South Africa is a severely water-stressed country. With an average annual rainfall of 500 mm, compared to a global average of about 1 000 mm, it is currently one of the world’s driest nations. While some improvements in the provision of water-supply infrastructure have been achieved in the past two decades, things are nowhere near where they need to be. And, with continued population growth, increasing urbanisation and industrial development, the pressure on this infrastructure is mounting fast.

Compounding the problem is that much of the existing infrastructure is ageing, requiring maintenance, refurbishing or replacing. The latest report card published by the South African Institution of Civil Engineers in 2017 gave South Africa’s water infrastructure D– grades for both its bulk water infrastructure and non-urban water-supply facilities. The report indicated that infrastructure in these areas is poorly maintained, struggling to cope with demand and at serious risk of failure.

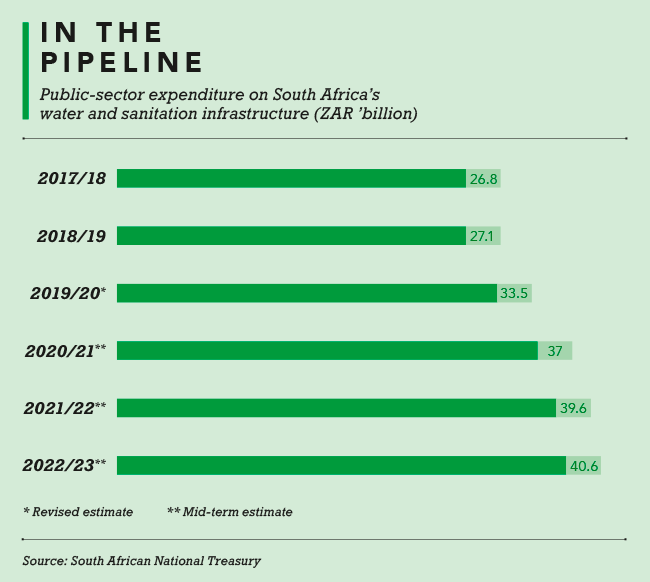

Thigesh Vather, assistant consultant: hydrology at WSP in Africa, calls the state of South Africa’s water infrastructure ‘worrying’. He adds that ‘South Africa’s water infrastructure has degraded over the years and although there has been investment in the water sector, the investment made is far less than the investment required’. The concern is that the country’s approach to water-infrastructure maintenance seems to be reactionary as opposed to preventative, which pushes up repair costs and reduces the lifespan of the infrastructure. That, coupled with a lack of engineering capacity, especially at municipal level where it is most needed, contributes to the mismanagement of the infrastructure and the inability to properly service it.

Mike Muller, adjunct professor from the University of the Witwatersrand School of Governance, argues that South Africa’s real water crisis lies in a lack of understanding of what’s needed. On the university’s website, Muller writes that ‘unhelpfully, there’s no single water problem, and the issues confronted vary widely from place to place’. He notes that while South Africa’s rainfall is unpredictable and variable, this has always been the case, and that reliable supplies can be provided to urban and industrial water users if storage infrastructure is built with enough capacity to cope with regular dry periods. ‘If the infrastructure needed is not developed when needed, problems will arise,’ he says. ‘And if water is drawn without restraint during a dry period, shortages will be the likely outcome.’

Across South Africa, various initiatives of differing size and scope are under way to respond to the gap in water-supply infrastructure. These projects vary from upgrades to existing infrastructure to the building of entirely new systems, and while some have experienced delays, others are right on track – and not a moment too soon.

The province of KwaZulu-Natal intends to spend ZAR30 billion over the next 10 years on two new dams, which will provide a combined 800 million litres of water a day. The biggest of the two is the Smithfield dam, located in the Upper uMkhomazi area and which is already under construction. It will contribute around 700 million litres a day to the province’s water supply. The second, Ngwadini dam, is set to begin construction in the 2020/21 financial year, adding 100 million litres per day. Umgeni Water CEO Thami Hlongwa says the two dams, together with the completion of the Hazelmere dam wall-expansion project, will secure the province’s water resources for the next 50 years.

