Jane Duncan, University of Johannesburg

South Africa’s judicial probe into state capture and corruption, the Zondo Commission, has concluded that the State Security Agency was integral to the capture of the state by corrupt elements. These included former president Jacob Zuma’s friends, the Gupta family.

The agency has been unstable for some time. Previous investigations have made findings to improve the performance of civilian intelligence. Yet problems relating to poor performance and politicisation persist. They escalated during Zuma’s tenure.

The commission’s hearings were remarkable for an institution that had become used to operating secretly. Spies testified in detail, and in public, about what had gone wrong at the agency during the Zuma era (May 2014 to February 2018). Some did so at great personal risk.

I have researched intelligence and surveillance, and served on the High Level Review Panel on the State Security Agency. In my view, the Zondo report is a globally significant example of radical transparency around intelligence abuses. But it lacks the detailed findings and recommendations to enable speedy prosecutions. It also fails to address the broader threats to democracy posed by unaccountable intelligence.

Covert operations

The commission heard evidence pointing to fraud, corruption and abuse of taxpayers’ money at the agency. It also heard how the Guptas benefited from these abuses. The agency shielded them from investigations that indicated they were a national security threat.

The most significant recommendation is that law enforcement agencies should further investigate whether people implicated in the report committed crimes. The commission expressed particular concern about covert intelligence projects that appeared to be “special purpose vehicles to siphon funds”. It made specific reference to three people who should be investigated further.

The first is former director-general Arthur Fraser, for his involvement in the Principal Agent Network. This was a covert intelligence collection entity outside the State Security Agency. It has been controversial for over a decade after investigations pointed to the abuse of funds.

The second person is former deputy director-general of counter-intelligence Thulani Dlomo. He was responsible for the Chief Directorate Special Operations, a covert structure which the report says ran irregular projects and operations that could well have been unlawful.

The most significant of these was Project Mayibuye, a collection of operations designed to counter threats to state authority. In practice, they and others sought to shield Zuma from a growing chorus of criticism of his misrule.

The commission found that the project destabilised opposition parties and benefited the Zuma faction in the ruling African National Congress.

The third person is the former minister of state security, David Mahlobo. The commission found that he became involved in operational matters instead of confining himself to executive oversight. It also found that his handling of large amounts of cash, ostensibly to fund operations, needed further investigation.

According to the commission, Mahlobo’s predecessor, Siyabonga Cwele, did the same by stopping an investigation into the Guptas and their influence on Zuma’s administration.

The commission concluded, based on overwhelming evidence, that Zuma and Cwele did not want the investigation to continue. Had it continued, it could have prevented at least some of the activities that led to the capture of the state by the Guptas and the loss of billions in public money through corruption.

Recipe for abuse

The commission also addressed some of the deeper factors that predisposed the State Security Agency to abuse.

One of these was the amalgamation of the domestic intelligence branch, the National Intelligence Agency, with the foreign branch, the South African Secret Service, into a new entity, the State Security Agency, in 2009.

The commission found that the amalgamation had disastrous consequences, as it allowed most of the abuses it examined to happen. The two entities were merged in terms of a presidential proclamation. Yet the constitution requires intelligence services to be established through legislation. This meant that until legislation was introduced in 2013, the security agency operated without a clear legal basis.

It was highly centralised, allowing a super-director-general to control all activities. This made abuse easier for an appointee with corrupt intentions. The agency was also based on a state security doctrine, rather than a people-centred doctrine. This doctrinal shift prioritised the protection of the state from criticism, and the president more specifically, rather than the security of society. Ministerial political overreach into operational matters heightened the potential for abuse.

The commission also found that the Joint Standing Committee on Intelligence, the Inspector General of Intelligence and the Auditor General had failed to exercise proper oversight. This meant the external checks and balances on the State Security Agency were weak to non-existent.

Weighing the Zondo report

The struggle for more accountable intelligence has been strengthened through the Zondo report’s exposure of abuses. But many of the findings and recommendations are vague and general. The commission could have been more specific about upgrading the Inspector General’s independence, for instance. Likwewise the Auditor General’s capacity to audit the agency.

The commission could also have made more of the evidence presented to it. And it could have been more categorical about when it thought criminality had occurred. At times, the report does little more than restate the recommendations of previous enquiries.

These include an investigation into the Principal Agent Network programme in 2009, providing prima facie evidence of criminality.

Another is the report of the 2018 High Level Review Panel, which showed that the agency had been politicised and repurposed to benefit Zuma.

An important gap in the Zondo report relates to the infiltration and surveillance of civil society, and the agency’s broader threat to democracy.

Little is made of the fact that, according to a recently 2017 declassified performance report, the agency claimed to have infiltrated Greenpeace Africa, the Right2Know Campaign, trade unions and other civil society organs.

The spies masqueraded as activists. They reported back to the agency on supporter strengths, main actors, ideology, support structures and agendas. The report’s author, a security agency member, boasted about these and other accomplishments, such as infiltrating the social media networks of the Western Cape #feesmustfall student movement.

Looking ahead

In the preparations to investigate and prosecute wrongdoers responsible for the abuses by the State Security Agency, its infiltration of civil society must not be allowed to fall under the radar. It must receive as much attention as all the cases of grand corruption that are going to keep the National Prosecuting Authority busy.

Otherwise, the social forces that could potentially bring deeper and more meaningful changes to society may remain targets of state spying, as has been the case elsewhere.![]()

Jane Duncan, Professor, Department of Communication and Media, University of Johannesburg

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Follow African Insider on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram

Source: The Convesration

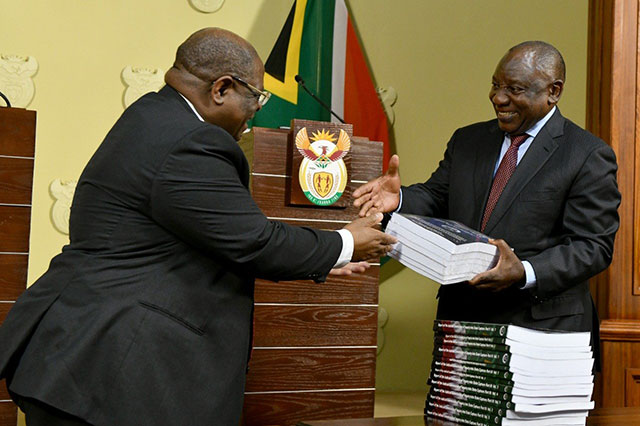

Picture: Twitter/@GovernmentZA

For more African news, visit Africaninsider.com