When drought gripped the tip of Africa, one of the continent’s largest fishing companies, Oceana, took matters into its own hands and invested about ZAR35 million in two desalination plants, which started operating in mid-2018. Another fishing group, Sea Harvest, also built its own desalination plant, while the Tsogo Sun hotel group and the V&A Waterfront in Cape Town announced they would do the same. They are part of a growing number of businesses and municipalities that are converting seawater into potable water as a means of risk-proofing their operations against water shortages – and in particular Cape Town’s much-publicised ‘Day Zero’, the day when the city’s supply of the precious resource was projected to run dry.

At Sea Harvest, the multibillion-rand investment into a reverse osmosis desalination plant seems to be a long-term solution. The plant in Saldanha Bay on South Africa’s rugged West Coast has been operational since March 2018. ‘The output levels have varied as we have had to fine-tune the plant to handle changing conditions throughout the first 12 months,’ says Terence Brown, operations director at Sea Harvest. ‘We are currently running at 75% capacity with full production imminent. Sea Harvest will continue to produce water well into the future as the drought is not the only pressure on the local water supply.’

According to Brown, other factors affecting the firm’s water security include unpredictable rainfall and a higher demand on the municipal water infrastructure as a result of increasing industrial development in the area. ‘The most important deliverable of the plant is 1.15 megalitres of potable water per day,’ said Brown at the launch. ‘In this way we can remain sustainable and profitable but most importantly protect jobs. Sea Harvest is the single-largest employer within the Saldanha Bay Municipality. Anything that negatively affects our ability to operate will have dire consequences on the communities in and around which we operate.’

The Oceana group also decided on desalination to maintain operations at its cannery and fishmeal-processing plants in St Helena Bay and Laaiplek on the West Coast – best known for producing more than 400 million servings of Lucky Star-branded canned pilchards annually. ‘Our desalination plants have not only secured employment for over 2 000 employees but also created approximately 40 jobs during the construction phase, as well as eight new jobs to operate and maintain the desalination equipment via a supplier maintenance and operations agreement,’ according to Imraan Soomra, Oceana group CEO.

The development of the plants and ancillary equipment has involved the expertise of desalination technology supplier ImproChem, as well as Eskom for the transformer, and several local suppliers and installers of piping, pumps and tanks. ‘Both our desalination plants have been running according to specification with no operational problems,’ says Soomra. He adds that as of the end of February 2019, both plants had jointly generated 270 million litres of water since they started operating in mid-2018. ‘The operational costs compare favourably with the municipal water rates but are offset by higher energy costs. Although many water and energy-saving initiatives seem expensive to implement in the short term, the long-term benefits for the company and the communities where we operate far outweigh these costs,’ says Soomra.

