Two hundred and seventeen years – that’s how long the World Economic Forum’s 2017 Global Gender Gap Report predicted it will take for economic equality to be achieved globally between the sexes, based on current trends and the continued widening of the economic gender gap. ‘Globally, gender parity is shifting into reverse this year for the first time since the World Economic Forum started measuring it in 2006,’ says WEF founder Klaus Schwab. Of the 106 countries covered by the report since its inception, sub-Saharan Africa was predicted to close the gender gap in 102 years, ahead of Eastern Europe, Central Asia, the Middle East, North Africa and North America.

‘A variety of models and empirical studies have suggested that improving gender parity may result in significant economic dividends,’ says the report. ‘Notable recent estimates suggest that economic gender parity could add an additional US$250 billion to the GDP of the United Kingdom, US$1,750 billion to that of the United States, US$550 billion to Japan’s, US$320 billion to France’s and US$310 billion to the GDP of Germany. Other recent estimates suggest that China could see a US$2.5 trillion GDP increase from gender parity and that the world as a whole could increase global GDP by US$5.3 trillion by 2025 by closing the gender gap in economic participation by 25% over the same period.’

Which begs the question: do the world’s corporate and political elite (vastly male), even read these reports? Do South Africa’s? Let’s say, for argument’s sake, that entrenched sexism is at the heart of the matter… Surely the prospect of increased profit – cold hard cash – would sway the decision in women’s favour? Do we really have to wait one hundred years, perhaps two, before women have access to the same economic opportunities as men?

On average, the 144 countries covered in the report have closed 96% of the gap in health outcomes between women and men, unchanged since 2016, and more than 95% of the gap in educational attainment, a slight decrease compared to last year. However, the gaps between women and men on economic participation and political empowerment remain wide: only 58% of the economic participation gap has been closed – a second consecutive year of reversed progress and the lowest value measured by the Index since 2008 – and about 23% of the political gap, unchanged since last year against a long-term trend of slow but steady improvement.

So where does South Africa lie in this scenario? It scores big on political equality, average on education, but low on economic empowerment and health-and-survival, ranking 79th for the former and 59th for the latter.

The official rate of unemployment among women was 29.5% in the second quarter of 2018 compared with 25.3% among men, according to a report on gender by Statistics South Africa. According to the expanded definition of unemployment, there is an even bigger difference – 7.5 percentage points. ‘Women accounted for 43.8% of total employment in the second quarter of 2018. Only 32% of managers in South Africa were women. Females dominated the domestic worker and clerk or technician occupations, with men dominating the rest. Only 3% of domestic worker jobs were occupied by men while 10.9% of craft and related trade jobs were occupied by women.’

The report concludes that the labour market position of women hasn’t changed much over the past decade – and has, in fact, deteriorated in some respects, echoing the findings of the WEF report.

‘JSE-listed companies control about 90% of the South African economy,’ according to Kerry Oosthuizen, Businesswomen’s Association of South Africa (BWASA) board member and an adviser at the Commission for Gender Equality. ‘The 2017 BWASA Women in Leadership census study looked at 277 JSE-listed companies and once again found a dearth of gender diversity. Only 4.7% had female chief executives, 6.9% had women chairpersons, 19.1% had female directors and 29.5% had female executive managers.’

It would appear there is a lack of will on the part of corporates to support and empower women as entrepreneurs, managers, executives and leaders to close the inequality gap. Is that true?

‘There is support out there for women in business, but it seems thin on the ground and lacking in focus,’ says Yvonne Wakefield, founder and CEO of law consultancy Caveat Legal and one of 15 qualifiers for Ernst & Young South Africa’s Entrepreneurial Winning Women programme, which works with women entrepreneurs whose businesses show potential for growth. This year, 15 women business owners will take part in the programme.

‘It’s not business skills that women need,’ says Wakefield. ‘I believe that the vast majority of women are naturally entrepreneurial and have at least the street smarts to run an undertaking in the early stages. It’s access to market that women entrepreneurs need help with. Access to market brings greater revenues, which in turn enables women leaders to develop their skills or hire specialists where necessary. This is where the focus needs to be.’

This year the theme of the programme is #Pressforprogress. It exposes participants to entrepreneurs, investors and advisers who can help them – a business network of the country’s best high-growth companies. It sounds like the kind of thing corporate South Africa needs more of – much more. Which other businesses are taking action?

Winner of Trialogue’s 2017 Strategic CSI Award (and a slew of others over the years), Mama Afrika is a project by dairy brand Clover that rewards entrepreneurial women who have taken the initiative and already made a significant impact on their community by empowering others and boosting economic agency. ‘These women are trained with skills such as cooking, baking, sewing, crafts, haircare, welding, food gardening and business and financial management,’ reports Trialogue (a consultancy that focuses exclusively on corporate responsibility issues), ‘and are then required to pass these skills onto others in their communities. They also receive the necessary equipment and infrastructure to create local industry centres, based on their honed skills. When comparing the investment in Clover Mama Afrika since the project’s inception, to the income that project participants have generated, return on investment stands at 116%.’

