Africa’s green building sector has discovered the virtues of perlite – a naturally occurring volcanic glass that has been used as a sustainable insulation material and partial cement replacement in the US, Europe and the Middle East for decades. Other sustainable building materials making inroads locally include self-sealing concrete for waterproofing, high-performance glass that reduces the need for heating and air conditioning, as well as bio-composites such as hempcrete, which combines hemp, lime and water in a construction and insulation material that is hard as stone but at the same time more flexible and lighter than concrete.

Another trend has seen materials given a new life through recycling (such as using regenerated polystyrene in concrete bricks), or through innovative processes such as glulam (glued and laminated) timber, which is an engineered wood product that is stronger than solid timber, comparable to steel in strength but much lighter (and with a significantly smaller environmental footprint).

‘The future is already here,’ says Alison Groves, WSP director of building services for the Africa region, adding that the new generation of seemingly futuristic, more sustainable building materials is not a gimmick but a reality. ‘I can see applications for highly innovative alternative materials and methods but it still takes a brave client or architect to commission them in Africa,’ she says, and explains that for one, there’s a lack of trust in untested, uncommonly used materials, especially for large commercial projects. Building professionals are reluctant to put their reputation on the line for something unfamiliar to them, and it takes time to build local skills for the application of new materials.

‘Another issue is finance and insurance, because for bank-bonded buildings, it’s unlikely that alternative materials or techniques are allowed,’ says Groves. ‘Often the cost versus the benefit is not yet clearly understood. But where we’re seeing an expansion into more alternative materials is in the private residential house and small-business sector outside the urban areas.’

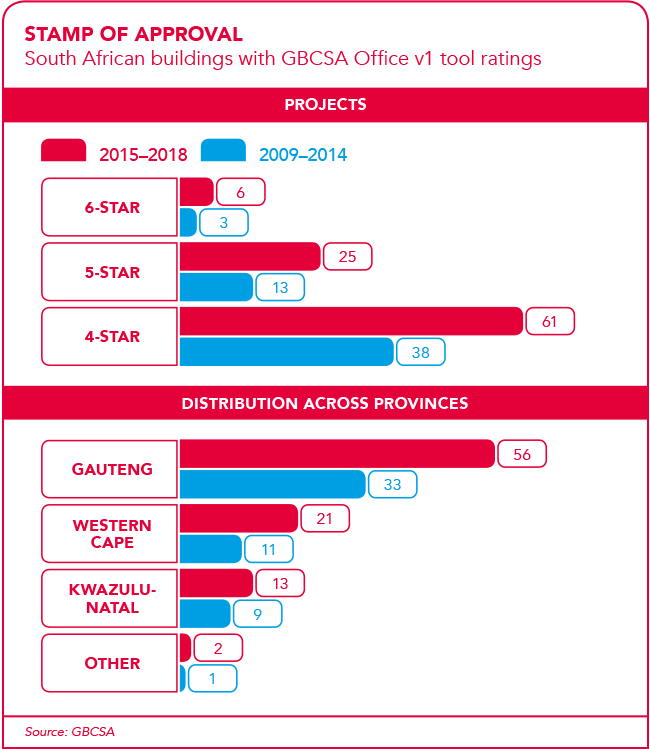

Materials is one of nine categories assessed in the Green Building Council of South Africa’s (GBCSA) Green Star rating tool, which has been adapted for the ‘local context’ of a growing number of African nations, including Kenya, Namibia, Mauritius, Rwanda, Nigeria, Tanzania, Uganda and Ghana.

‘I believe the choice of materials is important for the overall sustainability of a building,’ says Marloes Reinink, founder and director at Solid Green, a South Africa-based green building consulting firm that is extending its reach into Africa (and has worked on Green Star projects in Botswana, Namibia, Mauritius, Ghana and Kenya). ‘Materials have quite an energy-intensive footprint in their manufacture,’ she says. ‘With the newer buildings using less and less energy, the embodied energy of materials starts to play a larger role if you look at the total carbon footprint of the building.

‘In Green Star it is fairly well defined what you need to focus on in terms of materials, such as: reduce cement content in concrete; or increase recycled content in steel; use sustainable certified timber; encourage reuse of materials; and use local materials.’

That’s where alternative materials such as perlite come in. It can be used as an aggregate replacement in cement. ‘Reducing the cement content in concrete is an effective way of tackling the embodied carbon in building materials, as it significantly cuts down the CO2 emissions,’ says Groves. She explains that in South Africa, fly ash (a waste product from coal production), volcanic ash and GGBS (ground granulated blast-furnace slag, which is a waste product from steel manufacturing), are already widely used as cement replacements.

