The UN’s International Decade for Action ‘Water for Life’ (2005 to 2015), in which it aimed to halve ‘the proportion of people without sustainable access to safe drinking water and basic sanitation’ as part of its efforts to fulfil its commitment to the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) came and went.

This was an ambitious objective that met with notable success: 91% of the global population now uses an improved drinking water source, compared to 76% in 1990. Eastern Asia, South-Eastern Asia, Southern Asia and Western Asia all met their drinking water targets.

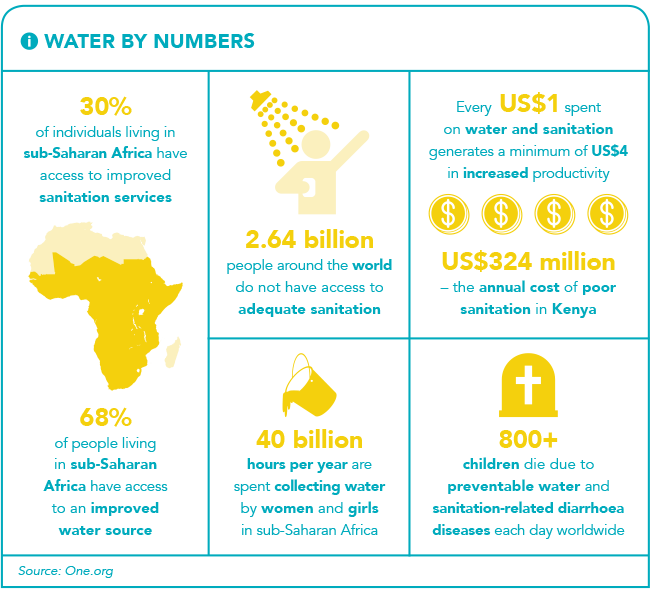

Sub-Saharan Africa, however, did not, gaining only a 20% improvement in access. The continent is home to nearly half of the 780 million people globally who still do not have improved drinking sources. Most devastating of all, an estimated 800 children die every day from diarrhoea, spread through poor sanitation and hygiene. To them, the UN’s successes are meaningless.

Obviously, clean water is essential for survival, but there are more insidious, long-term implications as well. A lack of basic sanitation keeps those caught in a cycle of extreme poverty trapped there. When individuals are constantly ill, and those who are healthy are constantly caring for the ill or travelling long distances to collect from a clean water source (more than 40 billion productive hours are lost each year to fetching water in sub-Saharan Africa, according to aid organisation Lifewater), very little time and energy can be given to finding and keeping a job or securing basic essentials.

Clean water is needed for farming and for businesses to thrive. So why has sub-Saharan Africa lagged behind? ‘Each country has its own arrangement to manage water and sanitation, which is very weak in sub-Saharan Africa,’ says Tamiru Abiye, professor of hydrogeology at the School of Geosciences, University of the Witwatersrand, and manager at the Africa Groundwater Network. ‘Only South Africa has managed to provide water and sanitation for over 75% of its population.

‘The greatest challenge for most countries is an institutional separation between water and sanitation. In South Africa – four years ago – the Department of Water Affairs was mandated to manage the sanitation aspect, which is the correct arrangement.

‘In sub-Saharan Africa, financing for clean water supply and sanitation is insufficient and the institutional capacity for delivery of the service is also very weak.’ Abiye adds that this danger was observed in the lack of achievement in the MDG. Subsequently, the UN launched further Sustainable Development Goals in 2016. Goal number six is specifically dedicated to ensuring access to water and sanitation for all.

According to the UN, ‘there is sufficient fresh water on the planet to achieve this. But due to bad economics or poor infrastructure, every year millions of people – most of them children – die from diseases associated with inadequate water supply, sanitation and hygiene. By 2050, at least one in four people are likely to live in a country affected by chronic or recurring shortages of fresh water’.

Unfortunately, and unsurprisingly, there are no silver bullets. ‘There is wide agreement that there is no single specific intervention that could improve water supply and sanitation in sub-Saharan Africa, given the wide diversity of circumstances on the continent,’ says water security expert Mike Muller, a visiting adjunct professor at Wits University’s School of Governance.