Earlier this year, education accreditation body the South African Institute of Learning (SAIL) announced the launch of its 1956 Women’s Business Empowerment Programme, named in honour of the Women’s March to the Union Buildings that year. Qualifying SMEs will receive development training worth R5.6 million. ‘The programme will cover entrepreneurship, communication skills, leadership development, business plans, finances and budgeting, understanding operational requirements, innovation, marketing and customer service,’ says SAIL founder and MD Vimala Ariyan.

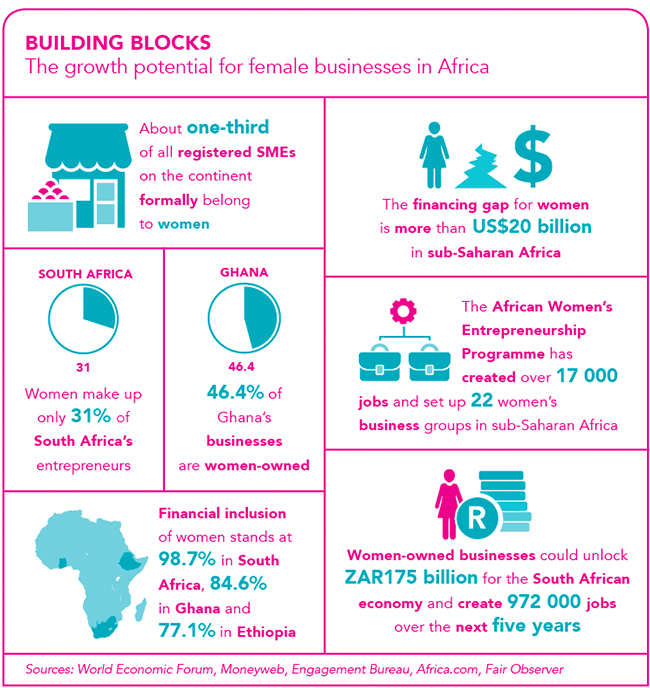

‘Small businesses play a crucial role in the economy: they provide employment and competition, a few innovate and grow into businesses of scale and sophistication and, importantly, in the South African context they help reduce an over-concentration of economic power. Unemployment is one of the greatest challenges facing people in our country – particularly women. Therefore, there is a pressing need to develop and grow SMEs run by women as they play an important role in the South African economy.’

Cell C’s Take a Girl Child to Work Day is in its 16th year and has touched the lives of over a million South African girls. An extension of this is the Cell C Girl Child Bursary Fund, established in 2013, which invests in the tertiary education of disadvantaged young women (helping them to qualify in the fields of law, IT and commerce, among others). The fund has delivered 12 female graduates – all of whom are successfully employed.

Soft drink megabrand Coca-Cola has an interesting global project called #5by20, which supports women micro-entrepreneurs – the goal being to economically empower 5 million women entrepreneurs across its value chain by 2020. According to BusinessWire, in 2013 Coca-Cola and Ipsos, a leading global market research company, began conducting an impact study of 101 women entrepreneurs in the Gauteng and North West provinces. ‘These women retailers were part of a larger 5by20 business skills training programme implemented in collaboration with partners UN Women and Hand in Hand Southern Africa. Results collected over 18 months indicate that, on average, women entrepreneurs participating in the study saw increases in sales and personal income, which they were able to use for basic expenses for their families and to put into savings accounts.’

Over the past eight years, more than a million women entrepreneurs have been assisted by the programme in Africa.

In the construction sector, the National Home Builders Registration Council (NHBRC) is investing in emerging female entrepreneurs through its Women in Construction Programme by supporting them to attend a business development programme at the Gordon Institute of Business Science (GIBS). At least 20 women have benefited from the programme, and last year the NHBRC honoured 100 ‘trailblazing women in construction’ at the GIBS graduation ceremony for the programme, providing invaluable networking and mentorship opportunities to participants.

There is also much companies can do within their ranks to boost equality. Rand Merchant Bank’s Lotus Programme was established in 2016 with 40 women in that year and 60 females in 2017, to encourage women to grow as natural leaders through networking and development opportunities. This grew out of the institution’s trailblazing equality project Athena, founded by the bank’s Jessica Spira, created to attract more women to the banking sector and leadership positions – and generally initiate important conversations around gender and diversity.

These are some of the most focused corporate enterprises geared towards economic equality, and their impact for the women involved is no doubt significant. This, however, is a relative drop in the ocean of need for support and empowerment by female entrepreneurs and businesswomen. Not only is it imperative for the economy that the gender gap between men and women is bridged – this is also a humanitarian issue. Women who are economically empowered not only make their countries richer, they are also able to better provide for the next generation, they are less likely to experience abuse and – obviously – less likely to live in poverty.

‘As the world moves from capitalism into the era of talentism,’ says Klaus Schwab in the WEF gender report, ‘competitiveness on a national and on a business level will be decided more than ever before by the innovative capacity of a country or a company. In this new context, the integration of women into the talent pool becomes a must.’