In April 2019, a ZAR400 million agroprocessing facility for Woolworths was officially launched in the OR Tambo International Airport special economic zone (SEZ) in Johannesburg. The factory is expected to create 600 jobs over two years and become the country’s first five-star Green Star-rated industrial site as certified by the Green Building Council South Africa.

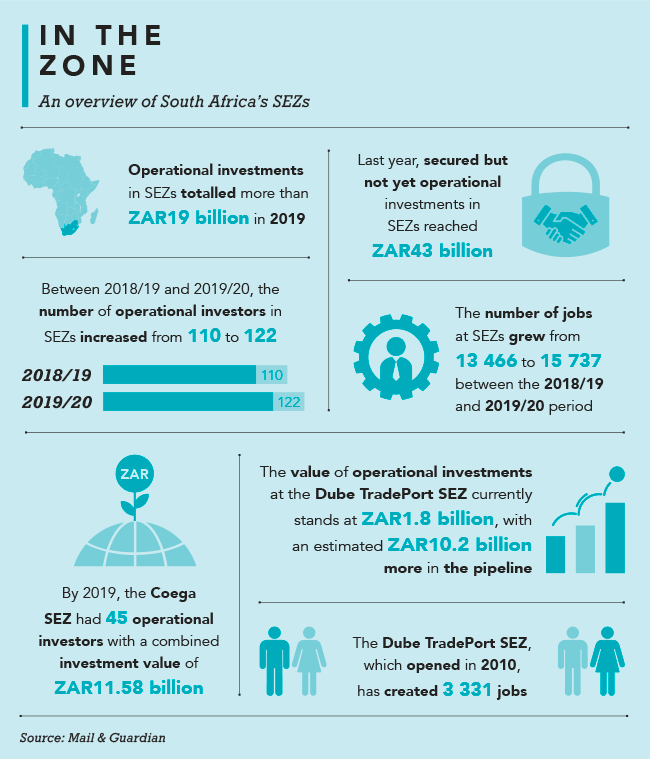

In September 2019, a Taiwanese electric solutions manufacturer announced the construction of South Africa’s first fuel-cell factory at Dube TradePort SEZ near Durban. CHEM Energy SA intends to create a new supply chain involving local labour and businesses in the production of fuel cells that support telecoms networks during electricity outages and that offer off-grid solutions.

In February 2020, Coega SEZ near Port Elizabeth reported the signing of five new lease agreements over the past year, valued at more than ZAR110 million.

‘In addition, five more investors have pledged another ZAR573 million, even though the lease agreements have not yet been signed. We hope to finalise the negotiations this year,’ says Ayanda Vilakazi, head of marketing and communications at Coega Development Corporation (CDC). ‘Currently, the total number of operational investors at Coega is 45 with a combined investment value of ZAR11.58 billion in private-sector investment and ZAR9.53 billion in FDI. In the 2018/19 FY, CDC created 15 934 jobs – 7 815 accumulative operational jobs and 8 016 construction jobs. Since its inception in 1999, the organisation has created 120 990 jobs and trained more than 100 000 people.’

CDC’s major investors include the first large-scale independent power project endorsed by South Africa’s Department of Energy, the Dedisa peaking power plant (ZAR3.5 billion); Chinese car manufacturer BAIC SA (ZAR11 billion); Chinese truck manufacturer FAW SA (ZAR600 million); and South African cement manufacturer CEMZA (ZAR600 million).

Two land-based aquaculture investments are also under way. One is a 400-ton abalone farm (with an investment value of about ZAR358 million) set to create more than 400 jobs and expected export earnings of ZAR129 million a year, says Vilakazi. The other is a ZAR400 million recirculation facility to farm barramundi (Asian sea bass) for the Saudi Arabian, Italian and Australian markets. This could generate 128 jobs with export earnings of an estimated ZAR300 million a year.

Coega is Southern Africa’s biggest SEZ regarding the number and value of investment and hailed as a best practice model for Africa. Strategically based at the deepwater port of Ngqura, it may soon also become an air-cargo hub, as media reports suggest Port Elizabeth Airport might be relocated to the SEZ.

‘The greatest attraction of SEZs for investors is their enablement in terms of infrastructure and intermodal linkages. Traditionally SEZs are built close to the coast to facilitate exports,’ says Ongama Mtimka, a lecturer and political analyst based at Nelson Mandela University (NMU) in Port Elizabeth. He explains that investors are also attracted to SEZs by their ecosystem of industry clusters and the tax and customs incentives that make it easier to conceptualise, start and get projects operational.

SEZs are ‘geographically designated areas set aside for specifically targeted economic activities, supported through special arrangements and systems that are often different from those that apply in the rest of the country’, according to the Department of Trade and Industry (dti). The focus is on accelerating growth and promoting industrial decentralisation through attracting FDI, promoting value-added exports, creating jobs, and building industrial clusters and regional economic hubs.

