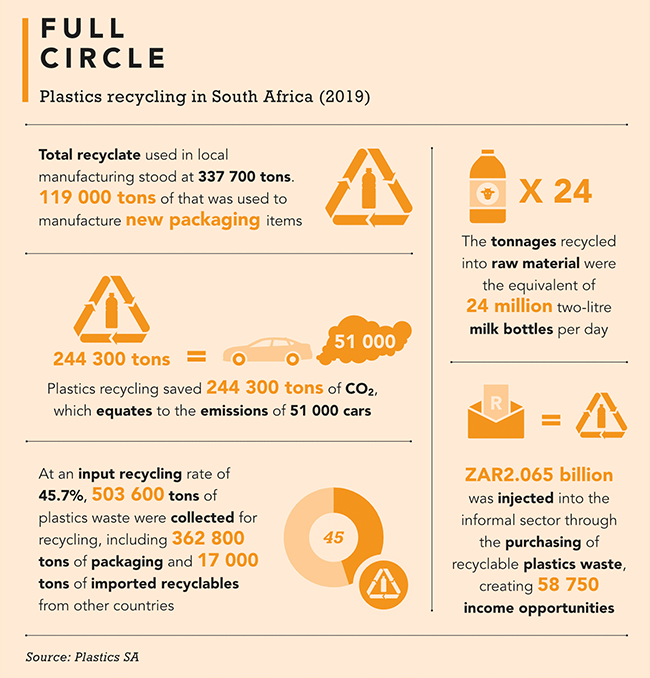

South Africa has some of the highest recycling rates in the world. In fact, the plastics recycling sector has out-performed some developed countries for years. During 2019, 503 600 tons of plastic waste was collected, while 337 745 tons of recycled material was converted into new products, according to Plastics SA. Similarly, the paper-recovery rate of 68.5% is well above the global level of 59.3%, according to the Paper Manufacturers Association of South Africa (PAMSA). Jane Molony, acting CEO of Fibre Circle, the producer-responsibility organisation for the paper and paper packaging sector, says that extended producer responsibility will go a long way in advancing infrastructure and systems, to not only make the recycling value chain stronger but also hold producers and importers accountable to their environmental and recycling commitments. ‘For a recycling industry to be sustainable, there needs to be product available for collection,’ she says. ‘We need more companies to recognise the environmental value of paper products – that it comes from a renewable resource, ie sustainably farmed trees; that paper stores carbon; and that paper products need to be designed for recycling.’

Despite these great recovery rates, the country does not have widespread separation at source – this being the setting aside of post-consumer and household waste materials at the point of consumption, before they enter the waste stream destined for landfilling. So where is all this post-consumer material coming from? Primarily, informal waste reclaimers – or waste pickers. According to the CSIR, reclaimers collect 80% to 90% of the post-consumer packaging and paper that enters the recycling value chain in South Africa. Theirs is a system that has been dubbed ‘separation outside source’. While an exact figure is not available, experts estimate that there are between 60 000 and 90 000 informal reclaimers working in the country, sifting through waste to salvage the recyclables that others so thoughtlessly throw out.

‘Without informal waste reclaimers, we wouldn’t have a recycling industry,’ says Melanie Samson, senior lecturer in the Wits School of Geography, Archaeology and Environmental Studies. ‘Government has only recently become interested in recycling and very few municipalities have official recycling programmes. Not a single large metropole has a comprehensive city-wide recycling programme in place.’

Waste reclaimers, says Anele Sololo, general manager of RecyclePaperZA, are a vital link in the sector’s value chain. ‘Most of South Africa’s paper-recovery success has been due to industry-driven programmes and the efforts of informal waste collectors. For the past three years, South Africa’s paper recovery rate has been around 70%.’ Sololo adds that there is still indifference and ignorance around recycling among consumers, something which the paper industry addresses continually.

In South Africa, household separation at source is not mandatory. Seeing this as an opportunity to earn income, reclaimers salvage recyclables from kerbside waste and sell what they collect to buy-back centres. The buy-back centres then supply the recovered material to recycling mills. Despite the significant role they play in the recycling value chain, reclaimers’ efforts could be better acknowledged. ‘The industry and government need to officially recognise the role that reclaimers play in the system and partner with them,’ says Samson. ‘When municipalities have started setting up official recycling services, they’ve contracted this out. These private companies go into areas where reclaimers have been working for decades and dispossess them. These companies are not collecting anything new; they’re collecting the same materials that reclaimers were. So [they] are being paid a service fee to earn a profit, whereas the reclaimers, whose sole income relied on selling what they collected, are left with no income at all. They’re not increasing recycling rates. They’re creating starvation.’

