The numbers are staggering. A recent McAfee report puts the global cost at US$600 billion, or about 0.8% of global GDP. That’s up – significantly so – from just four years ago, when the same analysis put the cost at US$500 billion. But the numbers don’t stop there: in PwC’s Global Economic Crime and Fraud Survey 2018, 41% of executives surveyed said that they’d spent at least twice as much on investigations and related interventions as was lost to cyber crime, while more than a third of the survey’s respondents said they’d been targeted by cyber attacks, through both malware and phishing.

Meanwhile, the recent IBM Cost of a Data Breach Report 2018 estimates the average global probability of a material breach (that is, a cybersecurity breach involving at least 1 000 lost or stolen records containing personal information) in the next 24 months to be 27.9%. South Africa, the report warns, had the highest probability among the countries and regions surveyed: an alarming 43%.

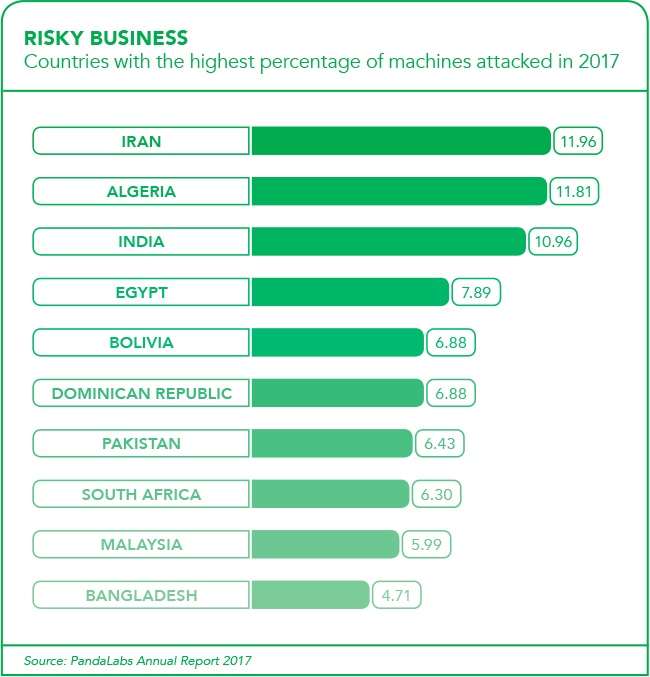

The reports, surveys, numbers and warnings grow bigger, scarier and louder by the day. Panda Security’s PandaLabs Annual Report 2017, published at the beginning of 2018, offers some measure of comfort when it says ‘entities that set aside more resources for security should receive fewer of these attacks, and indeed the figures show us just that. While home users and small businesses make up for 4.41% of attacks, in medium and large companies the figure drops to 2.41%’.

Yet the report goes on to say that, while this data can give companies peace of mind, ‘we should not allow ourselves to be fooled: attackers don’t need to attack all the computers in a corporate network to cause damage. In fact, they will attack the minimum number of possible computers to go unnoticed, and thus minimise the risk of detection and achieve their goal’.

This pervasive threat is forcing African businesses to rethink their approaches to cybersecurity – and to risk in general. ‘There is no question,’ says Simeon Tassev, MD and qualified security assessor at IT firm Galix Networking. ‘Cyber crime has pushed the awareness of cybersecurity and risk to the top of the pile, and along with it the need for a well-thought-out governance, risk and compliance [GRC] strategy. The escalation of cybersecurity threats over the past few years has shifted the way businesses view risk and the management thereof.

‘In addition, ransomware and other prevalent malware attacks have increased many business’ investments in cybersecurity solutions. However, with the impact of these threats extending beyond IT to affect business operations and tear at the value of data, it has also shone a spotlight on the way businesses manage their GRC strategies.’

Tassev explains that governance, enterprise risk management and regulatory compliance are elements that combine to form an organisation’s overall GRC strategy. ‘This strategy used to be regarded as a “nice to have”, but is now considered to underpin and align the enterprise’s IT, security and business strategies,’ he says. ‘GRC has traditionally been approached by most organisations as a tick-box exercise, though the rise in cyber crime has elevated the risk potential. Businesses consider cyber crime to be less of a potential threat to their business and more of a likely eventuality, meaning that their approach to GRC not only needs to take cybersecurity into account now, but also needs to be re-evaluated and updated more frequently than before.

‘In addition, the understanding of what is considered “acceptable risk” has shifted from annual risk monitoring and possible risk occurrence, to identifying real threats on their assets and operations, and planning accordingly.’

Tassev insists that businesses that do not have a solid GRC strategy, or that continue to view this as a simple tick-box exercise, are likely to be affected by cyber crime sooner or later – and IBM’s 43% figure underlines the inevitability of cybersecurity threats.

There is no guarantee against cyber crime, according to Tassev, but ‘having the right processes, policies, controls and supporting tools in place is the only way to guard against attack and reduce the risks’.

