In early June, Vietnam’s internet went down. Well, not entirely… but there were widespread outages, and the country’s connection was definitely slower than usual. The problem lay under the South China Sea, about 130 km off the coast of Da Nang, in a broken power supply unit on one of the submarine cables that connects Vietnam to the Asia Pacific Gateway communications system. As local internet service providers scrambled to reroute the South-East Asian country’s internet traffic to alternative cable lines, tech players across the world had flashbacks to 2008, when a series of mishaps –believed to be anything from ship anchors to earthquakes to sabotage – saw five major undersea cables in the Mediterranean Sea and Red Sea being cut, disrupting internet access from Egypt to India.

Those undersea cables are absolutely vital to the modern world’s internet-driven economy. Years ago, the wheels of commerce moved overland or along ocean-bound trade routes; today, commerce happens via nearly 400 thick cables that run along the seabed, crossing oceans, connecting continents and delivering hundreds of terabytes of information across thousands of kilometres in fractions of seconds.

South Africa, for example, gets most of its internet connectivity via the SEACOM network, which links to the five largest exchange points in Europe (London, Frankfurt, Amsterdam, Stockholm and Marseille), as well as Mumbai in India. As data demand continues to increase, SEACOM has extended its Southern African footprint, recently adding six new points of presence (PoPs) and more than 60 network nodes through its acquisition of FibreCo.

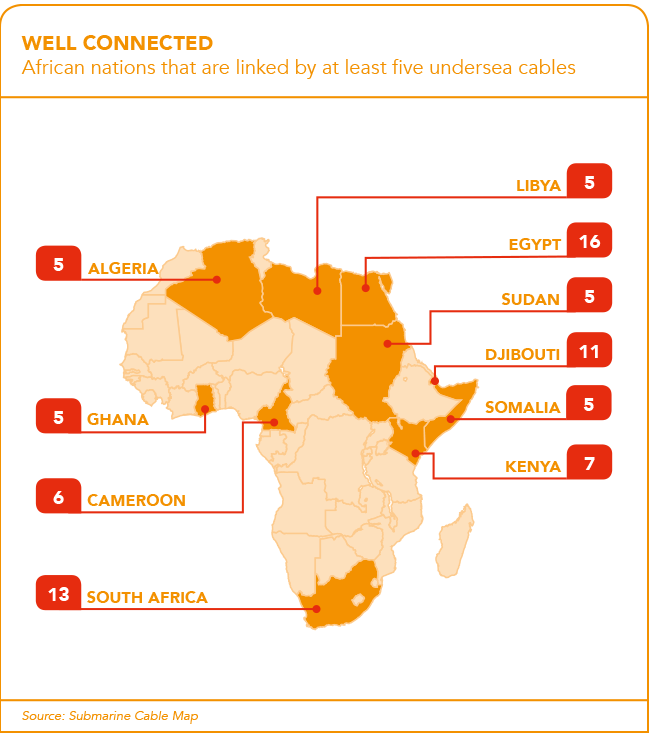

Much of the growth has been driven by the continent’s massive new data centres (DCs) – including the first Microsoft Azure DCs in Johannesburg and Cape Town, and Mombasa’s new Icolo DC – and by advances in cloud computing. Yet, as internet users in Vietnam (or Egypt, India, or anywhere else) will tell you, it’s risky business relying on a single network (or a single cable) to keep your region connected to the global internet. After all, submarine cables are tough, but not indestructible. All it takes is a seismic event here or an errant ship’s anchor there to cut the connection. While that sort of thing goes relatively unnoticed in the northern hemisphere (Europe and North America, for example, are linked by 19 underwater cables), there simply aren’t as many alternative options in Africa. That risk has created a gap in the market for alternative infrastructure solutions.

However, risk is only part of the picture. Long cables create latency issues; the shorter the distance your information has to travel, the less time it’ll take to reach its destination. That’s why Finnish cable operator Cinia and Russian telecoms operator MegaFon recently announced plans to lay a submarine fibre-optic cable across the Arctic Ocean, taking a North Pole shortcut to link Europe, Asia and North America. Their plan would cut the cable distance between Europe and North America’s west coast by as much as 30%.

