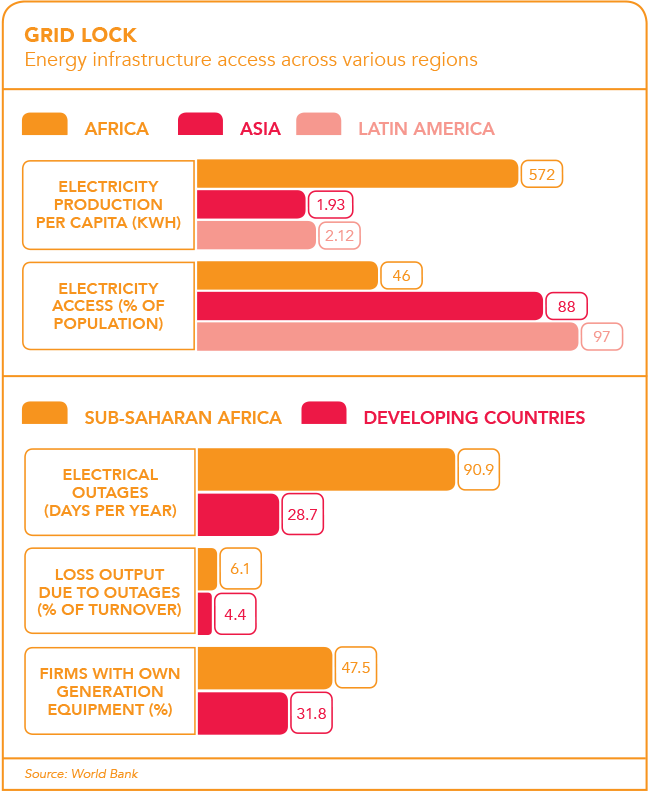

The unchallenged route ahead for African countries is infrastructure-led development. Within the paradigm, it is energy, and especially renewable generation, that currently commands centre stage. There are just reasons for this. Good and consistent returns for investment in energy will strengthen both confidence and systems with a knock-on effect in other infrastructure sectors. But while the plan is clear, the money flow contracted in 2017, necessitating a review of the hurdles to deepening the African market.

Jay Govender, director and national head of projects and infrastructure practice at law firm Cliffe Dekker Hofmeyr, says that ‘across the continent, it’s the energy space that has seen the most activity’. She argues that South Africa’s recently published Integrated Resources Plan (IRP) is enabling the country to rejoin a renewables trend that it was instrumental in establishing.

Investec’s head of power and infrastructure finance team, Andre Wepener, agrees. ‘There has been a consistent shift from traditional sources of power towards renewable sources in recent years,’ he says. He attributes this to the ‘growing recognition of the environmental benefits, as well as the reduction in cost of renewable technologies’.

The renewable energy market has a critical role to play in deepening markets for infrastructure finance in Africa more generally. Project finance is a complex and sophisticated game involving multiple players sharing varying levels of risk and commitment. Mobilising capital is only part of the issue. Risk capital will only go to jurisdictions where reliability, transparency and clear regulation are proven. Those are all areas determined by government. By global standards, Africa’s markets for infrastructure finance are mostly new and extremely vulnerable. The 2018 UNCTAD World Investment report showed FDI was down 21% in 2017 on the 2016 numbers, to US$42 billion.

Kieran Whyte, head of energy, mining and infrastructure at legal consultants Baker McKenzie, argues that ‘investment in the (renewable energy) sector had in some instances stalled due to regulatory and political uncertainty, as well as economic conditions in particular countries in Africa’. The UNCTAD figure shows that the drop in FDI in 2017 happened mostly in oil-producing countries, especially Nigeria and Angola. By contrast East Africa was down just 3%, and Morocco actually enjoyed an increase.

These numbers parallel global trends with the worldwide figure being down 23% for 2017. Interest in Africa was badly hit by the commodities slowdown after 2014. Within this pattern, however, there has been an increase in the flow of funding from China to Africa. Whyte says there is a clear shift in Chinese lending towards the power sector. ‘This is much more sophisticated outbound lending than the cliché about China investing in African minerals and rail to get commodities to China to feed manufacturing,’ he says.

While there are panicky myths about the Chinese presence in Africa, and Chinese investment has grown exponentially in the past decade, it is not the biggest foreign investor in Africa. Indeed, China’s FDI into Africa in 2016 (US$40 billion) makes it only the fourth biggest foreign investor by FDI stock after the US (US$57 billion), the UK (US$55 billion) and France (US$49 billion). In 2016, Chinese investment was only just a bit more than twice that of South Africa (US$24 billion), according to the latest UNCTAD data.

China’s entry into the market has to be seen as good for its main driver – competition. But it is far from true that Chinese money is always cheaper. The US$900 million 350 MW Cenpower project in Ghana involved a large Chinese bidder. But it could not beat the price of the package put together by a consortium of South African banks, including Rand Merchant Bank, Nedbank, Standard Bank and the Development Bank of Southern Africa (DBSA). This consortium ended up being the winning bidder for the US$650 million debt component of the project’s funding, with the DBSA committing to US$53 million of the total financing costs.

