Moses B. Khanyile, Stellenbosch University

The recent furore over accusations by the US ambassador to South Africa, Reuben Brigety, that South Africa was supplying arms to Russia despite its declared policy of non-alignment, has sparked a debate on whether the country’s arms control is lax, non-compliant and lacks oversight.

The debate was further fuelled by the South African government’s reluctance to provide clear answers to questions about what Russia’s Lady R cargo ship came to deliver – or to pick up – from South Africa in December 2022.

The general view about arms transactions is that they are always shrouded in secrecy. And that they involve some of the most unscrupulous characters. But, in my view, based on my expertise in defence policy, intelligence and international security, these are misconceptions. The South African defence industry is one of the most highly regulated in the world. That’s not to say it isn’t prone to manipulation and weaponisation for foreign policy objectives.

Allegations of flouting international arms control rules, let alone being party to the Russia-Ukraine conflict, place the South African defence industry in a precarious position globally. It is vulnerable to the loss of preferential trade relations. Existing and future contracts are jeopardised.

Companies and people found to have flouted the arms control legislation would be prosecuted in the South African courts. They would also most likely face sanctions from some western countries, including the US.

The Lady R incident has compromised South Africa’s credibility as a compliant state when it comes to arms control. There may be much more scrutiny for future transactions. Given South Africa’s insistence on non-alignment and neutrality, such allegations cast doubt on its status as a credible peace broker. However, two developments will go a long way towards alleviating the impact of the allegations.

The first is the announcement by South African president Cyril Ramaphosa that a new effort involving six African countries has been initiated

to explore an end to the year-long Russia-Ukraine war. The second is Ramaphosa’s announcement that there will be a judicial inquiry into the US ambassador’s allegation.

Arms control: what’s in place

South Africa has arguably some of the most stringent governance frameworks for arms control on international trade. The regulations and laws it has in place cover conventional arms, non-proliferation of nuclear, biological, and chemical weapon materials and dual-use goods and services.

It is this strictness that has sometimes caused discomfort with the South African defence industry. There have been complaints from the industry that some lucrative prospective transactions have been lost because they’ve been declined by the National Conventional Arms Control Committeee, or delayed by calls for more scrutiny.

South Africa’s National Conventional Arms Control Committee and the Non-Proliferation Council have been set up under laws governing arms control as the final decision-making bodies on international arms transfers. Given the conventional nature of the ongoing Russia-Ukraine conflict, it would appear the suspected weapons transaction with Russia would be within the purview of National Conventional Arms Control Committee.

Public and private sector involvement

What seems to have irritated the South African government and confused the public in the US ambassador’s accusatory statement is the inherent assumption that all arms transactions are conducted by the state. This is incorrect.

Even though the National Conventional Arms Control Committee decides on whether a particular arms transaction should proceed, it does not manage the fulfilment of the transaction. This includes the logistical arrangements. The onus lies with the relevant company to conclude the transaction in line with the provisions of the permit and the associated end-user certificate.

The South African defence industry comprises state-owned entities such as Denel, Armscor and a division of the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research and private companies. Armscor, as the government’s acquisition agency, has its own logistical capability called AB Logistics. It is authorised to move sensitive, controlled, and hazardous military goods in support of the South African National Defence Force, South African defence industry companies and, in some cases, for foreign clients.

The defence force itself is not mandated to engage in arms transactions except through Armscor.

What this shows is that the investigation into the allegations of arms supply to Russia would involve public and private role-players.

Further compounding matters is the fact that the Lady R cargo ship docked at the time when Russia was preparing for participation in the joint military exercise with China and South Africa (Ex Morsi II) which took place in February 2023. It is not clear if its arrival was linked to the joint military exercise, which would be easy for government to clarify. Regrettably, this coincided with the first anniversary of Russia’s attack on Ukraine.

Who sells what to whom

Russia is a significant arms supplier to the African continent with 49% of the market share. But the arms transfers between Russia and South Africa have been insignificant by volume, value and even firepower. The same applies to the US.

