When Africa’s most advanced nanosatellite was launched into space, the team of South African students who developed and built the tiny device followed its journey through a live video link from Siberia, Russia. ‘We all got together in the labs very early on 27 December 2018, as the launch was around 4 am local time here in South Africa,’ says Robert van Zyl, who heads the French South African Institute of Technology (F’SATI) and is also director of the Africa Space Innovation Centre at the Cape Peninsula University of Technology (CPUT).

‘We were elated when the rocket launched. Later that day, when the satellite passed over Cape Town, its first signals were received at our ground station and the SpaceTeq ground station near Grabouw. That caused huge celebrations, because then we knew the satellite was successfully deployed in space and is indeed alive.’

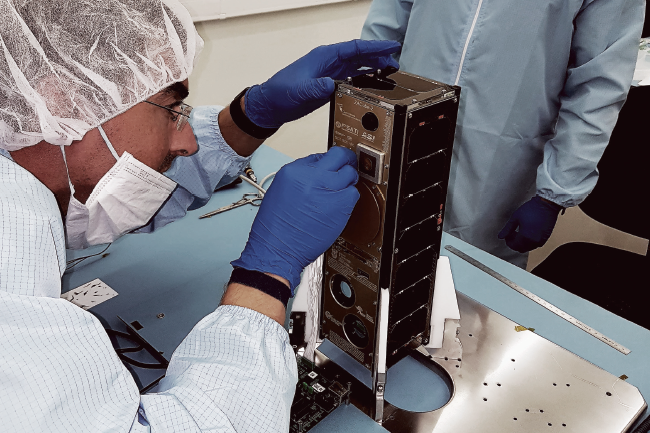

Nanosatellites weigh between 1 kg and 10 kg and often take the shape of ‘cube’ satellites. They are valuable tools for research and training the next generation of space engineers, mainly because they are significantly more affordable than big satellites. CubeSats cost a fraction to build and launch, as they use off-the-shelf components and can piggyback as an auxiliary payload on a larger space mission.

CPUT’s newest satellite, ZACube-2 – developed with F’SATI – is a technology demonstrator for the Maritime Domain Awareness satellite (MDASat) programme – a constellation of nine nanosatellites that will provide cutting-edge remote sensing and communication services to the oceans industry. ZACube-2 helps to monitor shipping traffic along the South African coastline through its primary payload – an automatic identification system (AIS) receptor, which is the maritime equivalent of air traffic control. The secondary payload is an experimental camera (‘K-line imager’) designed by the Centre for Scientific and Industrial Research to detect veld fires in order to improve emergency response times.

The entire satellite weighs just 4 kg and follows its even tinier predecessor, ZACube-1, known as TshepisoSat, which weighed 1 kg and was smaller than a loaf of bread. CPUT students spent 60 000 hours developing and building the device that was launched into space for weather research in 2013. ‘TshepisoSat is still alive and communicates with us through our ground station,’ says Van Zyl. ‘It‘s remarkable that the radio, which we developed in-house, is still working after so many years. All the data and telemetry over the past few years can now be mined to characterise the space environment, validating our thermal and structural models, and studying the effect of radiation on the electronics and imager, to mention but a few. The satellite will de-orbit in about 10 years’ time.’

The CPUT team and its partners will take the learnings from ZACube-2 to develop three nanosatellites for the MDASat programme. ‘So far the payload is behaving very well, but further refinements will be made for the three MDASat satellites,‘ says Van Zyl. The launch of ZACube-2 was a milestone towards becoming a key player in the ‘innovative utilisation of space science and technology’, said South Africa’s Minister of Science and Technology, Mmamoloko Kubayi-Ngubane, at the time. ‘Science is indeed helping us resolve the challenges of our society. I am particularly excited that the satellite was developed by some of our youngest and brightest minds under a programme representing our diversity, in particular black students and young women.’

The South African National Space Agency (SANSA) echoed this sentiment by inscribing ZACube-2’s nadir panel with the words: ‘To journey beyond conventional knowledge with the intent to discover what is unknown is the highest ambition of mankind. This satellite, though little, carries the passion and ingenuity of South Africa’s young scientists, technicians and engineers in such a pursuit.’