While renewable energy is just a small portion – perhaps one-tenth – of the total infrastructure market in sub-Saharan Africa, it is in this space that financing techniques and strategies are pioneered and proven. South Africa’s renewables programme has shown, for instance, that finance institutions are far more comfortable with competitive tenders or energy bid auctions – where consortia put together lowest-tariff proposals and government selects the most cost effective – rather than with renewable energy feed-in tariffs (REFiT), where the state sets a maximum tariff. The former is an invitation to the private sector to see how low their bid can come in, whereas the latter is a straitjacket that stifles innovation, to the detriment of local consumers.

Yet, while South Africa has demonstrated that competitive tenders deliver cheaper electricity to consumers than REFiT, they are no universal panacea. Govender argues that with prices of electricity coming down in every bid process, funders are becoming worried about where the lowest tariff point will be. If the price continues to come down, at some point returns will become unsustainable, she points out.

Wepener argues that ‘the greatest opportunities are in countries where there are well-structured programmes to procure power projects’. He considers South Africa’s renewables programme to be the exemplar, and comments that the lessons are starting to be applied in other African jurisdictions. ‘We are seeing similar structures in other countries, most recently in Namibia and Zambia,’ he says.

South Africa’s Renewable Energy Independent Power Producer Procurement (REIPPP) programme, which started in 2011, is widely considered the continent’s leader and pioneer.

‘The REIPPP model has translated into significant benefits for South Africa and its successes can be easily replicated in other industries and in other countries,’ according to Mpho Mokwele, head of project finance for the DBSA, which to date has invested ZAR13 billion into its projects.

‘Governments have recognised the need to work together with the private sector to achieve the stated objectives and there are strong indications to suggest that there has been wider adoption of private sector investment in the energy sector in various countries.’

From an investor’s perspective, he says, several criteria have been crucial to the success of the REIPPP. ‘Clarity around the legal and regulatory framework and a transparent, competitive procurement regime have been essential in providing certainty around the procurement process and sanctity of contracts.

‘From a project bankability perspective, the fundamentals based on the due diligence of the projects need to be sound. In addition, the sustainability imperatives embedded in projects enable them to achieve both delivery of the required megawatts and socio-economic objectives,’ he says. ‘The investor base includes both debt and equity investors and has also matured over time. We’ve seen participation from institutional investors as the profile of the projects is well suited to their long-term investment horizon and objectives.’

Meanwhile, the IRP Govender refers to is intended to be a two-year rolling ‘least cost’ plan that predicts energy demand across a 20-year period and lays out government’s choices in terms of energy ‘mix’. Prior to 2018, the last IRP was the 2010 iteration. ‘This should have been updated every two years, but that was never done,’ she says.

This changed in August when Jeff Radebe, South Africa’s Minister of Energy, released a draft update of the IRP. The headline news was that it dumped former President Jacob Zuma’s plans for nuclear energy entirely and saw a reduction of the projection for coal-burning power in favour of renewables. By 2030, if the IRP is realised in its present form, coal will account for just 46% of South Africa’s energy generation (significantly down from 85.7% in 2016), while gas will increase to 16%, wind to 15% and solar PV to 10%.

Govender argues that it is critical these figures are not seen as set in stone, and that regular two-yearly reviews and updates actually happen. ‘A slight change concerning the assumptions can alter the path chosen.’ While she says there are still important gaps in South Africa’s regulatory framework, ‘the IRP update unlocks momentum for energy generation and holds promise for the road ahead’.

Financiers have been waiting for this clarity for some time. Prior to 2015, the REIPPP programme had leveraged some ZAR194.1 billion investment, the bulk of it from domestic funding sources, through 102 projects. Yet in 2015, cash-strapped South African power utility Eskom baulked at signing any more power purchase agreements, leaving 27 projects, valued at ZAR55.92 million, stranded.

The logjam was unblocked in April when Radebe announced that the outstanding agreements would be signed. By the end of July, the outstanding projects had reached financial closure. But there now appears to be a period of inactivity looming. ‘The IRP suggests commissioning a new renewables generating plant only in 2025,’ says Govender. Working back from that date, she argues, procurement will not start before 2021. ‘That leaves a lull in project activity,’ she says. This is the South African programme’s next challenge – smoothing procurement so these sorts of gaps do not occur.

South Africa certainly suffered reputational damage during the 2015 to 2018 hiatus in energy procurement.

Radebe’s initiatives have gone some way towards recovering lost ground. This is why the commitment of his government to a ZAR400 billion infrastructure fund, announced in September, holds much potential. It is less a matter of the aggregate sum involved than the renewed commitment to the well-established infrastructure-led growth path.

South Africa’s President Cyril Ramaphosa is clearly hoping to open new sources of finance, including the sovereign wealth funds he has interacted with in recent months. He has spoken of the parallel with the Fifa 2010 World Cup, where South Africa delivered not only the new stadiums but also roads, infrastructure, urban renewal programmes and the first phase of the bus rapid transit system in major cities. But the difference is that 2010 was predominantly about on-budget government spending.

The question this time around is whether the private sector will come to the party. The pattern of renewable energy investment in sub-Saharan Africa suggests that it is important to the continent that South Africa gets this right.