Good corporate governance means persistently doing the right thing – even when no one is looking. It’s at the core of anything that goes right and wrong in business, and as such remains critical to Africa’s economic future – in both good and bad times.

So if something does go wrong – for example, the banking scandal in Kenya a few years ago or the deadly listeria outbreak that is being linked to a listed company in South Africa – organisations’ responses need to follow the basic principles of corporate governance: responsibility, accountability, transparency, integrity, competence and fairness. In other words, the company leadership should own up to the matter and suggest a way of solving or mitigating it instead of covering it up or blaming someone else.

Those who participate in corporate ‘shenanigans’ should be brought to book, and either demoted or dismissed, depending on the seriousness of their wrongdoing, according to Deon Rossouw, CEO of the Ethics Institute. ‘It starts with leadership, certainly, but the hard work – embedding ethical standards, getting the team right and reinforcing through consequences – will determine the extent to which those leaders’ hopes of restoring organisational integrity can be achieved,’ he wrote in an opinion piece. ‘It is not only the ethical tone at the top that matters, but also the ethical mood in the middle, and the ethical groundswell on the ground.’

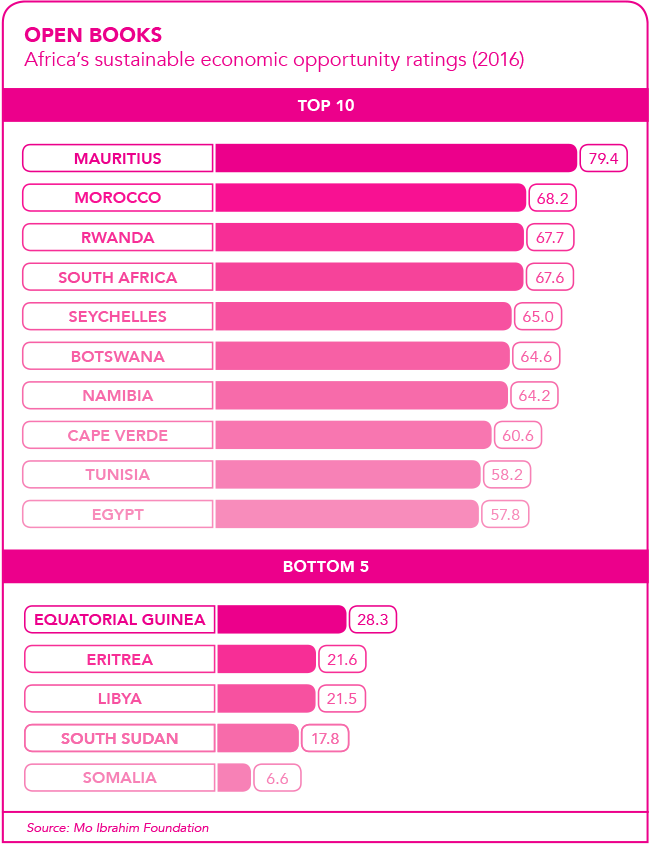

Luckily, the appreciation of business ethics and sustainability seems to be growing across the continent – despite the startling number of African companies involved in corporate governance failures. ‘We found that sound governance practices and guidelines enhance investor confidence, and help the growth of globally relevant and competitive firms,’ says Shameela Soobramoney, senior manager: group strategy and sustainability at the JSE.

Here governance frameworks (such as the King Code on Good Governance, the International Integrated Reporting Framework, the UN Global Compact or the Equator Principles for responsible banking) provide a useful set of guidelines for entities and their governing bodies. According to Soobramoney, such frameworks assist organisations – regard-less of their profit motive or mission; whether they are public, private, state-owned or non-profit – in embedding sound governance practices both in their day-to-day operations as well as in the formulation of their strategies.

While South Africa’s voluntary private sector-issued King IV is regarded as one of the best in the world, other African countries including Mauritius, Malawi and Zimbabwe have developed national codes of corporate governance.

In Nigeria, the Financial Reporting Council appointed a technical committee in February 2018 to review the country’s first National Code of Corporate Governance. Media reports stated that government had suspended the legislation shortly after its release in October 2016, ‘following controversies surrounding some sections of the code’.

In Kenya, listed companies now have to comply with the country’s Code of Corporate Governance Practices (based on the ‘apply or explain’ principle), which came into effect in March 2017.