Limpopo also has a busy few years ahead, with one new dam under construction, the ZAR4.6 billion Nwamitwa dam, due to be finished in 2026, and a wall-extension project currently under way on the Tzaneen dam. The Nwamitwa dam will be built downstream of the confluence of the Nwanedzi and Greater Letaba rivers and should have a storage capacity of 187 million m3. Work on the Tzaneen dam – which forms part of the Great Letaba River water development project, a ZAR2 billion initiative – includes raising the wall spillway by 3m, increasing the storage capacity by between 20% and 25%. The project hit some delays but is expected to be complete during the 2020/21 financial year.

Also under way in the province is Phase 2A of the Mokolo-Crocodile water-augmentation project, the capital cost of which is more than ZAR12 billion. The project will supplement water supplies to the Lephalale municipality, Eskom’s Matimba and Medupi power stations, and Exxaro’s Grootegeluk coal mine. The project is due for completion in May 2026.

In the Eastern Cape, the Umzimvubu is one of the largest rivers without a dam in South Africa, despite having a catchment of nearly 20 060 km2 and flowing more than 250 km. Feasibility studies on the possibility of a dam in this province, specifically to capture water from the Umzimvubu river and its key tributaries – the Tsitsa, Tina and Mzintlava rivers – were undertaken as far back as the early 1960s, so the untapped potential of this source is well known.

Bringing the Umzimvubu project to light requires developing two dams – the Ntabelanga and the Lalini – the former able to store approximately 490 million m3 of water and the latter 232 million m3. According to Human Settlements, Water and Sanitation Minister Lindiwe Sisulu, the project will be completed in stages, with the first phase now finally under way.

In the Western Cape, Clanwilliam dam, a concrete gravity dam on the Olifants river, is undergoing wall-raising. The massive project, costing around ZAR3.5 billion, will see the existing wall raised around 13m, doubling the dam’s capacity. The original walls were built in 1935, so the project will greatly improve the integrity of the structure. It is scheduled for completion in March 2023.

One of the largest projects is the second phase of the Lesotho Highlands Water Project (LHWP), the first phase having been completed in 2003. The LHWP is an ongoing partnership between the governments of South Africa and Lesotho, encompassing a system of several large dams and tunnels across Lesotho that deliver water to the Integrated Vaal River System (IVRS) in South Africa. The system comprises 14 dams with catchments in four provinces – Mpumalanga, Northern Cape, Free State and North West.

The second phase of the LHWP should have started delivering water to Gauteng last year, but the project is several years behind schedule, with construction beginning only recently. Phase 2 involves building two new dams (Polihali and Kobong), the Kobong pumped storage power station, and transfer tunnels into the existing Katse dam. Phase 2 will increase the current annual supply rate of 780 million m3 to more than 1.27 billion m3 a year. The new final completion date for Phase 2 is 2026.

Water-supply infrastructure challenges aside, there is also the matter of climate change. Some believe it will have a significant impact; others say not so much.

Vather believes that climate change will have a major bearing on the provision of water in South Africa. ‘Numerous climate models suggest that the eastern parts of South Africa will become wetter, while the western parts of South Africa will become drier,’ he says, adding that the provision of water will need to account for these changes. Water is also the primary medium through which society will feel the effects of climate change, argues Vather.

Muller says it is easy to blame climate change for water problems, although there is no certainty that climate change will dramatically reduce water supplies. ‘South Africa is not yet confronting an absolute water shortage. But the extent of public panic suggests a disturbing level of ignorance about how water is made available and what needs to be done to ensure adequate and reliable supplies,’ he writes. The key to ensuring water security is to better understand and manage the water resources we have, he adds, which goes for both government and citizens.

Then, there are also the economic impacts of the country’s flawed water-supply infrastructure to consider. Vather says there are ‘great implications’ if the challenges are not resolved. But, to solve them, a significant amount of capital, coupled with good governance, is needed – both of which are currently lacking in South Africa. ‘If the water infrastructure challenges are not resolved, the country will struggle to grow its economy,’ he says.

‘As the population increases, the demand for water increases. Therefore, the demand for water-supply infrastructure and sanitation infrastructure increases. A lack of adequate water-related infrastructure will result in health issues, which further affect the economy. The impacts of climate change will also affect the agricultural sector and will likely affect food security.’

In short, as water becomes scarcer, so the need to treat increasingly polluted water to make it usable becomes more urgent, also requiring a lot of energy and leading to more emissions, he continues. ‘Therefore, to secure a positive economic outlook, the water infrastructure challenges need to be resolved.’

By Toni Muir

Images: Gallo/Getty Images