These days, eco-aware architecture is well established: new developments compete for green-building ratings, and energy and water efficiency are high on clients’ wish lists. Yet most buildings, in African cities and globally, were built before such ecological concerns were widespread. These structures remain intact, stamping their large carbon footprint on the urban landscape.

The list of problems inherent in ageing building stock is long. Older structures are often energy-wasteful, with inefficient heating or cooling due to poor building materials or insulation. Leaking pipes and old fittings cause water wastage and, often, old buildings need more intensive maintenance. Elderly buildings can also contain hazardous materials no longer used in construction, such as asbestos, mercury and lead – putting their occupants’ health at risk.

Chlorofluorocarbons and hydrochlorofluorocarbons are commonly found in refrigerants in older heating, ventilation and air conditioning (HVAC) systems – worldwide, these have been discontinued due to their contribution to ozone depletion. What should we do with these inefficient and, in some cases, toxic remnants of a less conscious era? Why not simply knock down the problematic vintage structures and build anew? New buildings have a huge ecological impact if you factor in the demolition of the previous structure, site clearing and the manufacture and transportation of building materials. According to Candice Manning, sustainability practice area lead at AECOM, studies show that it may take between 10 and 80 years for a new, energy-efficient building to counteract the negative environmental impacts of its construction.

The basic structure of an older building might in some cases be more environmentally sound than what would replace it. If the building is built with good architectural design principles, says AECOM professional architect Aneli Steyn, in terms of ‘wall density, spatial design, wall-to-window ratios, roof overhangs, building orientation and so on, then it is not only economically more efficient to upgrade but also more effective in terms of green building’. She points out that in a lot of ‘flashy’ modern architecture, basic energy-saving principles can be forgotten. ‘It’s all about glass facades and building shapes. We tend to design systems to compensate […] but if we weigh the odds on new build versus refurbishment of existing, an existing refurb is far more effective from an environmental and economic perspective.’

The only time a full demolition would be recommended is if there are hazardous materials on-site that cannot be removed any other way. ‘The structural integrity and use of unsafe materials play a major part in establishing whether it would be suitable to reuse,’ says Marli Swanepoel, candidate architect at Paragon. If portions of a building must be demolished, then the materials should ideally be reused.

In any event, demolition is an expensive solution; not favoured in the current economic climate. As Manning explains, internationally, old buildings are being replaced at a rate of just 1% to 3% per year – so existing buildings will still be here in 15 to 20 years. This is true of South Africa too. Looking at key economic hubs, such as Sandton, ‘commercial office space is sitting at vacancy rates in excess of 15.9%’, says Alison Groves, regional director of building services at WSP in Africa. ‘There is an excess of available office space and, as a result, there likely won’t be many new buildings being built in the short- to medium-term. New building projects represent only a very small portion of the entire built stock.’

There are also socio-economic reasons to encourage intensive renovation of the built environment. South African cities experience a constant influx of immigrants from other countries and from rural areas. ‘If we keep encouraging sprawl and building outside our cities instead of improving what we already have, we are going to create serious environmental problems and greater resource challenges than what we are already experiencing,’ says Manning.

In short, as sustainability consultant Catherine Luyt puts it, demolition should be a last resort. ‘The best thing one can do for the environment is not build at all. However, that is unrealistic, so those that are already built should be retrofitted, altered and reused as far as possible.’ There are many ways to refurbish a building to make it greener. Recycled materials can be used to reduce the embodied carbon of the development. Energy efficiency can be improved with the use of natural light, efficient light fittings and smart switching. Temperature and air flow can be manipulated. And building occupants can practise more sustainable day-to-day management.

The good news for building owners is that basic green retrofits – such as installing low-flow taps, motion-sensitive LED lighting and CO2 monitors – are relatively inexpensive and can produce significant savings. ‘Applying simple passive heating and cooling principles can improve an existing building’s airtightness, indoor environmental comfort and thermal heat gain,’ says Swanepoel.

More costly retrofits may include upgrading glazing and installing efficient, modern HVAC, greywater and renewable energy systems. But these measures will eventually pay for themselves in reduced operating costs. ‘Installed correctly, systems and structures can produce a sustainable return on investment,’ says Groves. Green buildings ‘offer significant value adds to savvy users’.

Greener buildings also mean higher rentals and increased property values. According to Grahame Cruickshanks, managing executive of market engagement at the Green Building Council of South Africa (GBCSA), renovated buildings attract ‘environmentally aware tenants who want to have a lighter impact on their environment, and who are willing to pay an increased rental to ensure this’.