‘If there is a common message, it is that the effective delivery of public services will only be achieved if there is good governance and adequate funding. In this context, good governance can also help to make more funding available, both by making existing resources go further but also by attracting more money to the sector.’

The private sector can be a valuable ally to governments as most countries require infrastructure that is well beyond the financial capacity of the public sector. Public-private partnerships (PPPs) can be adapted to suit specific circumstances and have in many cases proven successful. For example, Gabon privatised its water and electricity services 20 years ago, and obligations have been met in all but some of the more isolated rural areas, while financial performance has improved steadily.

In Senegal, Senegalaise des Eaux has been managing the water system since 1996, which has resulted in a 165% increase in household water connections. This is an excellent example of a high-functioning PPP in a fragile country, according to the World Bank, and has been studied as a model that could be adapted to other African countries.

Straightforward investment is also needed. In Burkina Faso, the World Bank’s intervention (along with other donors) has resulted in a massive increase in access to water in the country’s capital city, Ouagadougou, where the water was running out. The population had doubled between 1985 and 2000, and only 30% of the population was benefiting from the water supply system. Now, thanks to strategic investment, 94% of the city’s population has access to clean water.

In Madagascar, the World Bank’s investment in boreholes brought the average walking distance for fetching water from 3 km to less than 500m. Indeed, boosting access to groundwater – where available – is key in bringing potable water to the disadvantaged. ‘When South Africa was complaining about the impact of drought on water supply and agriculture, countries with an arid climate such as Botswana and Namibia did not,’ says Abiye. Why? ‘The answer is simple. They rely on groundwater rather than rivers for drinking, industrial and irrigation water supply. The have got several well fields that supply different economic sectors, while groundwater is undervalued in South Africa.’

While investment, infrastructure development, community education about hygiene practices and an empowered political, legal and regulatory framework are where major advancements are likely to occur, new innovations and technologies are also of vital importance.

One area where these are expected to make an impact is by utilising acid mine drainage (AMD) from old mines in South Africa. Kevin Roelofse, product manager for dewatering at Weir Minerals Africa and Middle East, says there are innovations that have the potential to contribute significantly to the quality of water, including converting AMD to potable water and utilising this in drip irrigation to grow crops on expanses of underutilised mining land. ‘Not only will this contribute to the socio-economic upliftment of society – particularly SMMEs that are dependent on mines for their business – but it will provide alternate revenue streams for communities in cyclical mining downturns.’

According to Muller: ‘Water supply and sanitation is based on a large range of relatively basic technologies. There are many niches in which technological innovation is making a contribution, such as more water-efficient toilets and new treatment technologies for specific wastewater problems.’

In 2011, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation issued a challenge to redesign the humble toilet, in an effort to provide better sanitation and improve the lives of those who need it most. A number of entries received grants, including a solar-powered toilet, but recently it is a waterless toilet that uses nanotechnology which seems most promising. Not only is the Nano Membrane Toilet waterless and easy to use, it actually creates water and electricity, and is aimed at urban areas.

One company that has perfected a simple, cost-effective toilet solution is South African-based company African Sanitation Outsourcing. They have developed a solar-powered, chemical-free toilet that can be easily set up to service a family. In partnership with compost container manufacturer Joraform and the Department of Rural Development, the toilets are the first step of a cycle to transform human waste into a pathogen-free compost. Decomposed faecal matter is collected from households and processed through Joraform’s composting technology for another four weeks. The end result is a pathogen-free compost that can be widely utilised on small farms.

From high-tech to low… another fascinating, almost comically simple innovation is that of SODIS (solar water disinfection). It involves – essentially – placing a large, clear plastic bottle full of water on the roof for around six hours (maybe two days if it’s cloudy), and hey presto, you have disinfected water. The combination of UVA radiation and increased water temperature inactivates bacteria and viruses.

SODIS is an initiative of the Swiss Federal Institute of Aquatic Sciences and Technology. Around 250 000 people alone in the Kibera informal settlement in Kenya, Africa’s largest such settlement, are said to benefit from this technology every day to get safe drinking water. A case of science meets simplicity.