It falls from the sky. It runs through our rivers and fills our Great Lakes. And in some parts of Africa – like the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance dam – it generates the electricity that powers the continent. Yet water remains Africa’s most stressed resource.

‘While there are pockets of either reasonable rainfall or access to key water sources, the reality is most of the available water does not support the vast geography of Africa,’ according to Vinesan Govender, engineering manager at Xylem Africa. ‘Averaged out, Africa is water stressed. Water sources are few and far between and often impact more than one country. Take the Nile as an example: it supports multiple countries and can be a contention on how to manage across the various countries.’

Govender, like many people in the industry, believes that Africa needs a unified approach to water. Guillermo Gallego, key account manager for Africa at Idrica, says the COVID-19 pandemic will bring about major changes in the way water services are managed.

‘On the one hand, more attention will be paid to improving the resilience of water infrastructure, through the implementation of early-warning systems to deal with episodes caused by climate change, migratory movements and pandemics,’ he says. ‘On the other hand, it will be necessary to allocate greater financial resources to the renewal of infra- structures and the optimisation of the services provided, strengthening both the use of water resources – which are increasingly scarce – and the use of treated water for environmental and other human-related purposes.’

Gallego sees the digital transformation of the sector being enhanced through the development and adoption of new technological solutions. ‘Water management tends more and more towards specialisation and modernisation as the best way to adapt to an increasingly uncertain future,’ he says, adding that ‘we must be more united and show more solidarity in order to face a new, yet unknown, paradigm’.

Xylem and Idrica are among a handful of companies that are leading the digitalisation of water management across Africa. Inzalo Utility Systems is another. Using Sigfox’s internet of things (IoT) technology, Inzalo Utility Systems recently introduced the AquaFlow system, which is designed to detect leaks, manage payments, control water flow and transmit data across all types of environments. ‘It’s a truly smart water-management device that combines the basics of prepaid water metering with flow-limitation controls and water-loss prevention tools,’ according to Inzalo Utility Systems CEO Sbonelo Mazibuko. ‘The AquaFlow, one of our next generation of advanced metering infrastructure solutions, can transmit data wirelessly to municipalities or water-service provider databases and receive commands remotely.’

The AquaFlow retrieves accurate meter readings, transmits meter usage, and can be configured to operate within specific para- meters and used as part of a prepaid token system to ensure users pay for the water they use. ‘By using Sigfox to communicate data and information to the municipalities or water service providers, the AquaFlow is leapfrog- ging existing infrastructure and connectivity limitations. It also keeps the costs down, as Sigfox is inexpensive and has low power demands,’ adds Phathizwe Malinga, MD of Sigfox partner SqwidNet. ‘The network is a reliable solution that plays a big role in driving IoT adoption both locally and abroad. This is not only relevant in terms of improved water management, but also in terms of any IoT solutions that can help people and companies bypass the limitations of infrastructure and geography.’

AquaFlow is one smart metering solution. Xylem’s Sensus is another. Whichever system is implemented, Govender argues that ‘the need for adopting smart water metering is an absolute’.

Smart metering tends to be based on a centralised system, where flows are monitored by a utility or a command centre. But that approach has its limitations, especially on the continent.

‘We have pockets of urbanisation that are driving the growth of Africa, but [the continent] still has a lot of rural communities,’ says Govender. ‘Therefore, the approach to smart water meters needs to address both dynamics. One needs to adopt “district metered area” [DMA], which is a decentralised approach. As urbanisation and infrastructure links these rural communities, these DMAs are also linked, building the centralised network.’

Malinga sees it in much the same way. ‘Finding the right solution requires collaboration and partnerships,’ he says, using South Africa as a model for the rest of the region. ‘It needs the innovative thinking of the South African entrepreneur and the use of technology that can handle the complex South African environments. This is a country that demands solutions that can cope with rural areas, limited infrastructure, poor connectivity and harsh climatic conditions. You have to build them in South Africa, for South Africa.’