Other operators are looking to cut the cable distances (and increase the cable options) to, from and within Africa. Kenya is currently working on connecting to the Djibouti Africa Regional Express (DARE) submarine fibre-optic cable system. The US$59 million project, scheduled for completion by June 2020, will extend 4 747 km and provide 36 terabytes per second of capacity to East Africa.

Meanwhile, the Telegraph and the Wall Street Journal (WSJ) reported recently that Facebook plans to lay a submarine data cable around the continent, aiming to drive down its bandwidth costs and make it easier for African users to sign up for the social media giant’s platform. While Facebook spokesperson Travis Reed wouldn’t confirm or deny anything (‘We look all over the world when we consider subsea cable routes,’ he told the WSJ), the Telegraph quoted Nunu Ntshingila-Njeke, Facebook’s head of Africa, as saying that: ‘At Facebook, we have a saying that we’re only one percent done, and this couldn’t be truer for Facebook in Africa.’ It couldn’t: fewer than 13% of Africans use Facebook, and Facebook has no data centres in Africa.

With the company facing market saturation in its Western markets, it is naturally looking for new opportunities – and Africa looks like a particularly prime opportunity. Details remain sketchy, but Facebook’s planned project – codenamed Simba – is believed to be a three-stage undersea cable ring around the continent, which might link to existing coastal access along North, West and East Africa.

Chinese telecoms giant Huawei is also believed to be looking to Africa for growth, despite – or because of – pressure from the US government, amid allegations of espionage. Huawei recently announced the sale of its majority stake in undersea cable business Huawei Marine, after having been involved in 90 submarine cable projects stretching over more than 50 000 km. One of those projects was a 2015 upgrade to a cable linking South Africa with the UK, initially built by former telecoms firm Alcatel-Lucent. Other projects included a transatlantic cable linking Brazil and Cameroon.

Elsewhere, Angola Cables’ new South Atlantic Cable System (SACS) went online in late 2018, providing a low-latency connection between Africa and the Americas through its direct link between Angola and Brazil. Crucially, the cable cuts out the need for that transatlantic data to travel halfway across the world via Europe. The SACS offers data transfer speeds five times faster than existing cable routings, cutting latency between Luanda and Brazil’s Fortaleza from 350 milliseconds (ms) to just 63; and connecting Luanda to London and Miami with approximately 128 ms latency. The onward connections to the Monet cable and the West Africa Cable System (WACS) mean that latency between Cape Town and Miami can also be reduced from 338 ms to 163 ms.

‘Our ambition is to transport South American and Asian data packets via our African hub using SACS and, together with Monet and the WACS, provide a more efficient direct connectivity option between North, Central and South America onto Africa, Europe and Asia,’ says Angola Cables CEO António Nunes. ‘By developing and connecting ecosystems that allow for local IP traffic to be exchanged locally and regionally, the efficiency of networks that are serving the southern hemisphere can be vastly improved. As these developments progress, they will have considerable impact for the future growth and configuration of the global internet.’

The next step, of course, is to link those high-speed submarine cables from their coastal PoPs to Africa’s vast interior. This is a key growth area for the likes of SEACOM, as well as for Angola Cables. Indeed, last year Angola Cables signed an MoU with Broadband Infraco, which will link their underwater cables to Broadband Infraco’s 156 PoPs and more than 14 960 km of South African fibre networks. ‘The very real possibility now exists to connect Brazil and South Africa to the other BRICS nations of Russia, India and China through a high speed, low latency connection,’ says Nunes. ‘Such a connection together with our robust network will accelerate international co-operation on multiple levels, promote economic development and fast-track projects that will enable new opportunities for digital content exchange across the region.’

That, ultimately, is the goal: to link the continent’s inland commercial hubs – Johannesburg, Nairobi, Kigali, Kinshasa, Addis Ababa and others – to the rest of the world via reliable, high-speed internet connections. The key links in those chains lie along the coast, though, and in the growing number of submarine cables that act as Africa’s modern trade routes.