Samson and her team, through a three-year research programme, conducted an analysis of reclaimers’ experience integrating into municipalities, and facilitated the development of the Guideline on Waste Picker Integration for South Africa. They also developed a seven-step process that municipalities can undergo to develop and implement integrated separation-at-source initiatives. The guideline maps out what reclaimers do, why they are essential to the recycling economy, why we need reclaimer integration, and how to achieve it.

Samson is currently also running a project (funded by the government of Japan) that provides training and capacity-building support to municipalities, industry and reclaimers to meaningfully integrate reclaimers. ‘We’re working with key stakeholders and designing these programmes to support municipalities and industry in working with reclaimers,’ she says. ‘We need reclaimer integration […] As we move towards a circular economy, we want to increase recycling rates and improve livelihoods, not destroy them, particularly in a developing country like South Africa.’

Samson believes the best way to increase material collection rates is to pay reclaimers a service fee for collecting recyclables, as this gives them an incentive to collect low-value items. ‘In South Africa, reclaimers are not paid for the recycling service they provide, whereas in other countries, they are. For example, in Brazil, the reclaimer co-operatives are paid by municipalities to collect recyclables.’

In mid-2019, the African Reclaimer Organisation (ARO), in partnership with Wits University and Unilever South Africa, announced a pilot project called Building an Inclusive Circular Economy: Recycling with Reclaimers. The Johannesburg-based project sought to change community behaviour on waste management and perceptions of reclaimers, as well as formally integrate reclaimers into the value chain. It was also the first time that reclaimers would receive payment for their work – this in the form of a per-kilogramme collection service fee set at 50c a kilo.

Reclaimers were registered and given a uniform and name tag, as well as clear bin bags that they distributed to residents of Brixton and Auckland Park (the areas earmarked for study). They directly engaged residents, asking them to separate out their recyclable materials each week, and educating them on what can and cannot be recycled. Week after week, the reclaimers then visited these areas to collect the filled bags of recyclables, leaving empty ones in their place. During the 10-month pilot, 55 reclaimers collected more than 150 tons of recyclables from the two suburbs. The process was fully documented so that, together with the seven-step guideline developed, it can offer municipalities a concrete idea of what the collection service will look like.

Samson says the pilot project has changed the way that residents see and value reclaimers. ‘Putting up billboards doesn’t change behaviour, but when reclaimers directly engage residents, and residents start to have a personal relationship with reclaimers, they understand that separating their materials will improve this person’s daily life, and will support their families. It’s a much stronger encouragement,’ she says.

Luyanda Hlatshwayo has been working full-time as a reclaimer in Johannesburg since 2011. Asked how he finds this line of work he says it is a ‘very unbalanced industry’ and that many people do not fully understand the value of the work that reclaimers do. ‘We do the most difficult work in the whole value chain and we save municipalities millions. But it’s like the old working system of importing cheap labour to get the work done,’ he says.

Hlatshwayo describes the pilot project as an important step in creating an inclusive circular economy – one where each and every person in the value chain plays a part – and where the people who actually do the work get the compensation, he adds. It also proved a lot of things, he says, such as the existence of ‘a proper working system that doesn’t need to be disturbed’. There was a lot of good to come from the pilot, says Hlatshwayo, along with much positive change – particularly when it came to engaging residents. ‘The education that happened was eye-opening. We started seeing residents opening up their homes to reclaimers, asking them to come in and see what is and is not recyclable.’

Eli Kodisang, a co-ordinator at ARO, says the feedback they have received about the project has been ‘overwhelmingly positive, especially from the residents’. He says the project started off without much support, and with much suspicion. ‘People were unsure that it was possible to have the informal sector pick up material and then leave the area cleaner than it was,’ he says. ‘I think we’ve moved from a situation where residents didn’t know what these people walking around the streets were doing, to them now having a deeper insight and understanding.’

There is a great need for government and the industry to recognise the importance of the informal sector, says Kodisang. ‘What we’ve seen mostly thus far are the kinds of projects that marginalise the informal sector and put the private sector into first place,’ he says. ‘It’s as if we have to prove the depth of knowledge that we have about the recycling process, to constantly prove ourselves and our worth.’

Its evident success aside, Samson says the project was about more than just improving recycling rates. ‘Johannesburg is one of the most unequal cities in the world. Through this programme we are transforming persistent social relationships and creating more inclusive communities and a more inclusive city,’ she says. ‘It is a social and political transformation as well as an environmental and economic transformation.’