Frustrated with her career in the corporate world, Mary Phillips decided in 2012 to quit her job and start her own business. She chose paper recycling and, despite some initial difficulties, soon began seeing good returns. Now her Eastern Cape-based start-up business provides employment for three permanent staff members, pays 10 waste collectors on a regular basis and is a source of income for 18 casual workers. And Phillips believes her best days are still to come.

Northern Cape entrepreneur Siphamandla Ntshangase has a similar success story. An industry pioneer in a job-stressed region of the country, Ntshangase set up a recycling business in Kimberley. He formed a relation-ship with a major supermarket chain where he has the exclusive rights to remove dry waste from 12 outlets.

Ntshangase’s business currently supports 12 employees and their families, and he has hopes to expand. ‘Our plans for the future include buying baling machines and hiring many more people from local townships,’ he says. ‘Our forecasts suggest that within the short term we should be collecting and distributing about 170 tons of paper and plastic a month.’ His long-term aim is to develop a processing plant in which paper and plastic waste is transformed into usable raw material for the production of new products, so completing the recycling circle.

These are just two of the many success stories to come out of South Africa’s bourgeoning recycling industry – one that formally employs thousands of people and that has created informal employment opportunities for thousands of others, with the potential for even more.

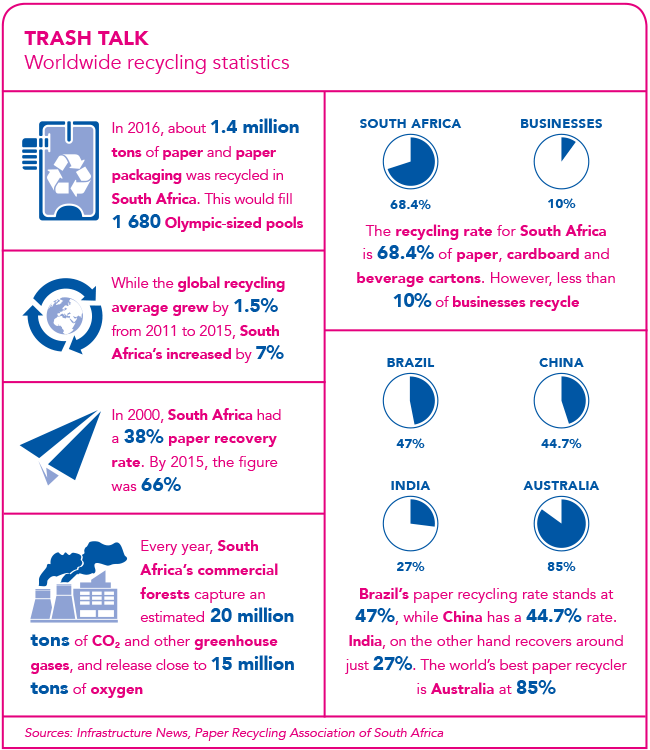

In 2016, 68.4% of recoverable paper was recycled. South Africa’s paper recovery rate has increased by 2% year-on-year and is well above the global average of 58%, according to the Paper Recycling Association of South Africa (PRASA).

Ursula Henneberry, PRASA operations director, puts this into perspective. ‘One ton of recycled paper saves 3 m3 of landfill space. The 1.4 million tons of recyclable paper and paper packaging diverted from landfill in 2016 is equivalent to the weight of 280 000 African elephants. The same volume would cover 254 soccer fields or fill 1 680 Olympic-sized swimming pools.’

Henneberry believes that South Africa’s successful paper recovery can be largely attributed to the informal collection sector. ‘Informal waste collectors are the recycling industry’s unsung heroes,’ she says. ‘Although they are often seen as a nuisance – especially when hauling overloaded trolleys along busy roads – these collectors contribute significantly to the diversion of recyclables from landfill, and earn a living by recovering recyclables and selling them to buy-back centres. The average waste collector can start without a cent in his or her pocket and end the day with enough to buy food for the table.’

From street collectors to those formally employed in the industry, paper recycling creates meaningful employment for around 37 000 people, according to Henneberry. Meanwhile, the forestry paper-recycling sector employs as many as 150 000 people, she adds, with each PRASA member having its own scheme, from owner-driver curbside collection to buy-back centres around the country.

Long-term sustainable recycling requires long-term sustainable investment, which includes spending on recycling facilities that create a market for recyclable materials. ‘This will allow the approximately 100 000 people who rely on constant volumes of recycled material to earn a sustainable living, from factory employees to entrepreneurs and small-business owners,’ says John Hunt, MD of Mpact Recycling.