‘We also use Pratliperl, which is a perlite mixture that’s blended into cement and can be used to produce an incredibly strong, light-weight concrete slab that is fire-resistant and has good thermal and acoustic properties,’ she says. ‘The end product is much stronger and costs less than Portland cement, but it takes up to a week to dry, which extends your build time.’

One of the GBCSA member organisations, CemteQ, produces a range of smart sustainable building materials in South Africa that incorporates perlite. ‘Not only does exfoliated perlite meet “green” criteria but it is also inorganic, non-combustible, odourless and durable, pH-neutral and has a very low carbon footprint,’ states CemteQ online. ‘It is a relatively inexpensive and practically untapped raw material, with less than 1% of the global reserve base having been mined. No chemicals are used in processing perlite, it is chemically inert and no by-products are produced. Perlite has excellent insulating qualities with long-term savings in energy consumption when used as an aggregate replacement in concrete, plaster and screed. It is also used in various precast building products, making them lighter and easier to transport.’

The material has, for example, been used to create a lightweight concrete floor for the new Woodmead, Johannesburg headquarters of IT firm Oracle, which recently moved into the 4-star Green Star-rated office building.

Self-sealing, permanently waterproof concrete, based on crystalline technology is another 21st-century material that has come to South Africa. Canadian chemical firm Xypex says it developed this technology more than 40 years ago, using chemicals to penetrate the capillary tracts in concrete and (when exposed to moisture) form a new non-soluble crystalline structure. Penetron is another manufacturer of locally available, crystalline waterproofing products. ‘The crystals grow within the concrete as moisture occurs, allowing cracks and pores to “self-seal” and become waterproof,’ says Groves. The technology is being used worldwide to enhance the durability and lifespan of concrete in bridges, tunnels, harbours, swimming pools, power stations and any kind of foundation.

In the Western Cape, Xypex products have been used in the Daimler Chrysler machine room in Atlantis, and to waterproof undersea tunnels, lift shafts and pools at the One&Only Hotel, V&A Waterfront. Meanwhile Penetron announced that one of its products had been mixed into the concrete (during batching) to build all the retaining walls and exposed concrete at the massive Teraco Data Centre in Isando, Johannesburg. Penetron was also successfully used for the Vodafone Site Solution Innovation Centre in Midrand, the country’s first 6-star Green Star-accredited building.

It’s worth noting that the GBCSA doesn’t ‘test, review or certify’ products or materials; only building projects. It relies on ‘credible, third-party certification bodies as and when such bodies are formed’, states the council, which has endorsed Ecospecifier Global GreenTag and Ecostandard South Africa.

The growing focus on indoor air quality and green fit-out materials has brought attention to occupant health and productivity. ‘The impact of airborne chemicals in the indoor environment, such as volatile organic compounds [VOCs], is understood to cause a range of adverse health effects, including ear, nose and throat irritation, nausea and headaches,’ according to Green Cape’s Green Building Material Catalogue, which advocates VOC minimisation and enhanced ventilation inside homes, schools and workplaces.

The Living Building Challenge (LBC), a rigorous holistic green building-certification programme, also takes these factors into consideration. Reinink, who is the global challenge’s first ambassador for South Africa and involved in two residential ‘full living buildings’ in Cape Town, explains. ‘In LBC, the project will have to calculate the total embodied energy of the complete building, including all materials, and once it is calculated, the total amount of carbon must be offset through a carbon offset scheme. So if you choose materials with a high carbon footprint, such as aluminium, cement and so on, then you pay more to offset that carbon.

‘Beyond that the LBC focuses on local materials as well, and it also provides a “red list” of materials that cannot be used in the building as they have demonstrated they are either bad for your health or damaging to the environment, such as PVC, VOC, formaldehyde and 20 others.’

Locally, Belgotex is a leader in green fit-out materials and South Africa’s first flooring manufacturer with the Global GreenTag eco-label certification. The company also has a 6-star Green Star-rated factory in Pietermaritzburg that produces carpets that include eco-friendly ranges made from repelletised post-production waste (a blend of polypropylene and recycled eco fibre). Many of Belgotex’s fibres and yarns are created in dry processes that save water, chemicals and energy consumption.

While it’s still nearly impossible to source local materials that don’t contain any chemicals from the Red List, schemes such as the LBC are encouraging discussions about toxic content and embodied carbon in building materials in Africa. And again, it’s the big picture that matters: the green credentials of a material throughout its life cycle – from production, transport and construction to its performance during the operation of the building and, eventually, the way it can be recycled when the building is no longer needed.