies are working feverishly to take their most-promising assets to production.

This refocusing is evident in a recent report by Natural Resources Canada, one of the world’s busiest mining jurisdictions, which noted that combined exploration and deposit appraisal expenditures fell 41% between 2012 and 2013, from US$3.6 billion to US$2.1 billion. Significantly, expenditures at the deposit appraisal stage, which follows earlier exploration, remained almost constant at around US$1 billion.

The same shifts are true for mining in Africa. As SNL Metals & Mining executive David Cox argued at this year’s Mining Indaba in Cape Town, in comments reported by South Africa’s Independent Group, exploration spending could fall between 15% and 20% this year.

The drop will most likely be smaller than the decline expected in jurisdictions such as Canada or Australia, reflecting the highly prospective characteristics of many African regions that remain relatively underexplored. Nevertheless, it indicates the pressure on mining firms to get the most out of their exploration budgets by employing cost-effective technologies that reveal viable deposits in the shortest possible time.

Many African mining houses will also be seeking to quickly define and obtain formal reserve estimates for the deposits they have already identified, in a race to garner the reduced amount of development financing available internationally. On the African continent, there are potentially still a number of significant outcrop mineral formations to be found – as well as many wholly subterranean deposits – and the full range of exploration technologies is needed.

The selection of these technologies is often informed as much by their costs and energy efficiency as their cutting-edge capabilities, and the choice of some exploration technologies is also shaped by local regulatory concerns. The earlier stages of exploration often take place at altitude using airborne gravimetric or magnetic surveys to cover wide areas, in some cases with unmanned, drone-type aerial vehicles.

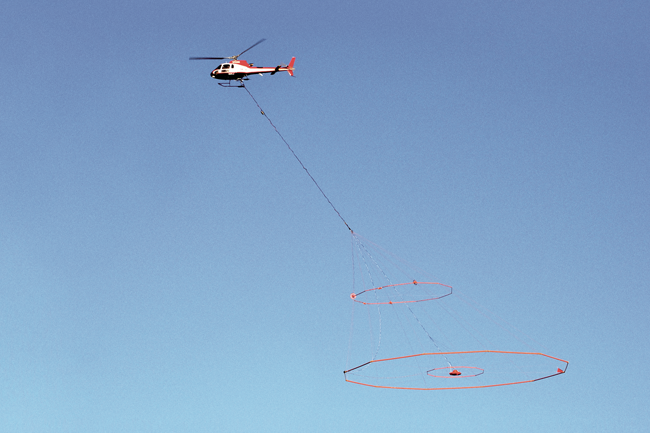

Recent proprietary sensing methods have also led to rapid improvements in this area. In Ghana, for example, airborne transient electromagnetic (TEM) survey methods – notably those using versatile TEM technologies operated by Canadian firm Geotech – are used to locate gold-bearing formations up to 400m below the surface in the country’s south-western greenstone belts.

Also in Ghana, researchers working with Newmont Mining have been testing the utility of ground-penetrating radar surveys for detecting mineralisation – a low-cost method that has not been used in the country before.

Once deposits are roughly located, moving from historical geological data to airborne surveys and then to on-the-ground analysis, exploration companies are able to draw on new technologies to analyse minerals both in situ and those extracted in drill cores. These include portable X-ray analysers and short-wave infrared spectrometers – for example the TerraSpec range produced by ASD Inc, which can assess the potential mineralisation of rock samples in the field.

When drill cores are obtained, geologists can turn to inductively-coupled plasma mass spectrometry, which enables a simultaneous and precise measurement of many different minerals in a single sample. From there, they could potentially apply innovative inversion algorithms to gain an idea of the broader shape and extent of a deposit.

Major mining houses have cut their exploration budgets to focus on getting the most from mine production

Research currently under way at Australia’s Deep Exploration Technologies Co-operative Research Centre also has the potential to revolutionise exploration drilling itself, both in costs and portability, which is essential for many African situations.