According to Hunt, a robust global demand for recyclables creates markets for all waste collectors in the industry, from the large operators to the curbside gatherers. ‘If there is no continuous investment and sustainable industrial manufacturing capacity in South Africa, there will be a limit as to how much people are able to recycle. No one will want to wake up in the morning and collect material that cannot be sold,’ he says.

Dudu Feleza is the owner of the Kempton Park buy-back centre. She started the operation in 2000 with the assistance of Mpact Recycling. Mpact was also one of her first customers, purchasing her recyclables and helping her earn the income she needed to get her business completely up and running. Today, Feleza employs eight people – six at her premises and two out-sourced to clients – and regards herself as a business-woman who has been empowered by the recycling industry.

‘I have 25 trolleys at my premises, which allow the collectors to earn an income and support their households,’ she says. Feleza’s buy-back centre is one of more than 40 that supply Mpact, and one of seven such women-owned facilities in Gauteng.

Remade Recycling’s waste-management solutions focus on buying and accumulating large volumes of all grades of recyclable matter and selling it as a raw material input source to South Africa’s leading manufacturers of products made from recyclables. The company has nine branches across South Africa, and has created a comprehensive network of buy-back centres throughout Gauteng. These centres cater to more than 1 000 street hawkers who make a living through collecting recyclable material and selling it to the buy-back centres for a price-per-kilo rate.

The organisation actively supports informal waste collectors and tries to empower these individuals by offering opportunities within the recycling structure, such as the buy-back centres. ‘For people who are prepared to work hard, creating an income stream from recycling is quite possible,’ says Michella Hattingh, Remade Recycling’s group marketing and PR manager. ‘Fortunately for us, in South Africa we have the National Environmental Management Waste Act of 2008, which forces people to recycle. This means that there are endless opportunities for the development of entrepreneurs in the recycling industry.’

Schools are also an important part of the recycling equation and Mpact co-ordinates an annual competition in Gauteng, KwaZulu-Natal and the Western Cape to see which institution collects the most paper. Mpact says that Veritas Junior College in Johannesburg has collected almost 35 tons of paper since it became part of the Ronnie Recycler programme in 2014. The initiative aims to encourage learners to collect paper and other materials for recycling. In 2016, approximately 170 000 learners were reached through the programme.

In the Nelson Mandela Bay Metro, the Waste Trade Company is a leader in the local recycling and waste-management sector. One of its divisions is the Schools Recycling Project – started in 2009 as part of the company’s social responsibility campaign. The project proved so popular that it became an ongoing initiative and has thus far signed up 280 schools in Adelaide, Despatch, Port Elizabeth, the Sundays River Valley and Uitenhage.

The project empowers children with knowledge and the principles of recycling by involving them in various hands-on educational activities. It provides schools – as well as churches and NPOs – with the resources, educational and motivational tools to recycle. Participants also benefit by receiving a financial rebate for their recyclable materials.

Kay Hardy, general manager of the Waste Trade Company, believes that education is fundamental in ensuring a sustainable future. According to her, close on 3 000 tons of waste have been diverted from landfill over the past five years because of the schools project. As such, in June last year, the Waste Trade Company received an award for the Best Recycling Public Education Programme in South Africa.

To empower entrepreneurs and unemployed youth in the waste-management and recycling sector, PRASA has delivered several training courses through the Fibre Processing and Manufacturing Sector Education and Training Authority. Henneberry says that the training targets people through youth centres, faith groups and local industry associations, with partnerships between PRASA and local municipalities playing a vital role. The four-day workshops adopt a practical approach to a variety of key business basics, including entrepreneurship, communication, finance, and research and planning. By giving trainees a platform for learning and earning, they can translate their ideas into income-generating action, she says. ‘We are so often impressed by the “can-do” attitude of our trainees. Many of PRASA’s participants have moved up the ladder, from hauling a trolley to driving a truck, and subsequently paying it forward by employing others. To date, PRASA has trained around 5 000 since the programme began in 2010.’

Henneberry believes there are plentiful opportunities for companies operating in the paper recycling industry, across the value chain – from collection to processing. ‘Every business likes to be better at reducing its environmental footprint. Knowing and sharing the benefits of your paper recycling efforts will help each person strive to do more.’

There is also great scope for job creation, she says. ‘Big and small companies as well as informal collectors make money and employ people through the recovery and processing of clean, quality recyclable paper.’