For Africa, national space programmes shouldn’t be seen as wasteful vanity projects but rather as a push towards participation in the global space economy. ‘We contribute directly to the democratisation of space, which is of course dependent on a sovereign capability to develop and use space for the socio-economic development of South Africa and the continent,’ says Van Zyl. For example, there are numerous benefits to owning satellite technology over having to pay for the use of imagery from other nations. Having near real-time access to local satellite data enables nations to monitor and protect against disasters (such as floods, drought or wildfires); manage their natural resources (by tracking mining activities or bodies of water); and boost food security (through crop monitoring). Other uses include the mapping of human settlements and the provision of broadband communication services.

Then there’s the business angle, as nations can earn hard currency by commercially designing and manufacturing space-related technology, satellites, parts and services. Space companies in South Africa include Space Commercial Services; NewSpace Systems; CPUT’s newly formed Amaya Space; and Stellenbosch University’s company CubeSpace.

And then there’s space travel: South African entrepreneur Mark Shuttleworth was the continent’s first private ‘space tourist’ in 2002, but now Nigeria wants to become the first African nation to send an astronaut on a space mission by 2030. This may be ambitious but it shows Africa’s urgency to increase its stake in the world’s space economy, which was valued at US$329 billion in 2016, according to the US-based Space Foundation. The continent’s largest players are Nigeria and South Africa, followed by Algeria, Angola and Egypt, and lately also Morocco, Ethiopia, Ghana, Kenya and Rwanda. The latter, in a partnership with Japan, is about to launch its first locally developed satellite – a telecoms satellite –from the International Space Station. Japan has also supported Ghana to send its first satellite, a US$500 000 CubeSat developed by students, into space in July 2017. Kenya launched its first satellite in May 2018. Also a CubeSat, it was built by the University of Nairobi for use in weather forecasting and food-security mapping.

The AU has established an African Space Agency, which intends to implement space policy and strengthen African space missions and capabilities. In February 2019, Egypt emerged as host country for the agency headquarters. Around the same time, Egypt sent its third Earth observation satellite – EgyptSat-A – into orbit onboard a Russian Soyuz rocket. It was jointly built with a Russian contractor at a cost of about US$100 million.

Ethiopia, which also bid to host the space agency, recently built its own multimillion-dollar space observatory and research centre in Addis Ababa. The Horn of Africa nation intends to launch its first satellite in September 2019, backed by Chinese funding. The US$8 million satellite will be used to monitor climate change and weather phenomena.

In January 2019, meanwhile, SANSA was named as the continent’s designated regional provider for space weather information by the International Civil Aviation Organisation. ‘This means that every aircraft flying in the continent’s airspace will rely on SANSA for the space weather information it needs to submit as part of its flight plan,’ according to Kubayi-Ngubane. ‘Space weather can lead to reduced signals from global navigation satellite systems, adversely affecting navigation, increased radiation, which can destroy human cells and tissue, especially during long-haul flights, and blackouts of high-frequency radio communications, which are critically important for the aviation and marine sectors.’

South Africa also made headlines six months earlier, as it inaugurated its ZAR4.4 billion, 64-dish MeerKAT telescope in the Northern Cape province. The powerful radio telescope has produced the best image ever taken of the Milky Way galaxy, clearly revealing the massive black hole at its centre. The global Breakthrough Listen initiative, which seeks signs of intelligent life in the universe, will incorporate MeerKAT in its existing search for any indication of extraterrestrial technology. In addition the telescope will eventually become part of the Square Kilometre Array (SKA), the mega-science project that has involved 100 organisations from 20 countries in its design and development. Currently building Phase 1, SKA is expected to enter Phase 2 by 2023, with the construction of out-stations in eight African partner countries (Botswana, Ghana, Kenya, Madagascar, Mauritius, Mozambique, Namibia and Zambia). The telescope will be 50 to 100 times more sensitive than any other radio telescope developed and will help scientists further unlock the mysteries of dark matter and black holes.

These investments have sparked global interest in Africa’s space capabilities. While the continent’s space development has a way to go, the future looks promising as global space experts prepare to flock to Cape Town for the 2020 Space Ops. For the first time, the conference will be held on African soil, putting the continent firmly on the world radar.