Anyone who has ever travelled within Africa knows that getting around many cities can be an exercise in patience thanks to hours spent sitting in gigantic traffic jams.

Ryno Verster, associate director of infrastructure and financing at KPMG, explains that many of the continent’s cities have simply not kept pace with increasing infrastructure demands because of the massive investment that such developments require. ‘You’ll reap the rewards down the line but the upfront capex required is a great stumbling block,’ he says.

The problem is that infrastructure and economic growth are closely related, as the state of a country’s public transportation system has a significant effect on its economy. ‘Often this is somewhere quite far down on the priority list,’ says Verster. But, he adds, get it right and the positive impact on GDP will be massive.

According to Richard Matchett, divisional director (transport and infrastructure) at WSP Parsons Brinckerhoff: ‘An economy is about people, quite simply put – and people are either the producers, consumers or managers of things. If your people aren’t able to engage with jobs, your economy is going to stagnate. The economy is where the money lives but it’s a chicken-and-egg scenario – with a weak economy, you can’t spend on infrastructural improvements, and without adequate infrastructure, people can’t participate in the economy.’

Founding director of the Centre for Dynamic Markets at the Gordon Institute of Business Science Lyal White agrees. ‘Infrastructure and the resultant effect on productivity eats away at around two percentage points as far as economic growth in Africa is concerned. That is quite something because Africa is growing by about 3%. It totally undermines productivity, which completely erodes the economy and economic growth.’

This is especially evident in Nairobi, Kenya, he says, which is notoriously congested. ‘It can take three hours to get across that city.’ With no obvious solution in sight for this continent-wide productivity killer, White describes the matter as ‘quite concerning’.

So how does Africa fare when it comes to public transportation infrastructure? In Kenya, the public transportation landscape has largely been dominated by the informal sector, with people getting around in matatus (minibuses). In 2012, aided by a loan from the World Bank, the Kenya National Highways Authority vowed to incorporate bus rapid transit into its transport infrastructure upgrade plans, as part of the government’s proposed mass rapid transport systems. Things did not, however, go as planned. In mid-2016, Transport Cabinet Secretary James Macharia said the KES41.3 billion project was proving difficult to implement as the existing road infrastructure lacked adequate space for bus lanes.

‘In the mass rapid transit system there are two components: the commuter rail and the bus. The bus will be very difficult [to implement] because we don’t have the lanes for the buses,’ Macharia said at the time. ‘What will come is the commuter rail, as it will use the present metre gauge rail.’

While a commuter rail project has been on the cards for several years, it is anticipated that once complete, nine transport corridors linking Nairobi estates with the city centre will be opened. According to reports, the government has entered into a public-private partnership, leaning on private investors for the US$138 million project.

Ethiopia’s capital, Addis Ababa, is home to a population of nearly 4 million. A steady influx of people has placed incredible pressure on the city’s services, particularly transportation infrastructure. Addis Ababa’s public transport system comprises the publicly-owned Anbessa city bus service, as well as the privately-owned blue-and-white minibus taxis, referred to locally as ‘blue donkeys’. The demand for public transport is high, with most buses running over capacity at peak times.