Both Russia and the US are self-sufficient and, together with South Africa, they are competitors in the global arms marketplace. In addition, most of South Africa’s export arms equipment and ammunition is aligned with NATO standards, which are not necessarily compatible with the Russian equipment.

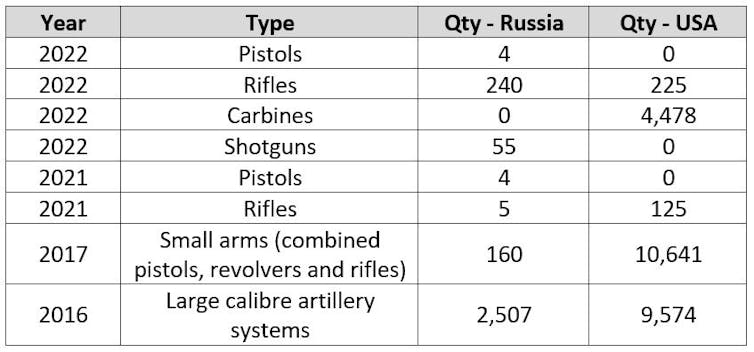

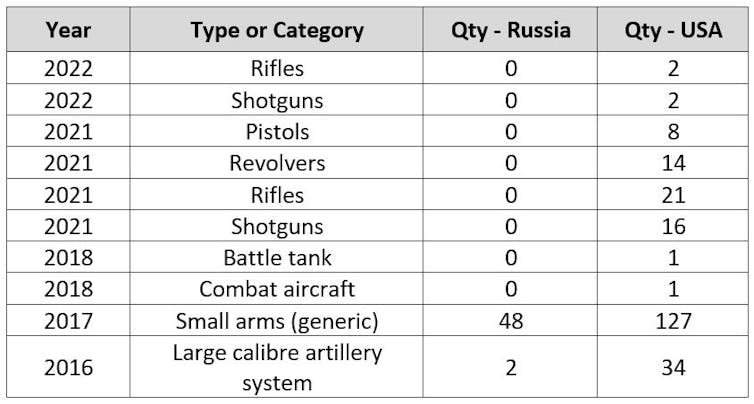

The figures in Table 1 and Table 2 set out the nature and size of arms transactions. They provide context to the US ambassador’s allegations.

Source: https://www.unroca.org/

As Table 1 shows, South Africa’s arms imports from both countries were largely in the small arms category from 2017 to 2022. It was only in 2016 that large calibre artillery systems (Category III) were ordered in significant numbers. There were no arms transactions reported for 2018, 2019 and 2020.

Source: https://www.unroca.org/

Similarly, from the export perspective, South Africa exported a negligible amount of small arms from 2016 to 2022. There were no export transactions for 2019 and 2020.

Potential focus areas for the inquiry

Establishing the factual basis of the allegations is the primary mandate of the judicial inquiry. The actual contents of the consignment of Lady R, and the direction of the transaction (incoming or outgoing cargo or both) will need to be crucial elements of the inquiry.

The legitimacy of the transaction in terms of legislative compliance, including documentary evidence, should enjoy priority. This will be linked to the institutions and the personnel involved in the preparation, processing and finalisation of the transaction. This would need to be done before concluding whether the transaction could be directly or indirectly linked to Russia-Ukraine conflict.

The terms of reference for the inquiry will clearly give an indication of the scope and depth of issues to be investigated. And the associated options for consequence management.

What next

Regardless of the outcome of the inquiry, more efforts will have to be made to repair diplomatic relations between South Africa and its western economic partners.

The ultimate goal will be to restore diplomatic status as it was before and to avert the potential exclusion of South Africa from the Africa Growth and Opportunity Act benefits. This should be accompanied by measures to prevent the repeat of public outbursts that defy diplomatic protocols.![]()

Moses B. Khanyile, Director: Centre for Military Studies, Faculty of Military Science, Stellenbosch University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Follow African Insider on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram

Source: The Conversation

Picture: Twitter/@PresidencyZA

For more African news, visit Africaninsider.com