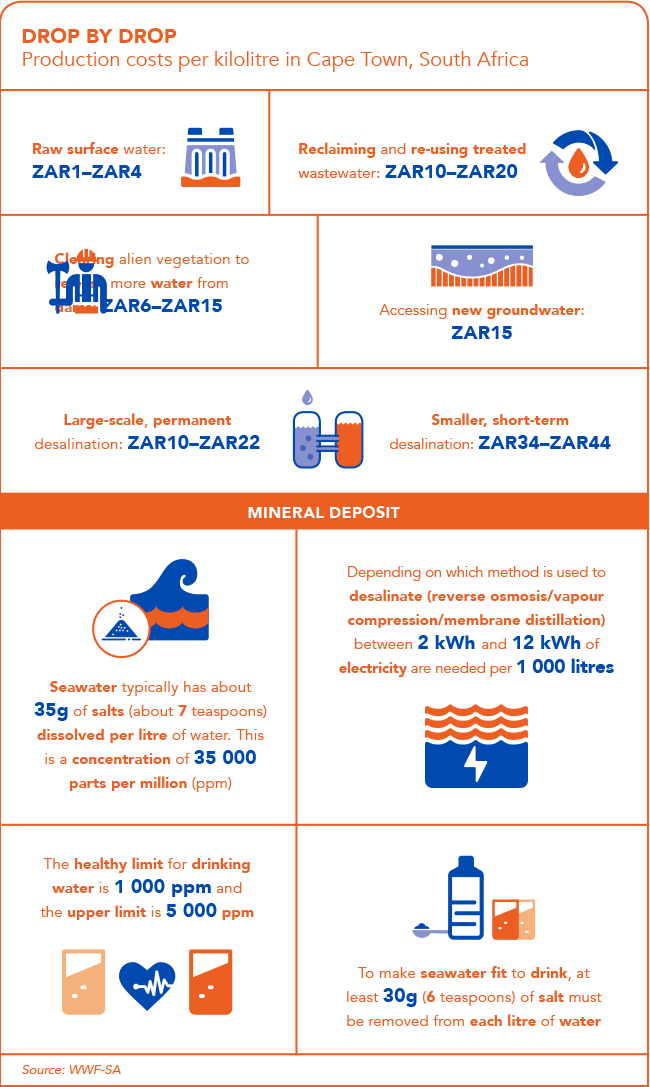

Worldwide, the cost of desalination is still two to four times as high as other sources, according to WWF-South Africa. Several factors play into this, including the capital outlay for the equipment, the cost of energy, and the labour to install and maintain the operations. As a guideline, WWF-SA says the cost for Cape Town would be between ZAR10 and ZAR22 per kilolitre for large-scale, permanent desalination, and from ZAR34 to ZAR44 for a smaller, temporary set-up. Raw surface water costs between ZAR1 and ZAR4 per kilolitre and reclaiming and re-using treated wastewater between ZAR10 and ZAR20. However, advances in technology and lower production expenses through larger-scale plants or renewable energy could make desalinated water in Africa more cost-effective.

Desalination involves removing salt and minerals from salty water, notably ocean water but also brackish water from inland sources such as rivers or boreholes. According to Veolia Water Technologies SA, the market for brackish water desalination is growing and already accounts for roughly one-quarter of all water desalination worldwide. ‘Acid mine drainage and other inland water streams with high levels of total dissolved solids can be turned into high-grade fresh water with water desalination technologies,’ Veolia states on its website. ‘By separating salts, heavy metals and other impurities from water, companies achieve numerous benefits: fresh water desalinated from brine streams can supplement existing water supplies; polluted water is reclaimed and made less environmentally hazardous; the need to transport water to water-stressed locations is reduced; and the sale of water desalination by-products, such as salt and other minerals, can create additional income and supplement the plant’s operating expenses.’

Desalination is a proven technology that has been used around the world, according to Werner van Zyl, associate professor of chemistry and a lecturer in sustainable energy and water systems at the University of KwaZulu-Natal. ‘There are a number of ways of doing this, but the only process that ticks all the boxes in terms of catering for large volumes, environmental impact and cost, is reverse osmosis,’ he writes.

Reverse osmosis essentially filters water at a molecular level, by forcing salty water through a semi-permeable membrane that separates the salt from the water. However, the resulting concentrated brine is typically pumped back into the ocean, which raises environmental concerns. According to the International Desalination Association (IDA) in January, 90% of the desalination capacity that had been contracted since 2010 employs membrane technologies, with the use of thermal technologies for large-scale projects remaining concentrated in the Middle East. There are nearly 20 000 desalination plants worldwide producing water for more than 300 million people.

The largest seawater desalination award on the IDA’s inventory list is Rosarito, Mexico (378 000 m3 per day), followed by projects in the UAE and Saudi Arabia. The association adds: ‘In sub-Saharan Africa, Kenya’s Mombasa County awarded two projects of 100 000 m3/d and 30 000 m3/d, while three smaller projects were awarded in Cape Town to help avert “Day Zero”.’

Yet the city’s three temporary desalination plants in Monwabisi, Strandfontein and at the V&A Waterfront are only an emergency solution and will be decommissioned at the end of their service agreements, around mid-2020. Xanthea Limberg, City of Cape Town mayoral committee member for water and waste, says permanent desalination offers a ‘drought-proof water source’ for the growing city. ‘As such, desalination is highly likely to form part of Cape Town’s future water mix.’

This view is echoed by Greg Matthews, environment and energy (Africa) director at engineering company WSP. ‘Desalination in the Western Cape has previously been viewed as a potential temporary measure when, in fact, it should be viewed as a long-term solution, despite its challenges,’ he says. ‘We can learn a lot of desalination lessons from the many countries worldwide that have already fully embraced desalination technologies, such as plant oversizing in Australia. ‘Storing desalinated water underground has started to be discussed by experts and should continue to be researched, as this both recharges groundwater aquifers and prevents evaporative losses.’ Six other South African municipalities are also using small-scale reverse osmosis plants to augment their bulk water supply: Mossel Bay, Knysna, Bitou, Ndlambe, Cederberg and Richard’s Bay.

The country’s first desalination plant powered entirely by renewable energy was commissioned in October 2018. The ZAR8.6 million plant in the small southern Cape town of Witsand, Hessequa Municipality, is activated by PV solar panels and shuts down and starts automatically according to the sunlight, producing a daily average of 100 kilolitres of drinking water.

French renewable water firm Mascara developed this ‘nature-inspired resilient solution’, which is distributed locally by Turnkey Water Solutions. The innovative green technology does not rely on batteries and is designed for both seawater and brackish water. Mascara has already launched its technology in other African countries: on Mauritius’ Rodrigues island and in six locations in Mozambique’s Gaza province.

It’s clear that the continent needs to manage its water resources and demand smarter solutions, and use the available freshwater more efficiently, but the discussions around desalination are becoming louder.

If the solar-powered reverse osmosis plants prove to be successful, they may be one solution to tackling the drought risk, paving the way towards a more water-resilient future.