Africa’s economic boom is driving a realignment of the ports through which the continent trades with the rest of the world. While there are impressive new greenfields developments, notably Lamu in northern Kenya, it is initiatives to deepen, enlarge and improve existing major harbours which hold the key to the continent’s future.

The contest for seaborne business in East Africa demonstrates the relationship between harbours, their efficiencies, links to the hinterland and economic growth. The port of Mombasa in Kenya announced significant improvements this year. The container terminal achieved 165 moves per hour in June, surpassing the previous record of 150. This is the latest in a series of impressive efficiency improvements at the harbour since the May 2017 opening of the 470 km, US$3.2 billion standard-gauge railway (SGR) linking the harbour to the Nairobi dry port.

According to Hellenic Shipping News, Mombasa is now moving 10 times the number of containers it had cleared previously. In January 2018 it was shifting only 108 TEUs (the standard terminology for a 20-foot equivalent unit container) per day. By September, the figure had climbed to 905 TEUs per day. With dredging since 2012, the port of Mombasa is the deepest in East Africa and can handle post-Panamax vessels of more than 100 000 tons.

The SGR has been accompanied by a three-phase expansion programme at the harbour. This includes a second container terminal, currently under construction, an additional 900m of quay length and administrative improvements to reduce cargo clearance times. Mombasa is important because it is East Africa’s best bet for a genuine world-class hub container port. According to Francois Botes, transport and logistics expert at PwC South Africa, ‘the global trend in recent decades has seen the emergence of hub ports that facilitate dominant volumes of global trade in and out of a region’. For example, he points out, the rise of Rotterdam and Antwerp as hub ports in Europe has reduced many long-established harbours to ‘feeder ports’.

Mombasa will be complemented by a new port currently being built at Lamu. The first of Lamu’s three berths is expected to be ready this year. The planning of the project paid attention especially to logistical links to Ethiopia and South Sudan. However, concerns have been expressed about the port’s location, close to the Somali border. The threat of terrorism and a maritime border dispute between Kenya and Somalia may discourage shipping companies. These threats are probably the reason why Uganda chose to route its oil pipeline through Tanzania rather than Lamu, as originally envisaged.

The prospects for any port are closely tied to what is happening inland. ‘The key determinants are shipping line connectivity, the amount of trade passing through a port and the size of the hinterland,’ says Botes. ‘Hub ports are large regional container or break-bulk ports with high volumes – over 2 million TEUs per year – and direct shipments carried by very large vessels.’ Although Durban in South Africa is the only port in sub-Saharan Africa that qualifies in terms of this definition, Botes believes at least one hub port is in the process of emerging in both East and West Africa.

