In a welcome role reversal, an African tech start-up has been invited to solve first-world ‘smart city’ challenges in the US. As most tech innovation is brought to Africa from the US, Europe and Asia, it’s all the more exciting when home-grown companies contribute to developing global solutions.

Founded in July 2018, the local start-up currently in the headlines is Kriterion, based in Midrand, South Africa. Its goal is to create the new standard in AI driven asset performance management – a big ambition that would advance smart cities, not only in the US but also at home in Africa and elsewhere in the world.

Kriterion is partaking in a 10-month accelerator programme, sponsored by Microsoft and Intel, in Houston, Texas. ‘It’s a privilege to have been selected as the only non-US member of the first cohort to participate in the Ion Smart City Accelerator,’ says Wim Booyse, who is the MD and one of five founders of Kriterion. He explains the South African start-up’s smart city solution for Houston, where 23% of potable water is lost during the distribution process, from chlorination and filtration plants to the customers’ tap.

‘Our predictive maintenance solution will contribute towards and create a more effective water distribution and transportation network with fewer failures, and improved asset performance,’ he says. ‘The actionable intelligence provided through our platform will empower proactive decision-making and resource allocation to drive water conservation efforts and financial outcomes.’

Booyse underlines that AI tech innovation, coupled with internet of things (IoT) connectivity, is not only useful in the Houston scenario but also for addressing deep-rooted challenges facing all cities across Africa. ‘Empowering cities in Africa to serve its people and its citizens in a manner where a new “normal way of life” is established and the effective management and delivery of scarce resources such as water and electricity, becomes a new benchmark, is at the core of our AI technology,’ he says.

The Ion Smart City Accelerator startups work together with municipal decision-makers, experts and community members to understand Houston’s specific needs and then develop and refine their tech solutions accordingly. The City of Cape Town (CoCT) probably had this type of collaboration in mind when it issued its request for information in 2018, asking the public for ideas on any products or technologies to advance its Digital City services.

‘In comparing the responses received to that of the City of Cape Town’s drafted digital strategy, it was concluded that there is a definite alignment between the city’s digital roadmap and that of what the private sector was proposing,’ said Sharon Cottle, mayoral committee member for corporate services. ‘After considering the submissions the city found that there weren’t any concepts that stood out as an initiative that could fast track [our digital] journey. However, the exercise highlighted the areas which need to be prioritised, ie analytics, smart metering, mobile applications and open data/data management.’

Smart city solutions – in which services are connected, automated and easily accessible – depend on the unique context and the tech maturity of a particular city. Bustling African cities with large informal settlements and trading have very different priorities from, for example, Singapore, which is the world’s largest investor in smart city technology. The highly regulated city-state is pioneering ‘Virtual Singapore’ – a dynamic 3D model of the Asian metropolis that can be used, among other things, to simulate emergency response or predict cellular network dark spots.

In contrast, smart city efforts in Africa are often hampered by inefficiencies at national level. Such fundamentals need to be sorted out in order for e-government and smart municipal services to function. ‘The application of a smart city is much broader than technology; we are also looking at how we can deliver government services smarter by improving business processes,’ says Lawrence Boya, director of the City of Johannesburg’s smart city programme. ‘It is part of changing from the old ways of doing things which may be unsustainable and harmful to the environment, to making a meaningful contribution in building a better, sustainable city.’