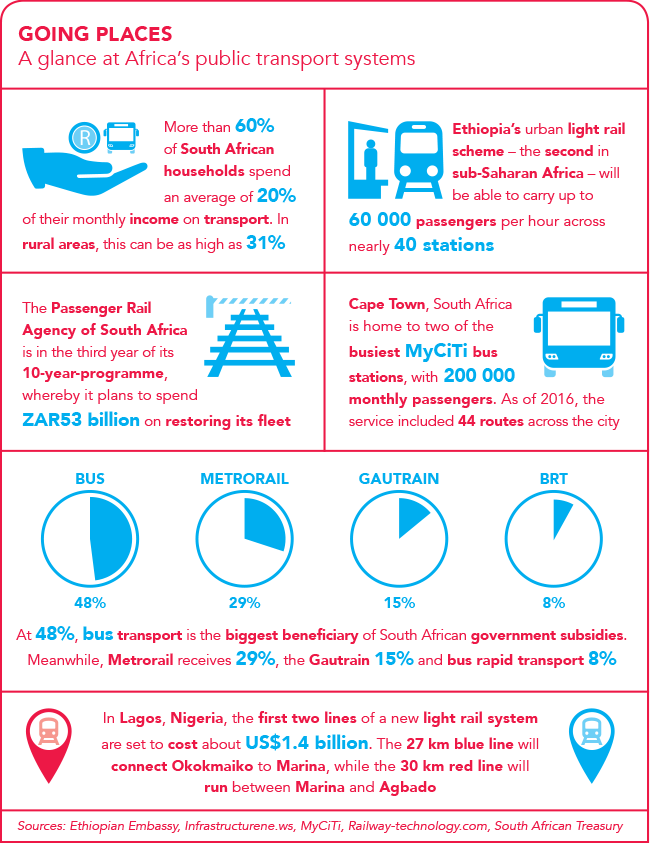

To combat congestion on the roads, the Ethiopian government commissioned a new urban metro – the second light rail system to be built in sub-Saharan Africa (South Africa’s Gautrain being the first) – the US$475 million Light Rail Project. It was primarily funded, constructed and run by Chinese institutions as a joint venture between Ethiopia and China.

The first line, which runs for 17 km from the industrial areas in the south of the capital city into the city centre, opened in 2015 and has capacity for 15 000 passengers per hour in each direction. A second east-to-west line (also 17 km long) is still under construction. The two lines will be able to carry 60 000 passengers per hour once both are fully operational, with trains running for up to 18 hours per day.

The city is also developing a bus rapid transport (BRT) network, with progress having been made on a pilot route that will be more than 10 km in length, with supporting pedestrian facilities such as walkways and crossings.

Metro projects in Africa are, otherwise, quite rare. Lagos, Nigeria’s biggest city, has had plans for a light rail transit system for some time, though construction has been continually delayed.

Other large African cities appear to be investing more in roads than in rail. Recently in Tanzania, President John Magufuli inaugurated the infrastructure and bus operations of the Dar Rapid Transit system (phase 1), which covers close to 21 km. Once all six phases have been completed, the line is expected to be 130 km long. This follows the earlier completion of a BRT system, which began operating in May 2016 with 140 buses.

South Africa has led the charge as far as public transportation networks go. It has some of the continent’s best-developed systems, which include Cape Town’s integrated rapid transit MyCiTi bus network and Gauteng’s Rea Vaya, Gautrain and A Re Yeng networks. However, the bulk of the population – 60% to 70% of the public workforce – travels on the cheapest and most widely available form of transport, namely the minibus taxi.

While there is certainly place for BRT systems and the like in public transportation infrastructure, Matchett says they require very specific circumstances. ‘Most often they work in a place where there is dense development along the corridor, and where such a corridor allows for expansion of the width of the road. But if your city isn’t structured with those types of nodal and high-density developments in place, your buses run under efficiency and your trade-off of bus lanes versus private lanes ceases to make sense. In Johannesburg, we are in this awkward position where the city needs to adapt to the transport network and, until it does, the efficiencies won’t be what we want them to be.’

Matchett cautions against a one-size-fits-all approach. ‘Just because it worked in one city, this doesn’t mean it’ll work in another. It’s difficult for transportation planners who come from a different world view to understand what they see in Africa. While they’re good at infrastructure and design, they’re not brilliant at understanding how the heart of an African city beats.’

He adds that the effectiveness of these systems – be it road or rail – is highly dependent on how the city works and has grown – and will continue to grow. As such, it’s vital to study people’s movements and patterns of behaviour, and to be sure the anticipated system will meet the transportation requirements.

‘The physical infrastructure and social behaviour infrastructure must talk to each other,’ says Matchett. ‘If people do not behave in a way that the infrastructure needs them to, you’re going to have difficulties. You must plan a system that works with the people.’

In this regard, what would help cities to develop and keep pace with their infrastructure needs is greater co-operation between different spheres of government, according to Verster. In other words, seeing retail, commercial and industrial developments as packaged together and done so in conjunction with transportation infrastructure. ‘The two are not divorced from each other,’ he says.

‘Too often, you get rampant growth of a city but the transport infrastructure lags behind. What we need is better planning of the whole city.’ This should include thinking about a multi-modal solution, says Verster, and incorporating various forms of transport into one effective system.

White agrees. ‘Light rail and BRT systems are much more than simply transport initiatives. They are economic spatial initiatives. They are about creating living and commercial areas that are a part of this development,’ he says, adding that this kind of thinking around spatial development projects is crucial for the sustainability of urban centres.