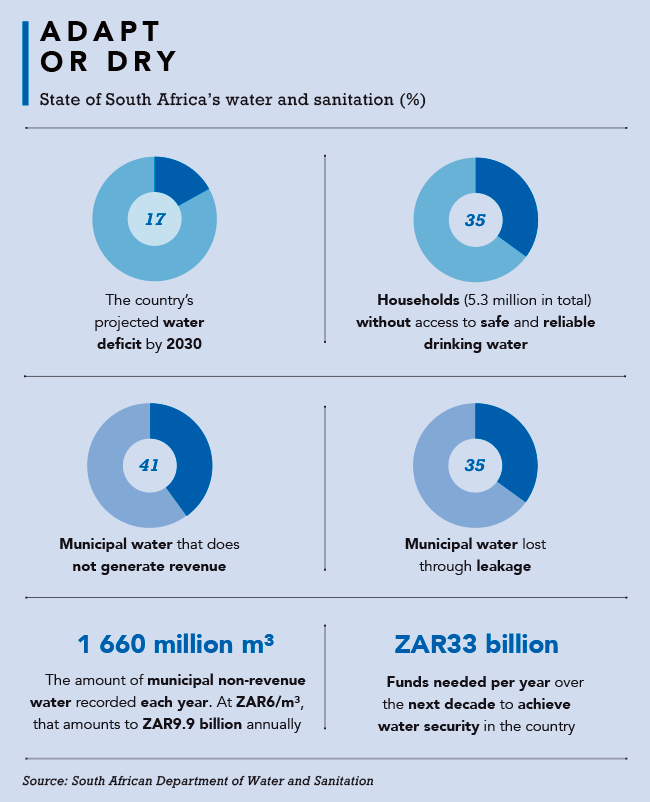

Malinga warns that the country’s – and, by extension, the continent’s – social and economic development is being held back by water shortages and lack of access to quality water. ‘On top of this, our inability to collect all the due revenues for the water supplied cripples our municipalities’ ability to provide other basic services as well,’ he says.

‘We need to find ways of managing the water resources we have more effectively, and overcoming the challenges of limited infrastructure and investment. This will have the knock-on effect of protecting this precious resource from misuse and ensuring that there is improved water security for the future.’

For Govender, the problem goes far deeper than just making sure that people pay their water bills. ‘Without metering, communities just use water with no consideration,’ he says. ‘However, with these metering solutions, it raises the awareness and culture of responsible water usage. Smart water, therefore, is not only about billing, but also creating awareness, managing non-revenue water and changing behaviours.’

Africa, like the rest of the world, has a culture problem when it comes to water. Many water users see it as being a utility, like electricity, which is infinitely producible and renewable. That single-use approach will be our collective undoing, warns Govender.

‘Open a tap and water runs out. Flick a switch and we have electricity. So we easily equate these utilities,’ he says. ‘The reality, however, is that water is essential for basic survival while electricity, gas and so on, aren’t necessarily [so].

‘Further to that, all water is just not the same. Achieving potable water quality is very different to achieving quality in other utilities. The product of electricity can be obtained from other sources, but you can’t live without water. This makes these utilities incomparable.’

Water is also limited as a resource, adds Govender. ‘You cannot generate new water or find an alternative to water. We have to really take good care of our water, or our mere existence is at risk. With these dynamics, it is critical to have a water life-cycle management strategy, as “holes” in the system can lead to losses and contamination of water. Ensuring that water is taken, used and returned responsibly will allow for more sustainable use of water and an overall better quality of water.’

Smart metering has emerged as a viable solution to this problem, promising significantly reduced waste, and far better levels of water quality. There are, of course, limits. ‘In urban Africa, smart water can be integrated into smart-city design,’ says Govender.

‘But smart metering has to be one part of managing the water across the cycle – in other words, consumption and reuse of water. In rural Africa, meanwhile, water use is for subsistence and agriculture. Managing water in this context is more about awareness and culture of responsible water usage.’

Yet, as Idrica’s Gallego underlines, ‘technological solutions related to the management of the entire water cycle are positioning them- selves as a strategic asset. They guarantee the continuity of technical, commercial and financial operations of drinking water and basic-sanitation service providers, thanks to a continuous and integrated flow of data’.

As potable water becomes scarcer – and more of a cross-border political issue – that’s a compelling argument in favour of smart water management, which starts and ends with smart metering.