Graham Croock, director of IT advisory services at financial services firm BDO South Africa, agrees. ‘BDO does a lot of work in risk management,’ he says. ‘I’ve personally been involved in risk management for big, listed companies for about 20 years now. Cybersecurity is just another category in the overall risk register. You can’t look at cyber risk in isolation; you have to look at it in the context of overall risk.’

Croock says that BDO’s general advice to clients is to be prepared for the event. ‘Expect that you will have a cyber attack, and have first response teams ready and in place,’ he says. ‘It’s not a matter of if; it’s a matter of when it will happen – and how severe it will be. That talks to how dependent the client is on their systems. Some place more reliance on their systems than others, so we do a vulnerability assessment to understand where they are vulnerable, and how vulnerable they are.’

He emphasises that it’s not only tech companies who are at risk. ‘We’re living in a connected world, and it’s becoming more and more connected,’ he says. ‘Business is becoming global, and you can’t avoid technology. You’re not going to survive if you do. What you have to do then is become resilient, and be able to sustain the cyber attack when it happens.’

While it is obviously illegal to hold someone’s data hostage, what are the laws around paying the ransom? A recent report by the CyberEdge Group shows that most ransom-ware targets (about two-thirds of them) refuse to pay. But what about those who – out of desperation – do pay? According to Berné Burger, an associate, and Daniel Vale, a candidate attorney at Webber Wentzel: ‘There is no broadly applicable South African legal principle which makes ransom payments illegal. However, the broad duties set out in the Prevention and Combating of Corrupt Activities Act would also cover ransomware victims being obliged to report incidents of ransomware/extortion to the police.’

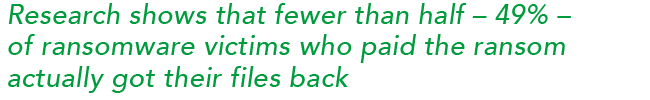

Burger and Vale are quick to point out that – legal issues aside – there are ‘many negative effects’ to paying the ransom. ‘For one, there is no guarantee that the hackers will return the hijacked data. And, secondly, paying a ransom not only emboldens current cyber criminals to target more organisations, but it also offers an incentive for other criminals to get involved in this type of illegal activity.’ They’re right. The CyberEdge Group report indicates that fewer than half (49%) of ransomware victims who paid the ransom actually got their files back. And that’s a key finding, held up against Symantec research that found the rate of ransomware infections continues to rise, with a sharp spike of 36% between 2015 and 2016.

Cybercrime takes many other forms, however, from malware and phishing to network scanning, brute force attacks and so on. In response to the sheer size of the problem, many organisations have deployed what’s now known as a security operations centre (SOC) to protect their critical data.

‘The SOC offers an attractive value proposition,’ according to Martin Potgieter, technical director at South African computer security company Nclose. He points out that instead of organisations making costly investments into individual cybersecurity solutions, ‘the SOC would unify all the disparate elements and create a single access point where all security-related information would be sent and processed for insights and ensure compliance to regulations and laws governing their industries’.

Unfortunately, adds Potgieter, many SOCs are purely compliance-driven initiatives. ‘Core to the problem is that too many organisations believe cybersecurity is simply a tech matter,’ he says. ‘Buy the correct mix of products and solutions, unify all the elements in the SOC, et voila! “My data is secure; come what may, I am protected from cyber crime”.’

Of course, it’s not that simple – which is why organisations in more developed markets are now moving to the managed detection and response (MDR) model, which provides 24/7 threat-monitoring, detection and response services through a combination of technologies, advanced analytics, threat intelligence and human expertise.

‘MDR’s distinguishing feature, however, is its focus on dedicated security engineers supported by machine-learning capabilities that provide real-time, continuous monitoring and threat detection,’ says Potgieter. ‘MDR craves information; it’s not limited by events-per-second, so costs are easier to control,’ he adds. ‘As human and machine learning capabilities work in concert to analyse data, organisations are far better placed to start developing trend analyses that can significantly reduce the number of false alerts, and make far better use of available resources.’

Here it’s worth returning to the McAfee report. The report authors found that the cost of cyber crime is unevenly distributed across the world, with variations by region, income levels and level of cybersecurity maturity. ‘Unsurprisingly, the richer the country, the greater its loss to cyber crime is likely to be,’ the report states.

But then comes the kicker – at least as far as Africa’s developing economies are concerned: ‘The relationship of the developing world to cyber crime is complex, as the mobile connections that have brought the internet to millions are easily exploitable, but the value that can be extracted from these connections remains relatively low, and weak defences in wealthier countries mean that is where criminals focus their attention. The countries with the greatest losses (as a percentage of national income) are in the mid-tier nations – those that are digitised but not yet fully capable in cybersecurity.’ As African businesses continue to enjoy the continent-wide technological ‘leapfrogging’, it’s well worth paying attention to this warning.