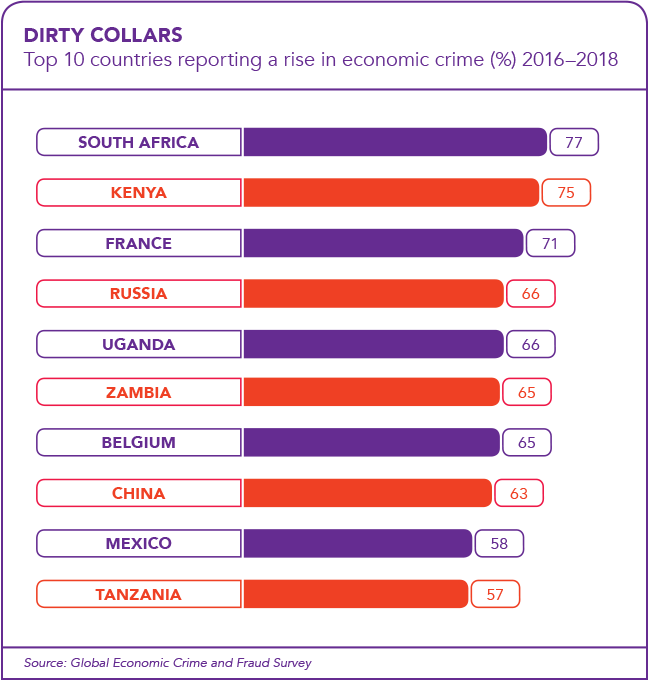

There are no blood-stained crime scenes, no victims with visible injuries in white-collar crime. Their perpetrators are not rough-and-ready looking criminals; instead they often hold high-ranking positions in the economy and politics. Perhaps surprisingly, such ‘crimes in the suites’ can cause the same or more harm to an economy than ‘crimes on the streets’.

Recent corporate scandals in Southern Africa have demonstrated that when organisations fail, the economy takes a knock. Strong legal and regulatory frameworks are crucial to reduce the prevalence of white-collar crime. According to the PwC Global Economic Crime and Fraud Survey 2018, ‘asset appropriation’ remains the most common economic crime in South Africa, followed by ‘fraud committed by consumers’, ‘procurement fraud’, ‘bribery and corruption’ and ‘business misconduct’. The survey notes: ‘Every category of economic crime types showed diminished instances of occurrence in comparison to 2016, with two exceptions: instances of accounting fraud increased to 22% (2016: 20%) and those of competition/anti-trust law infringements increased to 3% (2016: 1%).

The ranking also features cybercrime, HR fraud, money laundering, intellectual property theft, insider trading and tax fraud. All of these seemingly ‘victimless’ wrongdoings cripple the economy (PwC reports that 19% of organisations have had to spend between twice and 10 times as much on investigations as the original amount lost to economic crime).

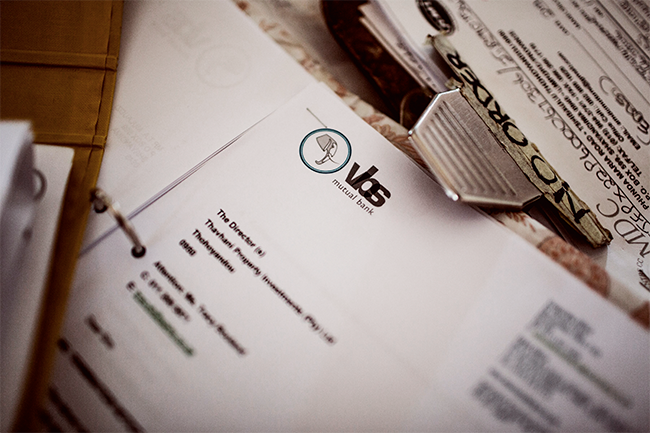

The most vulnerable members of society also suffer, as demonstrated in the VBS Mutual Bank collapse, where rural clients were cheated out of their life savings. Residents of Limpopo had their electricity and water supply cut off when their municipalities couldn’t pay after (illegally) investing in the corrupt bank.

‘We have seen from the global financial crisis how far-reaching the negative consequences of an unstable financial system can be,’ says Liezl Groenewald, senior manager of organisational ethics at the Ethics Institute, and president of the Business Ethics Network of Africa. ‘Effective and strong regulation of financial authorities not only maintains the integrity of financial systems, but is crucial to economic growth, financial stability and job creation,’ she says. ‘Regulations are also important to protect customers and taxpayers from moral hazards, such as fraud and irresponsible lending practices, that are inherent to certain decisions.’

Stephen Kennedy-Good, head of business law at Norton Rose Fulbright, says: ‘There is a significant drive to push back, and fight, corruption. South Africa has sophisticated legislation, including the Prevention and Combating of Corrupt Activities Act, which is a world-class, sophisticated piece of legislation that addresses corruption.’

Legislation against white-collar crime includes the Companies Act, the Financial Intelligence Centre Act (known as FICA), the Prevention of Organised Crime Act, and the Protected Disclosures Act.