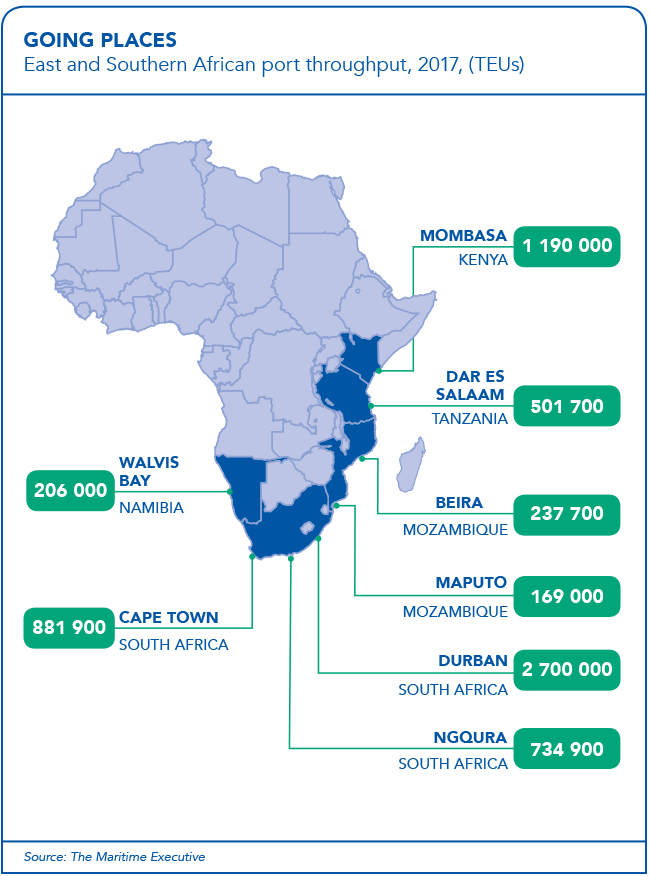

In East Africa, Botes considers the leading hub port contender to be Mombasa, on account of its larger hinterland and operational efficiencies. In West Africa the leader is Abidjan in Côte d’Ivoire, although it faces competition from Tema in Ghana and Apapa in Nigeria. Hub ports are critical to the opening and development of their hinterlands. ‘This is not to say that hub ports should always be prioritised. Rather, investment should focus on a port’s inherent function,’ says Botes. Mombasa handled 1.19 million TEUs in 2017, more than twice the volume that passed through Dar es Salaam (501 700 TEUs). Although the Tanzanian port considers itself a competitor for hub port status, Dar es Salaam is incredibly congested. Volumes exceeded actual throughput capacity by a factor of two. ‘Given the infrastructure constraints, the staff at Dar es Salaam have actually done an incredible job,’ says Botes.

There is much trade in East Africa for ports to compete over. According to the AfDB, economic growth in East Africa is expected to continue growing at close to 7% in 2019, led by Ethiopia at 8.2% and Rwanda at 7.8%. By contrast the best regional growth outlook in the rest of the continent is West Africa at 3.3%. Darron Wadey of maritime industry analysts Dynamar says ‘East Africa is growing and expanding its influence. [In the period] from 2013 to 2017, GDP rose by 25% at the expense of Southern Africa. It is the landlocked countries pushing GDP growth and not so much their coastal neighbours’. But this process, he argues, is driving the need for greater port efficiencies.

Namibia’s Walvis Bay illustrates the point about the importance of the hinterland and an appropriate definition of a particular harbour’s role. It has deliberately set out to become a logistics hub for SADC by 2025. Driven by a public-private partnership, the Walvis Bay Corridor Group, it has focused on the development of trade with neighbouring countries, especially Botswana, Zambia and the DRC. Just 20% of Walvis Bay’s throughput is Namibian in origin. The harbour’s biggest single customer is the Zambian mining industry. According to the 2018 Namibia State of Logistics report, Zambia accounted for almost 60% of total volume between June 2017 and March 2018. That the Zambian mining industry should choose Walvis Bay ahead of similarly distant ports in Angola, Mozambique and Tanzania is testament to the Namibian harbour’s efficiency and inland logistical links.

The WEF’s latest Global Competitiveness Report rates Walvis Bay first in SADC in terms of port efficiency. The Namibian port ranks 41st out of 141 countries, followed, in SADC, by South Africa (51st) and Tanzania (79th). Walvis Bay is expecting to commission a new US$300 million container terminal later this year, increasing the harbour’s capacity from 350 000 TEUs per year to more than 750 TEUs per year. The new facility is built on 40 ha of reclaimed land within the existing port area. The harbour includes dry ports serving Zambia and Zimbabwe, as well as ship and oil rig repair facilities.

Emerging ports in East Africa include Berbera in Somaliland, Bosaso in the quasi-republic of Puntland (previously part of Somalia) and Assab and Massawa in Eritrea. Most (95%) of Ethiopia’s burgeoning trade currently goes via the small enclave of Djibouti, but this may be in the process of shifting.

Djibouti boomed when Ethiopia cut links with neighbouring Eritrea, the site of its ‘natural’ link with the rest of the world, the port of Massawa, after a war that saw Eritrea gain its independence in 1991. The Eritrean ports went into hibernation while Djibouti forged ahead. In 2006, it brought in one of the world’s major port operators, DP World of Dubai, to run the container terminal on a 50-year lease. The port was linked to Ethiopia’s capital, Addis Ababa, by an electrified rail link built with Chinese capital. However, in July 2018 Ethiopia and Eritrea finally signed a peace deal and reopened their border, igniting the prospect of re-engaging with the Eritrean Red Sea ports again.

In the meantime, Djibouti has fallen out with DP World and nationalised the container terminal in September last year. The result, says Wadey, is that both DP World and the Ethiopian government are in the process of developing alternatives. DP World is currently part of a joint venture that includes the Ethiopian government and is involved in developing Berbera in Somaliland. The first phase involves a 400m quay, three new mobile harbour cranes and the development of a free zone to create a new regional trading hub. Together, these will ‘enable more ships to be served at and ultimately increase the flow of trade to both the country and the region’, says DP World CEO (Middle East and Africa), Suhail Al Banna. He comments that ‘we are witnessing a transformation in the capacity of this major infrastructure asset, benefiting people both here and across the Horn of Africa’.

Harbours and economic development are intimately linked and both are a part of the consolidation of statehood. The continent’s growth drives the development of ports, including the development of greater efficiencies in established harbours, and is in turn promoted by greater access to the world.