The centre hopes to adapt coiled tube-drilling techniques, presently employed to clean wells in the oil and gas industry, for hard-rock minerals exploration. Should it be perfected (though this by no means a certainty), this could be transformative for small companies that now face rapidly escalating drilling costs.

While sourcing and deploying the correct exploration technologies may be one challenge facing Africa’s mining firms, another is rapidly defining the resource of a deposit so that a company can make an investment case to financiers and support its share price. Since the days of the notorious Bre-X scandal in 1997 – which saw the value of a company fall from CA$6 billion (around US$5.5 billion) to nothing after its gold reserve statements were shown to be fabricated – investors are more circumspect about who they recognise as a ‘qualified person’ to certify an economically viable mineral reserve.

Here African mining companies are able to draw on local certification expertise as well as the presence of the major international firms, such as SRK Consulting and SGS, which provide computer-assisted modelling of ore bodies and subsequent certification of reserves to the international JORC and NI-101 standards.

Earlier this year, German consulting company DMT also expanded its African presence after it acquired a majority stake in South Africa’s Kai Batla Minerals Industry Consultants – a sign of the increased local demand for expertise in this pivotal stage of the mine-development process.

The importance placed on quickly firming up an exploration project is evident in the rapid development of West African iron ore projects.

In Gabon, several companies are seeking to attract investors by defining a viable iron ore resource for direct shipping. Earlier this year, South African mining company Assmang entered into a US$19 million investment agreement with explorer IronRidge – the latter had indicated an exploration target of over 1 billion tons (Bt) at 60% iron ore, following gravimetric surveys at its Belinga Sud project in north-east Gabon.

Meanwhile, AIM-listed company Ferrex has recently stated an exploration target of 540 to 900 million tons (Mt) at 25% to 40% iron ore, for its Mebaga project, while ASX-listed Apollo Minerals’ Kango North project has an exploration target of 2 Bt to 3.5 Bt at 30% to 40% iron ore.

These companies are seeking to gain a first toehold on the route to reserve certification, using improved early-stage technologies to assess the broad shape of their deposits. More work is required before these can become a bankable mine.

Also in West African iron ore, African Minerals Ltd has been enlarging the size of its certified resource base at the already productive Tonkolili mine, certifying an additional 59.5 Mt of direct-shipping ore through the services of SRK Consulting. In this sense, a reliable and competent person, working for an established firm, is as important as any high-tech geosurvey method in the eyes of investors.

Techniques are only as good as the humans who deploy them and analyse the results – people remain the highest form of technology

Companies with established mines across various minerals are using new physical technologies for brownfield exploration as a way of supporting their share price and operational longevity. Anglo American, for example, focuses on brownfield exploration as a matter of policy.

Techniques for improving the reserve base and the planning of brownfield sites include new ‘down the hole’ technologies. These reduce the need for repeated core drilling by enabling in-hole spectrometry of the mineral bodies as well as hyperspectral core mapping (extremely detailed vertical modelling of deposits).

Big companies may opt to develop or source these technologies in-house. Those with fewer resources, however, must obtain them second- hand through specialist procurements firms, or by employing contractors that often deploy proprietary techniques.

Many of the latest technologies remain out of the cost-reach of most mining companies in Africa – or they are not used because they are not easily available in more remote regions. With regard to smaller firms, however, a great deal can still be achieved with time-honoured techniques. In all cases, techniques are only as good as the humans who deploy them and analyse the results – people remain the highest form of technology.

To this end, there is an urgent need for African states to intensify the training of local specialists and, where possible, fund local research organisations such as South Africa’s Council for Scientific and Industrial Research or the Wits Mining Research Institute.

These and similar organisations are set to reduce the reliance of local firms on external technology providers – boosting skills transfer and improving the long-term capabilities for mining on the continent.

By David Bannister

Image: Geotech Images