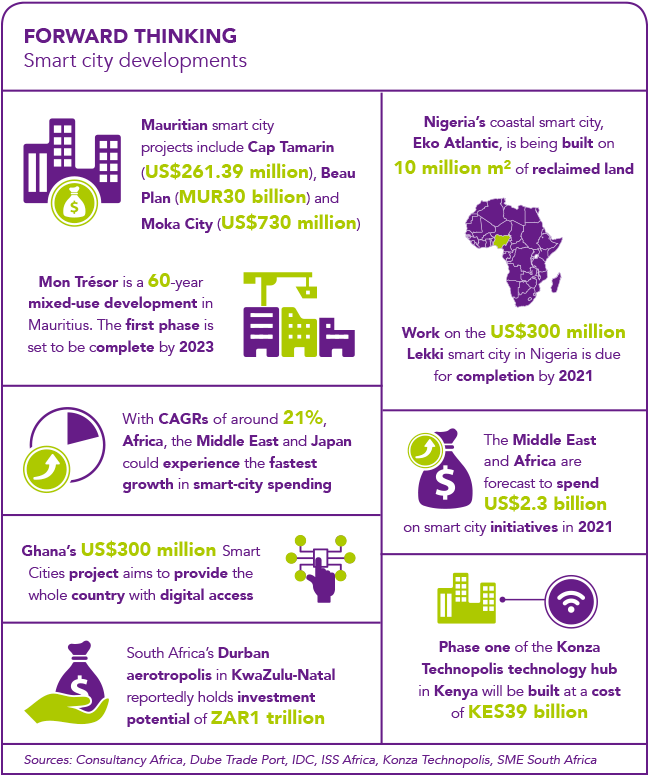

Sometimes it’s easier to build a new city than improve and retrofit existing ones. This is happening in Lagos, where a privately funded, high-end smart city is taking shape on land reclaimed from the ocean. Eko Atlantic City is set to become Nigeria’s new financial hub, a prime business and residential location with the highest standard of living. The new city will be fully connected by fibre-optic telecoms and self-sufficient in terms of power.

Other greenfield projects include Konza Technological City near Nairobi and Mon Trésor, Mauritius. In South Africa, plans are under way to create a smart ‘21st-century city’ around King Shaka International Airport near Durban, in the KwaZulu-Natal province. In August, Nomusa Dube-Ncube, the provincial minister for economic development, told the media that the ‘Durban Aerotropolis is envisaged to be a catalyst for rapid urbanisation, employment creation and to spur economic growth in the province. We are clear and resolute in the creation of an airport “smart” city’.

However, critics say that some of Africa’s smart city developments are elitist real-estate projects that – rather than solving urban challenges – serve to deepen the divide between wealthy and poor, formal and informal. It’s the role of African governments to ensure that smart city projects are integrated into the existing urban landscape and national strategic plans. This happened recently in South Africa when the Modderfontein New City project was halted. A Chinese developer bought the 1 600 ha site near Johannesburg in 2014 and wanted to invest ZAR84 billion in building a new smart urban district.

‘The aspirations to produce a high-end, mixed-used development did not fit with the City of Johannesburg’s approach. Rather than a luxurious global hub, the city wanted a more inclusive development – one that reflected the principles outlined in its Spatial Development Framework,’ write academics Ricardo Reboredo (from Trinity College Dublin) and Frances Brill (from University College London) in the Conversation. Modderfontein would have strengthened Asian corporate interests but, say Reboredo and Brill, ‘the project’s trajectory shows how African “edge-city” developments, which are generally elite-driven and marketed as “eco-friendly” or “smart”, can be influenced by a strong local government with the means and willingness to shape development’.

While there is no ultimate definition of ‘smart city’, it’s about the collaboration between the public and private sector to solve urban problems, using data analytics and technology as enablers. In short, the focus is on practical issues that improve daily life in the city rather than futuristic scenarios. Think free broadband, efficient basic services and improved communication via digital platforms, rather than driverless cars, humanoid robots and holographic billboards.

‘The city has already laid out hundreds of kilometres of broadband; it’s now time to leverage on that network in our bid to grow into a fully-fledged smart city,’ says Johannesburg’s Boya. Residents will benefit from e-learning opportunities, smart-tech enabled transport and smart policing through CCTV cameras. He notes that the municipality ‘is currently implementing various projects across departments. These are isolated, hence we are not seeing much impact at this stage. We need better co-ordination to have greater impact and to scale up the implementation’.

Vijay Narayanan, visionary innovation senior research analyst at Frost & Sullivan, agrees. ‘Currently most smart city models provide solutions in silos and are not interconnected. The future is moving toward integrated solutions that connect all verticals within a single platform. IoT is already paving the way to allow for such solutions.’

In Cape Town, there are plans to use IoT for automated meter reading and collection of sensor information in the field. Cottle adds that ‘there is a need for centralised collection and manipulation of this data for intelligent reports and dashboards. The city plans to implement an IoT proof of concept in the 2019/20 financial year’.

As Africa’s cities are progressively getting smarter, they may not be able to compete with cutting-edge Singapore. But as they improve basic services, manage traffic, security and services, everybody in the city – rich and poor – will find their daily lives running a bit more smoothly.