Other sub-Saharan African nations have their own anti-corruption laws in place, in addition to the criminal code – although most still need to close the gap between legislation and effective enforcement. Botswana’s Corruption and Economic Crime Act criminalises active and passive bribery, according to the Business Anti-Corruption Portal (BACP), which says: ‘The maximum penalties include imprisonment for up to 10 years, or/and a fine of BWP500 000, and corporations as well as individuals can be held liable.’

Kenya has similar legislation (Anti-Corruption and Economic Crimes Act; Bribery Act), but, according to the portal, ‘adequate enforcement of Kenya’s anti-corruption framework is an issue as a result of weak and corrupt public institutions’.

In Nigeria, corruption is criminalised by the Corrupt Practices and Other Related Offences Act, but BACP warns that ‘despite a strong legal framework, enforcement of anti-corruption legislation remains weak: in practice, gifts, bribery and facilitation payments are the norm’.

Legal frameworks address economic fraudsters who make headline news and companies that cause ‘wide-ranging and cumulatively substantial “routine, everyday harm”’, according to the Oxford Handbook of Criminology. ‘In addition, there is a range of “middle-class crimes” in which tax and other frauds are committed by people who regard themselves as respectable and are so regarded by others.’ The authors suggest that the definition of white-collar crime must also include ‘Mafia-type “organised crime” involvement in major bankruptcy and VAT frauds, counterfeiting, alcohol and tobacco tax evasion/smuggling, and public-corruption activities’.

To legislate against this wide range of crime, one has to understand the motivation behind it. There are, for example, ‘slippery-slope frauds’, according to the handbook, ‘in which deceptions spiralled, often in the context of trying – however absurdly and over-optimistically – to rescue an essentially insolvent business or set of businesses, escalating losses to creditors’. At the other end of the spectrum are ‘pre-planned frauds, in which the business scheme is set up from the start as a way of defrauding victims (businesses, public sector and/or individuals)’.

Groenewald warns that legislation and regulations are not foolproof and their effectiveness is directly linked to proper oversight of their implementation. ‘That being said, it’s important to note that rules and regulations cannot cover all possible scenarios and decisions financial actors may face,’ she says.

Stricter laws don’t necessarily prevent corporate crimes, because people with the intention to do something wrong will still go ahead, says Parmi Natesan, CEO of the Institute of Directors in Southern Africa.

‘What we rather need is a culture of “doing the right thing” that is inbred into society, with zero tolerance, and real consequences, for failure to do so. Lack of consequences is a very real concern,’ she says. ‘In South Africa, elements of good corporate governance have already been incorporated in certain legislation like the Companies Act and other pieces of legislation. We call this a hybrid system between hard law – legislation – and soft law – voluntary codes.’

Kennedy-Good explains that the Companies Act sets out the legal framework for corporate South Africa, while ‘softer’ guidelines, such as King IV, set out corporate governance rules. ‘Those rules are, however, becoming more and more important, and they give additional content to the framework set out by our laws. For companies listed on the Johannesburg Stock Exchange, the listings requirements provide that certain provisions of King IV must be complied with. In that way, public companies are compelled to comply with those provisions of King IV.’

As the provisions of the voluntary King IV code of governance find their way into jurisprudence, they are becoming part of South Africa’s common law, according to Natesan. ‘Consequently, failure to meet an established corporate governance practice, albeit not legislated, may invoke liability,’ she says.

To further discourage corporate failures, the Prevention of Corrupt Activities Act makes it obligatory for any individual to report financial misconduct above the amount of ZAR100 000. Companies in the private and public sector are legally obliged to establish mechanisms for safe reporting (whistle-blowing) that allow employees to report any observed wrongdoing to HR, internal audit, the ethics officer or direct line-management.

Another piece of legislation, the Auditing Profession Act, contributes to keeping corporates on the straight and narrow. It provides for the establishment of the Independent Regulatory Board for Auditors (IRBA) and requires registered auditors to report ‘reportable irregularities’ to this board, according to Thandokuhle Myoli, project director of assurance at the South African Institute of Chartered Accountants (SAICA), which has 45 800 members.

The act also intends to ensure that auditors remain ethical and independent – a vital point at a time when the profession is recovering from the reputational damage caused by rogue auditing firms in South Africa.

To further improve audit quality, Mandatory Audit Firm Rotation (MAFR) will become effective on 1 April 2023. Myoli explains that the IRBA has identified long auditor tenure, and close relationships between the auditor and a company’s chief financial officers and audit committees as impediments to auditor independence. The IRBA has published the names of JSE-listed companies that employed the same audit firm for more than 50 years, some even for 100 years. ‘This could lead to complacency, unconscious bias or a familiarity threat that has the potential to create situations where independence is at the least perceived to be impeded and at worst can lead to an inappropriate audit opinion,’ says Myoli.

He adds that ’at this point in time, MAFR is a relatively new concept and SAICA does not have enough information to comment on its effectiveness’.

While it’s important to improve legislative and regulatory frameworks, sub-Saharan African nations still need to find the optimal balance between the promotion of business and foreign investment and the restriction of fraudulent activities, as too many laws can stifle an economy. South Africa already has world-class laws, so now is the time to enforce them. It’s up to government, corporates and society to instil an ethical culture and show zero tolerance for any criminal activity – paying special attention to white-collar crime that is often silent and routine, and able to cause great harm without any blood stains or other visible damage.