The government has been pushing SEZs to spread economic opportunities to rural and marginalised regions. The goal is a more inclusive economy that stretches beyond the industrial hubs of Gauteng, eThekwini-Pietermaritzburg and the Cape Peninsula (which, according to the dti, account for about 70% of the nation’s gross value add).

‘SEZs are a popular tool for governments to revitalise their economies and pilot new policy reforms, because they allow for experimentation in a focused manner in a globalised world – they enable innovation and problem-solving dynamically among the many stakeholders of business, government, society and labour at a local level for global value chains,’ says Kaashifah Beukes, CEO of Saldanha Bay industrial development zone (SBIDZ) on the West Coast, two hours by car from Cape Town.

For South Africa, she adds, SEZs ‘represent a vital opportunity for us all to effect the change we sorely need in our struggling economy and stressed societies’.

Strictly speaking, SBIDZ is a freeport and an SEZ. The government has replaced its IDZ programme with the SEZ programme and converted all IDZs into SEZs. The dti explains that the SEZ Act of 2014 is more co-ordinated and far-reaching than the IDZ programme of 2000, which was narrowly focused on seaports to attract export-oriented FDI. However, some IDZs have kept their names.

In South Africa, the incentives for operating within an SEZ include a reduced corporate tax rate of 15%, value-added tax and customs duty suspension in customs-controlled areas, building allowances, employment incentives, as well as preferential land rental and utility rates.

The growing number of SEZs in Africa will play a role in drawing investment to the continent in the coming years, according to the UN Conference on Trade and Development.

‘There are an estimated 237 SEZs in Africa, some still under construction, along with more than 200 single-enterprise zones (so-called free points),’ its 2019 World Investment report states, adding that SEZs operate in 38 of the more than 50 economies on the continent, with the highest number in Kenya (61). ‘The three largest economies of the continent – Nigeria, South Africa and Egypt – all have well-developed SEZ programmes.’

South Africa currently has 10 designated SEZs (or 11, depending on who’s counting) plus several more in the planning stages. The following five SEZs are fully operational (in chronological order of their designation): Coega (specialising in general manufacturing, agroprocessing, aquaculture, business processing services and auto); East London (general manufacturing, aquaculture, agroprocessing, auto); Richards Bay in KwaZulu-Natal (manufacturing, storage of minerals, and logistics); Dube TradePort (auto, electronics, fashion garments); and Atlantis in the Western Cape (renewable energy and green tech).

Saldanha Bay (oil and gas, marine repair, engineering and logistics) is on the verge of becoming operational. By February 2020, it had a pipeline of 60 investors and 11 signed lease agreements with an investment value of more than ZAR3 billion.

Other designated but not yet operational SEZs include the multi-site development at OR Tambo Airport (beneficiation of precious metals and minerals, and perishable food); Musina-Makhado in the Limpopo province (agroprocessing, mineral beneficiation, and petrochemicals); the multi-modal logistics hub Maluti-a-Phofung in the Free State (multi-sector); and the latest addition, Nkomazi in Mpumalanga (agroprocessing and logistics hub). The dti is also proposing additional SEZs at Bojanala in the North West, Upington in the Northern Cape, Tubatse in Limpopo and Mthatha in the Eastern Cape.

Much of the action will take place in South Africa’s Gauteng province, which Premier David Makhura plans to turn into a single, multi-tier and integrated SEZ. In line with this vision, an automotive SEZ was launched in November 2019. Tshwane Automotive SEZ is situated next to Ford’s Silverton vehicle assembly plant in Pretoria, from where it intends to expand production and the local manufacture of components. The province also has plans for a high-tech SEZ in Gauteng as well as one for platinum beneficiation in Springs, and possibly another to revitalise the Vaal Triangle area around Vereeniging.

The Tshwane Auto SEZ alone is hoped to create 6 700 local jobs, focusing on the communities of Mamelodi, Nellmapius and Eesterus. ‘The public-private partnerships are beginning to unlock the growth and job-creation potential of different regional economies or corridors,’ says the Gauteng Growth and Development Agency. ‘This is social compact in action.’

NMU’s Mtimka has researched the socio-economic impact of Coega SEZ, with similarly encouraging results. ‘We noted a rise in middle-income jobs as workers tended to be better paid in the SEZ,’ he says. ‘In another key trend, almost all the companies we interviewed in 2016 said they were going to expand within the next five years. It’s been interesting to watch that since then quite a number of investors have managed to expand in the SEZ.’

The potential to scale businesses, create employment and diversify the local economy is a huge factor in the SEZ programme. There’s also the willingness to be open to new things. At Coega, discussions involve investing in ‘weed’ – building greenhouses and processing facilities for high-value pharmaceutical cannabis. This is something that would have been illegal not long ago but now presents an innovative economic opportunity, which is exactly what SEZs are about.

By Silke Colquhoun

Images: Infrastructure Photos, Brand South Africa/Flickr