There are interpersonal benefits too. Green buildings are healthier spaces, leading to reduced staff turnover and greater productivity, for the entire lifespan of the building. Tenants, Cruikshanks confirms, are willing to pay more for ‘a green interior that is healthy and invigorating to work in, as opposed to a deep, dark building with no natural lighting and little natural air flow’.

Rudolf Pienaar, Growthpoint’s chief development and investment officer, agrees. ‘All major, responsible companies demand a green building when considering their workspace, and it is these quality companies that make the most desirable tenants.’ Cruikshanks’ organisation, the GBCSA, with its Green Star rating system, is an influential force in local building development. Its Existing Building Performance (EBP) tool enables South African building owners to acquire green credentials without the hefty expense of a new build. ‘While many new green buildings are changing the skylines of South Africa’s cities, helping existing buildings tread lighter on their general natural environment is crucial to the work of the GBCSA,’ says Cruikshanks.

Developers can also use the EBP tool to assess the success of their refurbishments. It provides ‘a solid metric to measure the success of the interventions and justify the capital investment’, says Groves. Notable South African examples of retrofitted buildings with Green Star certification include the buildings in the high-profile Silo District of Cape Town’s Waterfont; Black River Park in Observatory (where the ‘north park’ became the first building in the country to be awarded an EBP certification); and WWF South Africa’s refurbished building in Braamfontein (which achieved 6-star Green Star status, the highest GBCSA rating available). ‘These buildings are exactly what businesses want,’ says Pienaar, speaking of the many retrofitted buildings in Growthpoint’s in-demand Thrive portfolio.

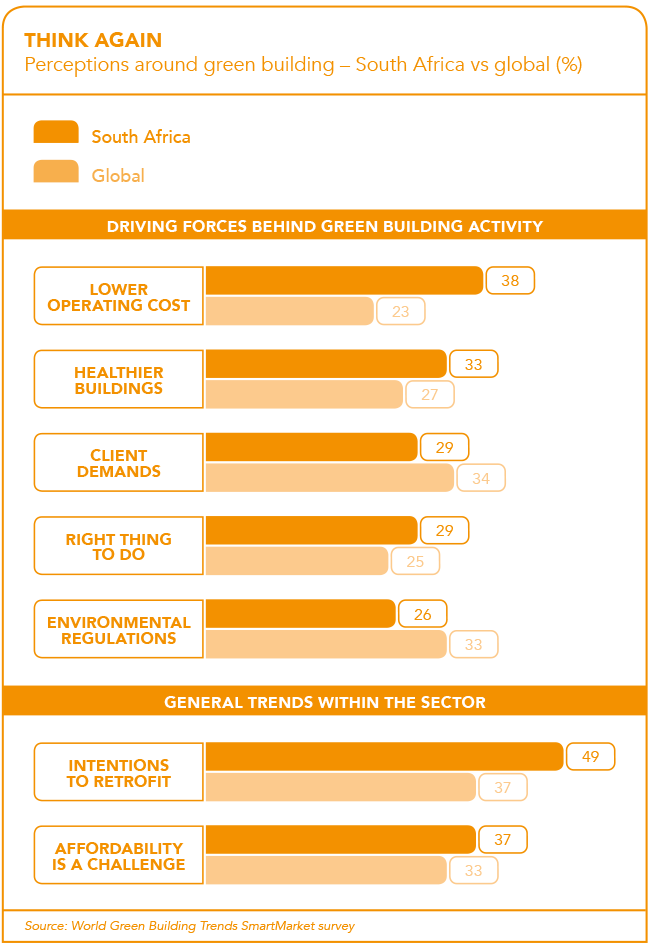

The green renovation trend can only strengthen. The World Green Building Council is pushing for 100% net zero carbon buildings (which have no greenhouse gases) by 2050, including older builds. To meet that global goal, African countries must aim to modify as many existing buildings as possible. South African developers appear to be on board. The World Green Building Trends SmartMarket 2018 report notes that retrofitting existing buildings has become South Africa’s biggest green building sector, widely expected to form a large part of the industry’s ongoing work.

We can’t predict all the effects of climate change, nor all the technological developments that may bring further efficiencies to construction. Luyt points to improvements to HVAC systems, as well as regenerative elevator drives (which generate power to feed back into the building’s grid), as promising examples of recent innovations.

The gleaming green buildings being built today may well be in need of retrofitting tomorrow – in ways we may not yet even have thought of. All we can be fairly sure of is – in the words of architect Carl Elefante, quoted by Swanepoel, is that ‘the greenest building is the one that is already built’.