A 2016 survey on the State of Corporate Governance in Africa in 13 African countries found that ‘discussions of development and implementation of corporate governance frameworks are very much “alive and well” across the country-level and African regional economies, from the more sophisticated to the least developed economies’.

The African Corporate Governance Network (ACGN) commissioned EY to publish the survey as a baseline showing what research and information on this issue is available in Egypt, Ghana, Kenya, Malawi, Mauritius, Mozambique, Nigeria, South Africa, Tanzania, Tunisia, Uganda, Zambia and Zimbabwe.

The research revealed that while some countries were ‘new adopters’ compared to those that already had an established history of development of corporate governance, they all shared one key aspect: ‘All of these countries have established an institute of directors or institutes of corporate governance as part of furthering their corporate governance development journey. These institutes play a key role, and sometimes even a leading role, in pushing the boundaries of corporate governance development forward in order to remain aligned with achieving the country’s contemporary economic and social agendas.’

The Institute of Directors in Southern Africa (IoDSA) – which together with its counterpart from Mauritius initiated the formation of the ACGN in 2013 – is a trailblazer in this arena. One of its key roles is the custodianship of the King Reports, which includes keeping all stakeholders informed of the latest governance developments and initiatives. Parmi Natesan, executive: Centre for Corporate Governance at IoDSA, emphasises that the voluntary King IV framework (released in November 2016) must not be seen as a compliance burden but as a critical tool for building successful, sustainable organisations.

‘In King IV we say that corporate governance is essentially about ethical and effective leadership. So there is no point in implementing a governance code that results in people just ticking boxes – applying practices for the sake of applying them. This needs to result in something. More awareness around the true meaning of governance is essential.’

She explains that the new outcomes-based approach is easier to implement in different types of organisation than the approach of the previous reports, because it’s fundamentally about the right mindset and culture. ‘When an ethical mindset is present, individuals and companies will seek to act in the right way, even when nobody is looking, because they understand that to do so makes good business sense and reduces risk.’

And while other African countries can ‘certainly borrow’ from the concepts of King IV, Natesan cautions: ‘As every country is different, a simple copy and paste would not be advisable. It would need some application of mind to tailor a governance code that is suitable to each country and their unique needs at a point in time.’

Soobramoney agrees: ‘Every market needs to consider what is relevant for their context in relation to any other laws that guide companies on such matters. The basics of good governance apply universally.’ She underlines the importance of knowledge sharing and explains that the JSE offers training programmes on governance, ethics and sustainability, which are open to all interested parties and can be customised and held at a location suitable to participants.

‘We are members of various regional exchange-focused bodies where we both learn from and provide support to our African peers,’ says Soobramoney. ‘Entities such as the African Securities Exchanges Association and the Committee of the SADC Stock Exchanges, of which the JSE is a part, are platforms for engagement and knowledge sharing with the purpose of enhancing exchanges and markets on the continent.

‘We are also a founding member of the Sustainable Stock Exchanges Initiative [SSEI], which is a global peer-to-peer learning platform for exploring how exchanges – in collaboration with investors, regulators, and companies – can enhance corporate transparency and ultimately performance on environmental, social and governance issues and encourage sustainable investment.’ The SSEI incorporates a further 14 African exchanges, which are all working towards embedding sustainability in their markets.

However, while stock exchanges can promote corporate governance through their listing requirements and stringent controls, they are only one of numerous players providing oversight of listed companies. ‘The JSE forms part of an ecosystem of different institutions who each need to play their part for companies to be subjected to adequate and healthy levels of scrutiny. This ecosystem includes auditors, shareholders, board members, investment analysts, sector specific regulators and even the media,’ says Soobramoney.

The IoDSA advises companies to implement a zero-tolerance policy against corruption, safe whistle-blowing facilities and strong board committees dealing with social and ethics issues, audit and risk, as well as remuneration.

However, those wanting to circumvent the law will always find ways, and there’s not enough manpower to have eyes on everything. That’s why people need to understand a simple logic, says CFO of the multinational Raiffeisen Bank, Martin Grüll. ‘No transparency, no trust. No trust, no credit. No credit, no investment. No investment, no growth.’

It’s therefore clear that Africa needs stronger corporate governance to attract economic growth. Ultimately it’s in the personal interest of every single business leader to act with integrity and transparency, in a responsible, accountable, competent and fair manner – especially when nobody is watching.