With the upswing in awareness about how our actions and buying power impact the planet, conscientious travellers are finding the promise of ecotourism more and more attractive – that promise being a reduced carbon footprint, conservation of natural habitats and endangered species, and empowering local communities.

The UN has proclaimed 2017 the International Year of Sustainable Tourism for Development. Technically, there is a subtle distinction between ecotourism and sustainable tourism – one focuses more on ecology; the other, communities – but it’s arguable that these are no longer separate issues, since humanity’s survival in the long term depends largely on our ability to protect the natural world from further damage.

It’s safe to say that as a result, ecotourism has become much more mainstream within the broader global tourism industry, and Africa – which has captured the imagination of visitors for over a hundred years with its dramatic landscapes and diverse wildlife – is no exception.

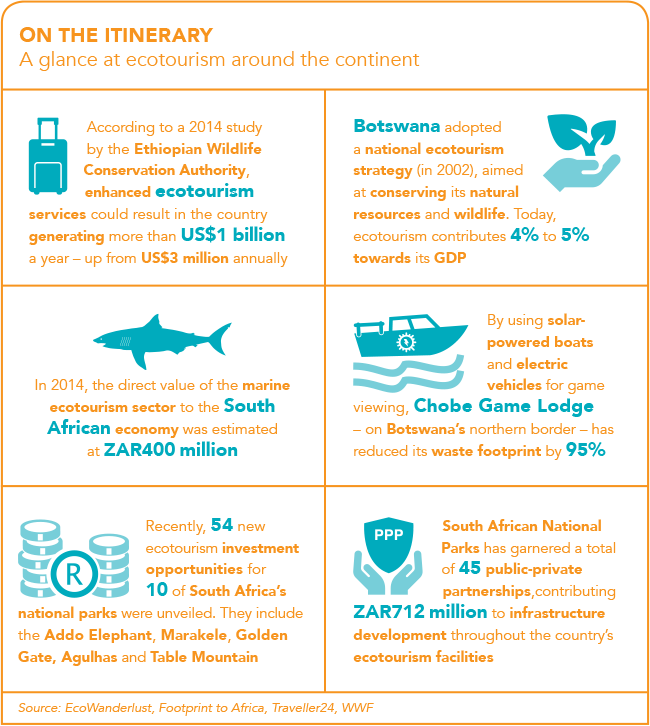

Tourism is a huge growth industry for Africa, ecotourism no less so within that. Botswana, Madagascar, Namibia, South Africa, Tunisia, Zambia and Zimbabwe were some of the first countries to fly the ecotourism flag and they now have well-established ecotourism sectors. South Africa is considered the leader of ecotourism in Africa, thanks to its popularity with travellers and solid infrastructure, and Namibia was one of the original proponents of ecotourism, with operators such as Wilderness Safaris setting up eco-lodges with the promise of handing them over to locals within 20 years.

Countries that have developing, up-and-coming tourism industries are also embracing ecotourism with more determination than their established counterparts in order to remain competitive. In recent years, Ghana has come to be considered somewhat of a pioneer in ecotourism on the continent, thanks to its community-based ecotourism, ‘which aims to create a mutually beneficial three-way relationship between conservationists, tourists and local communities’, according to the Ghana Tourism Authority. It counts hippo and wetland sanctuaries as well as many national parks among its ecotourism offerings.

In Benin, organisations such as EcoBenin have helped offset carbon emissions and improve opportunities for local employment. Visitors to Ethiopia have been rising steadily, and the ecotourism market is estimated to be worth a potential ETB20 billion.

So which countries are the most progressive in terms of their ecotourism offering?

‘Botswana’s far-sighted ecotourism model has influenced the way we operate all of our camps,’ says Keith Vincent, CEO of Wilderness Safaris, one of the continent’s leading ecotourism operators. ‘Botswana’s “low volume, low impact, high value” tourism policy has prospered and secured the conservation of land and wildlife, as well as ensured that the benefits accrued from ecotourism are also realised by the local communities.’

Namibia also has one of the most open-minded approaches to ecotourism, says Bruce See, director of Eco-tourism Africa, an initiative working in conjunction with Ecotourism Australia to bring eco-certification to SADC countries in Africa under the criteria laid down by the Global Sustainable Tourism Council, a UN initiative. ‘Their tourism board is very active and progressive, and they seem to be keeping well up-to-date and ahead of developments. The reason for this is probably that, to remain competitive with South Africa, Botswana and Zimbabwe in terms of what they can offer, they need to go to extra lengths.’

Wilderness Safaris, which operates mainly in Namibia, Botswana, South Africa, Zimbabwe, Zambia and recently Rwanda, among others, is considered one of the most successful and ethical tour operators on the continent. Established in 1983, the organisation protects more than 2.5 million ha of prime African wilderness across eight biomes harbouring 33 International Union for Conservation of Nature red-list species, all of which are increasing in those areas. It operates more than 25 camps in Botswana, providing jobs and income for 1 200 Batswana and is involved in a large number of conservation and community projects in conjunction with government partners and NGOs, such as the Wilderness Wildlife Trust and Children in the Wilderness.

