The water-related terms ‘day zero’ and ‘new normal’ have crept into sub-Saharan Africa’s vocabulary. The former denotes the date the municipal water supply is expected to run dry, while the latter describes the scenario of water scarcity and endemic drought to which the region needs to adapt.

The most recent African metro affected by a water crisis is the City of Cape Town, where day zero is expected to arrive in March 2018 if consumption is not drastically reduced. ‘The day or month of this happening is, however, not as important as what we do now to avoid such a time,’ said Cape Town mayor Patricia de Lille in October. ‘The new normal means that as a permanent drought region, we have to change our relationship with water as a scarce resource and augment our supply with alternative non-surface sources.’

Many African countries have already been improving their water-management campaigns to save the resource and find innovative solutions to the problem, often with the help of the private sector.

In 2015, Kenya introduced the Upper Tana-Nairobi Water Fund in a public-private partnership – the first of its kind on the continent – to address water challenges. East African Breweries, Coca-Cola, Nairobi City Water and Sewerage Company, and electricity provider KenGen are part of this partnership, which involves corporates, utilities, conserva-tion groups, government and farmers. The fund is used for watershed protection, reforestation and other activities in the upstream water conservation of the Tana river.

Other parts of Africa, notably Morocco and more recently Ethiopia and South Africa, have made headlines for their use of ‘fog catchers’. These consist of giant mesh nets that draw moisture from the atmosphere and turn it into drinking water. And Namibia’s Windhoek has become a best-practice example of recycling treated wastewater into potable water. Public education campaigns have reduced the ‘yuck’ factor of this practice.

Abraham Nehemia, Permanent Secretary in Namibia’s Ministry of Agriculture, Water and Forestry, announced in 2015 that the country was embarking on a massive water-awareness campaign. Speaking at an information-sharing session on the status of water supply, Nehemia said: ‘We have to do things differently now. The public will be part of the whole process and we will go the extra mile to educate them in saving water. We need to work together – no water, no life.’

The country’s latest education effort features the slogan ‘Go Native’, with the aim of encouraging homeowners, schools and businesses to select only indigenous vegetation as it requires less water to grow.

Meanwhile, South Africa’s Gauteng-based bulk utility, Rand Water, has established one of Africa’s most visible water-awareness campaigns. Its message is reinforced though the ‘Water Wise’ brand, which provides water-conservation tips and news, education in schools as well as online information on dam levels and rain forecasts. The initiative partners with national and international water campaigns, such as WeedBuster Week (established by the country’s Department of Environmental Affairs), as well as with corporates, such as Unilever, in an effort to save water.

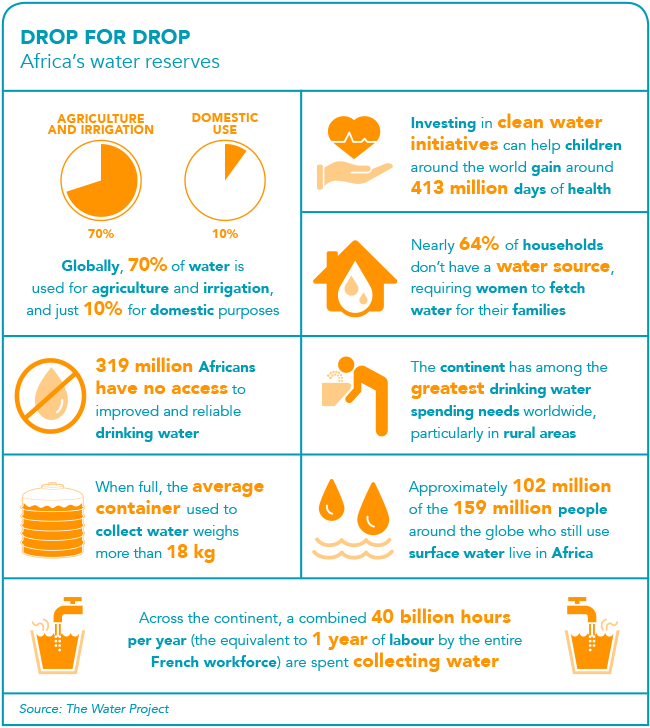

For sub-Saharan Africa, water issues have generally been linked to economic water scarcity rather than physical scarcity, because water is available – just not always in the geographical areas where it’s most needed. Economic water scarcity means that a population doesn’t have the funds to manage and access a reliable, adequate water source – something that requires significant investment in expertise, manpower, water infrastructure and technology.

