The election of Angolan President João Lourenço in 2017 raised hopes of a shift from the authoritarian and corrupt era of his predecessor. This was thanks to the new, more open and approachable style of governance he instituted in his first months in office. This included opening up the public media as well as symbolic gestures such as ending the practice of blocking off road traffic for the president’s motorcade to pass.

Yet ahead of the August 2022 elections, in which Lourenço is running for a second term, these hopes have largely been dashed.

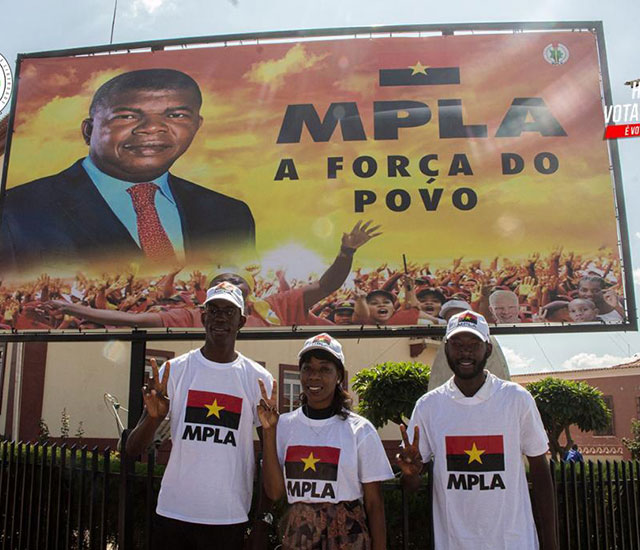

Lourenço’s moves to ‘open up’ the Angolan economy have had little effect. Instead, an economic crisis that has endured since late 2014 has led to popular dissatisfaction and anger among Angolans. This anger is behind the formation of a broad political opposition front against the ruling party, the People’s Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA). The new United Patriotic Front brings together key opposition leaders as well as civil society organisations.

This front could be the best hope for opposition and civil society activists to prevent yet another victory for the MPLA and João Lourenço. That’s because it brings together under one umbrella key opposition leaders and offers a credible alternative for those disaffected with Lourenço and his party.

That said, even though the ruling party’s voter share has been steadily declining, it is likely to win again with more than 50% of the vote due to electoral fraud and obstruction.

To quell potential threats to its continued dominance Lourenço’s party – which has ruled Angola since independence in 1975 —- is using all instruments at its disposal to hobble the opposition.

Finished and unfinished business

Former president José Eduardo dos Santos stepped back ahead of the 2017 elections after 38 years in power. Lourenço, the MPLA’s new candidate for the presidency, was widely panned as an uninspiring party soldier and Dos Santos loyalist. Campaigning under the slogan, “improve what is good, correct what is bad”, Lourenço promised more of the same, just perhaps slightly better.

Yet he managed to surprise many by unleashing a flurry of dismissals of high-ranking government officials and civil servants.

The fight against corruption was his first major policy plank. This has been selectively successful. For example, he instituted high-profile corruption inquiries. These included several investigations into the dealings of the dos Santos family itself.

This earned him the praise of critics and citizens. And it was a crucial element towards his other main priority, which was to reposition Angola as a trustworthy partner on the global stage. The negotiation of an agreement with the International Monetary Fund for a multibillion credit line to stabilise the ailing economy in 2018, was trumpeted as evidence of Angola’s openness to reform.

The change paved the way for new oil investments and some debt rescheduling.

Yet these ‘reforms’ have largely been geared towards external audiences – including regaining the trust of foreign investors.

Rather than improving socio-economic circumstances, self-inflicted austerity measures have hit the poorer parts of the population hardest. Debt servicing stands at 60% of government expenditure. Health and education are languishing at levels of spending that are among the continent’s lowest. And service standards are just as low.

The cost of living has skyrocketed, with the price of basic foodstuffs exploding.

Opposition consolidates

A newly invigorated opposition is promising to capitalise on rising popular dissatisfaction. This has resulted in frequent strikes and protests across the country.

The opposition has never been in a better position to earn the vote of Angolans. In an initial phase (2017-19) the Angolan public was willing to trust the new president’s willingness to reform. Since then, the socio-economic situation has got worse.

Many citizens (including some within the MPLA) are dissatisfied with a selective fight against corruption that targets Dos Santos’ allies while promoting oligopolies associated with Lourenço.

The end of the honeymoon coincided with change at the head of the opposition National Union for the Total Independence of Angola (UNITA ), one of Angola’s three historic liberation movements turned rebel group turned opposition party, which elected Adalberto Costa Júnior in November 2019. He was, until his election to the party presidency, the head of the party’s parliamentary bench. He’s a fierce critic of the MPLA and its anti-corruption policies.

Costa Júnior (60) quickly gained in popularity, articulating clear positions and cutting a much more presidential figure than his predecessor, Isaías Samakuva.

Costa Júnior’s ascendance also paved the way for the creation of the United Patriotic Front.

The front includes large sectors of organised civil society opposed to the MPLA as well as political parties. These include UNITA, the Bloco Democrático of Filomeno Vieira Lopes and the political project Pra-Já servir Angola, of Abel Chivukuvuku (ex-UNITA and ex-CASA-CE).

The empire strikes back

A politicised judiciary is playing a key role in Lourenço’s fight back.

Rattled by the threat posed by Costa Júnior, Lourenço has mobilised the Constitutional Court, where most of the judges are associated with the MPLA.

After a bogus claim by some alleged UNITA member, the court in October 2021 annulled the party’s 13th congress held in 2019 that had elected Costa Júnior as leader on spurious grounds.

This was a political rather than a legal decision, with a majority of judges following the wishes of the president. The ruling triggered angry protests across the country.

An extraordinary UNITA party congress in December 2021 reelected Costa Júnior with an overwhelming majority. But a further six-month delay by the court in validating that second congress (plus those of five other parties) tied UNITA up in exhausting legal challenges. This prolonged insecurity and impeded Costa Júnior from pre-election campaigning or signing any agreements in the name of the party.

Looking forward

Three months ahead of elections, Angola presents a paradoxical picture. While foreign investors hail Lourenço as a “courageous” great reformer, hunger, poverty, and popular dissatisfaction are on the rise.

The MPLA is reverting to old authoritarian reflexes – legal-administrative obstacles, harassment and intimidation, physical violence, arbitrary detention, extra-legal killings, media manipulation, judicial bias and electoral fraud – to thwart any possible opposition threat to its dominance.

The United Patriotic Front faces likely legal challenges, voter registration is marred by obstacles, human rights violations and the repression of protests are on the rise again. State-controlled media give overwhelming airtime to the MPLA while censoring opposition voices.

As a result, the elections are likely to be marred by fraud, intimidation and violence, with a subservient judiciary again quashing any legal challenges to the MPLA.![]()

Jon Schubert, SNF Eccellenza Professor, University of Basel and Gilson Lázaro, Associate professor, Catholic University of Angola

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Follow African Insider on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram

Source: The Conversation

Picture: Pixabay

For more African news, visit Africaninsider.com