‘Our greatest contribution is to have built a highly successful and sustainable ecotourism business that supports itself, does not rely on external funding, and makes an enormous positive contribution to conserving and restoring Africa’s wilderness and wildlife while empowering local people and communities at the same time,’ says Vincent.

AndBeyond, a leading luxury safari company with camps in Botswana, Kenya, Namibia, Rwanda, South Africa, Tanzania, Uganda and many other African countries, also places care of the land and its people at the heart of its business. It conducts conservation research and has reversed local extinctions at a number of its sites. In partnership with the Africa Foundation, it has handed numerous healthcare and education initiatives over to local communities, which are then responsible for their sustainability. ‘We recognise that if we are not able to get meaningful benefits to the local communities living around our wildlife areas, these areas would not sustain,’ CEO Joss Kent told the Peak magazine. ‘It is vital for the communities surrounding wildlife areas to feel the benefits flowing out of conservation, in order to support these reserves.’

This is on the positive end of the scale, where tour operators are genuinely passionate about conservation and empowerment. In many instances, however, there appears to be a wide schism between the ethos of ecotourism and the practice.

The ‘eco’ badge is a shiny, desirable drawcard for tourists. However, when management discovers the extent of the requirements, enthusiasm often wanes, says See. ‘When they understand the effort that is required, they either delegate it to someone not really competent and/or motivated to do it properly, with the result that it drags on until eventually it peters out altogether, or ends up costing more than it should to get it processed properly.’

Certification by official organisations such as Eco-tourism Africa has been undermined by a deluge of social media and travel websites claiming vague authority in this arena. ‘We are being overrun by everyone climbing on the bandwagon,’ says See. ’Booking and hospitality companies are reaching further and further into the markets and expanding their labelling based on experiences and feedback alone, companies end up with dozens of “awards” labels and other merit badges that imply compliance to good ecotourism practice, but are rarely justified.’

Unfortunately, legislation is unlikely to make up for a lack of ethical motivation unless adequately enforced, which is seldom the case. In fact, in South Africa, arguably a global leader in ecotourism, there is surprisingly no official regulation of ecotourism yet. ‘It is not the legislation that is the main problem in Africa, it is the implementation and compliance that is key to success,’ says See. He adds that South African legislation is not very strong in that it is not enforced and the incentives for compliance are unattractive given the effort required to maintain compliance. The costs of claiming and processing applications for incentives are also unwieldy and costly.

He cites the Sector Training and Education Authority (SETA) system, which makes it extremely difficult to train people, and the costs involved in training (and the cost of recovering that cost) is often more than it is worth. One of the components of good ecotourism is the inclusion of local communities and their upliftment through training and development, supply chains and so on, but because of the cost and complication of the procedures involved, many organisations do minimal training. ’Accredited’ training often is poor and below standard, but very little quality enforcement is carried out at the South African Qualifications Authority and SETA levels. These problems are echoed through other aspects of the ecotourism requirements for sustainable development.’

What’s interesting is that ecotourism, if properly implemented, should result in lower prices for consumers and greater profit for service providers – but in many instances the opposite has occurred. Rather, eco-conscious tourism is becoming increasingly privileged, with game lodges and operators charging more, not less for the peace of mind afforded by this form of tourism. ‘By looking at more efficient utilisation of resources, there are many cost savings that companies can enjoy if they implement these changes,’ says See. Once these have been adopted and embraced by the organisation, ecotourism certification also becomes cheaper as there are fewer changes to be enforced, the process is more seamless and the culture of the organisation is already primed and familiar with the concepts.

Despite the challenges, ecotourism remains a hope-filled endeavour in Africa, and is rich with opportunities for growth. According to the Africa Tourism Monitor 2016, a report published by the African Development Bank, the tourism sector in Africa is robust despite a 3.5% drop in international arrivals in 2015 from 2014. In 2015, Africa’s tourist arrivals decreased to 62.5 million, down from 64.8 million in 2014, but that’s still impressive compared to a mere 17.4 million visitors in 1990. Nevertheless, in 2015, direct travel and tourism employment in Africa as a whole totalled 9.5 million – an increase of 400 000 jobs since 2014. According to the UK’s World Travel and Tourism Council, the international tourism sector now accounts for 8.1% of Africa’s total GDP.

‘There are many new opportunities becoming available, especially due to the growth of tourism arrivals into Africa and improved access, as well as the subsequent reduced cost of access,’ says Vincent. ‘This will allow for previously ignored areas throughout Africa to either launch ecotourism ventures or develop new products and experiences. This is very encouraging for the industry, as well as for the future protection of many remote areas, not only providing opportunities for wildlife conservation and biodiversity protection, but also for the empowerment of local communities through wealth creation, such as employment,’ he says.

‘Obviously the ideal goal is to then expand these areas under the influence of wildlife and ecotourism even further, and to build many more sustainable conservation economies on the continent.’