However, according to the International Water Management Institute, an increasing number of nations in sub-Saharan Africa (of late, Madagascar and South Africa) are now approaching physical water scarcity.

South Africa stands out in Africa because its relatively well-developed water management and supply infrastructure (as well as the underpricing of water) has given the country’s water users a false sense of water security and lack of appreciation, says Willem de Lange, environmental and resource economist at the CSIR. ‘The crux of the problem is distribution and cost. Potable water could become prohibitively expensive.’

That’s where the private sector has a key role to play. It needs to partner with government and municipalities to educate the public, and find water solutions that are cost-effective and sustainable.

The City of Cape Town recently asked for-profit and non-profit organisations to assist in building water resilience. In August, the city announced that within just one week of issuing tender specifications, more than 1 600 interested parties had downloaded the first of many requests for proposals (RFP) for procuring and commissioning various non-surface water augmentation schemes.

According to a media statement by the city: ‘The first RFP that has been issued pertains to land-based salt water reverse osmosis desalination plants. The proposed solutions included desalination at various scales (inclusive of container solutions, barges and ships); water re-use technology at various scales; aquifer and borehole options; engineering and infrastructure options; and water demand management options, among others.’

Cape Town is one of only a handful of African cities that have taken drastic methods to reduce water consumption. The mayor has not only warned some of the 55 000 highest water consumers in person through home visits or phone calls, but is considering ‘naming and shaming’ them in the media (the top 100 water wasters have already been publicly identified by street and suburb). They also have to pay steep penalties and their water supply will be cut off once they reach a monthly limit.

‘We are going after the excessive water users with a mass roll-out of the installation of water-management devices, which are being set at 350 litres per day per property,’ says De Lille. The water guzzlers are charged for these throttling devices, while poor households can apply for a free water-management device to help them comply with the water restrictions. The contractors who install and maintain the devices are selected via a tender process.

Other technologies to monitor and reduce water consumption include apps and smart water metres. In East Africa, the Kenyan firm KAPS introduced a smart metre solution for water utilities that provides real-time information on water supply and consumption. It also enables customers to log in, view analytical data of their water use and pay their bill online.

According to the company: ‘The system seeks to replace the current manual metre readings and billing system that has for a long time been inefficient, slow and mostly results in losses of data and coinage. To ensure simplicity, the system focuses on the three most important features – a collection of the data from the water source, the communication protocol through GPRS and reporting functionalities.’

At the southern tip of Africa, Stellenbosch University has developed an intelligent water-meter called Count Dropula and a monitor called Geasy, which is attached to a geyser and includes a SIM card and modem. It enables the geyser to be operated remotely (via a mobile phone app or PC) and can be programmed to send an SMS if the water consumption is too high or if there’s a leak.

‘We need to react quicker and smarter to adapt to water scarcity,’ says Kevin Winter, lecturer in environmental and geographical science and theme leader at the University of Cape Town’s Future Water Institute. He explains that the water value chain needs to be rethought completely. Domestic users in water-scarce areas, for instance, need to understand that they simply cannot use drinking water to wash cars, flush toilets, fill pools, irrigate gardens and hose down pavements.

South African company SewTreat has come up with a biological treatment that allows affluent and wastewater to be safely used for irrigation, flushing of toilets or general non-potable uses. ‘We treat nature with nature,’ says Theunis Coetzer, SewTreat MD. ‘The process involves confining naturally occurring bacteria at a very high concentration in the treatment process. Our approach is based on return activated sludge technology, incorporating submersed aeration media.

‘This enhanced bacterial action ensures a highly effective treatment process boasting a very low carbon footprint, minimal capital input and low maintenance requirements. In a nutshell, the bacteria digest all impurities and the wastewater is then cleansed,’ he says.

The company’s biological treatment plants have been popular with the hospitality sector, especially lodges in South Africa, Botswana, Ghana, Mozambique and Tanzania. Coetzer also sees potential for industrial, construction and mining operations across Africa.

By saving water through a combination of simple methods and high-tech solutions, water users in Africa can still adjust to the new normal. If everybody pulls together, day zero is not likely to arrive any time soon.