When you need water, you turn on a tap and fill your glass with municipal water. When you want a light on in your room, you flick a switch and connect to the power grid. When you want to connect to the internet… Well, that’s where things get complicated. Because while some African cities – notably Tshwane, in South Africa’s Gauteng province – offer free public WiFi, most don’t. Yet, increasingly, WiFi connectivity is starting to look much more like a utility than a nice-to-have.

Provider Ruckus Wireless estimates that there are four times as many devices connected to WiFi as there are to mobile or cellular data networks. In the modern, hyper-connected age, it’s no longer regarded as a crazy idea when it’s suggested that internet access should be as widely available as water or electricity.

‘Looking into 2018, we believe the state of the WiFi industry continues to look positive,’ says Riaan Graham, sales director of Ruckus sub-Saharan Africa. ‘The bottom line is that WiFi is the perfect solution for the data challenges that are coming from a worldwide infatuation with, and insatiable demand for, more and better wireless data services of all types.’ WiFi is ‘a utility certainly worth the investment’, he adds.

In an opinion piece on Bizcommunity, Hero Telecoms executive chairman Alan Knott-Craig takes it a step further, arguing that WiFi now ‘props up Maslow’s hierarchy of needs’. He isn’t kidding. ‘There’s no point in arguing it,’ he writes. ‘It just is. WiFi has become a basic human need.’ Knott-Craig adds that the demand for WiFi (as opposed to 3G or fibre) is driven by the perception that WiFi is free. ‘People don’t just want internet access. They want free internet access.’

Knott-Craig likens the future of data to the history of water. ‘The market will be split between Perrier (fibre), bottled water (3G) and tap water (WiFi). The Perrier and bottled water will be expensive. Too expensive for most. The WiFi will be free,’ he writes.

Of course, there’s no such thing as free anything. Someone, somewhere along the line, will have to pay for that WiFi. But, Knott-Craig insists, that someone won’t be the user. ‘Public, free WiFi networks are already being cross-subsidised. Think of your local coffee shop. You most likely get free WiFi there. Who pays? The coffee-shop owner. She has done the math that the cost of paying for WiFi on behalf of her customers is outweighed by the additional revenues generated by attracting and retaining her clientele. Eventually, shopping centres will get their heads around this.’

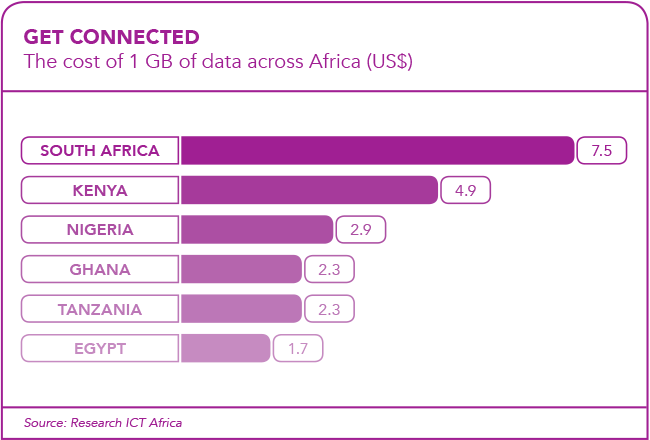

In Tshwane, the local government already has. There, the city offers more than 1 000 free internet zones, which provide nearly 2 million citizens access to free WiFi under the ‘TshWi-Fi’ banner. Speaking at the Gauteng Technology Innovation Conference in February, South Africa’s Minister of Telecommunications and Postal Services Siyabonga Cwele said that he wants to see more of these free, public WiFi hotspots being rolled out across the country. Cwele sees them as key to addressing issues of inequity for the communities that can’t afford the country’s notoriously high data costs. ‘We need to scale up these public WiFi programmes,’ he said. ‘We need to work with our mayors to ensure these programmes are scaled up.’

In South Africa, Tshwane’s free WiFi roll-out is regarded as the gold standard. ‘The high profile the Tshwane free WiFi network has received is directly attributable to its quality and success,’ Tim Genders, COO of Project Isizwe, the NPO behind the project, writes in an online op-ed.

‘Switch off Cape Town, would anyone notice? Joburg and Ethekwini have never really been switched on,’ he writes. ‘Tshwane took accountability to send their network out to where others feared to tread. They rolled it out to where it was most needed – the lowest-income areas. They cared enough for their citizens to think about their long-term uplift. They funded their network to reach the parts that would never be commercially viable for free WiFi.’

Tshwane’s original model relied on municipal funding, which – according to Genders – has ‘clearly produced the best results’. He notes that the project’s monthly cost was less than ZAR7 per user or ‘5% of the cost of water loss and 28% of the cost of illegal electrical connections’, adding that the funding can be supplemented by advertising, but it will always need to be subsidised. ‘You don’t expect street pole adverts to fund a road. With this model the municipality is in control. It can direct the free WiFi to the places that need it most.’

Another possible funding option is municipal-traded free WiFi, a model that has already been rolled out in New York, under the LinkNYC banner. The scheme reinvents the outdated payphone system – the network of old public telephone booths has been replaced by digital advertising boards, with the city selling those rights under 15-year deals in exchange for free, public WiFi. ‘Interestingly, the New York network is a third of Tshwane’s network measured by active monthly users,’ Genders wrote, pointing out that similar deals in South African cities would need to be well thought out. ‘Otherwise, the lowest-income areas will remain neglected.’

A third option is privately funded free WiFi, where hotspots emerge around coffee shops, shopping malls, taxi ranks and spaza shops in a sporadic, unstructured deployment. ‘The biggest problem with this idea is not that it doesn’t work, but that it half works,’ he says.

‘Free WiFi at low-income area shopping malls or taxi ranks can commercially work. The network will stop there and go no further.’ Genders argues that communities need free WiFi most at their schools, community centres and places of worship. ‘A child should go to a safe environment to do their homework, not a taxi rank.’

In November, the Eutelsat-owned satellite broadband service provider Konnect Africa launched its SmartWiFi hotspot service, aiming to enable sales outlets and community hubs to become connectivity points for their surrounding populations. Through a voucher or mobile payment scheme, users are able to access the internet from a distance of several hundred metres around the hotspot. With off-the-shelf WiFi repeaters, that access can be extended to a few kilometres.

Speaking at the AfricaCom conference in Cape Town last year, Konnect Africa CEO Laurent Grimaldi said: ‘This new WiFi hotspot solution is designed specifically to address the needs of the majority of the African population, which lives in rural areas where there is a need to reduce the digital divide.

‘In leveraging the ubiquity of our satellite network and locally operated hotspots, we will foster more productive uses of digital technology to make everyday tasks easier for individuals and allow businesses in more remote areas to expand their footprint. Let’s just think of weather apps to assist farmers, mobile phones to display bus timetables, or better information on market days that can help small producers enlarge their catchment area.’

Microsoft, meanwhile, has taken a different approach, partnering with ISP Brightwave to bring broadband WiFi access to more than 213 000 students at 609 schools, as well as several healthcare clinics in the Eastern Cape’s King Sabata Dalindyebo Local Municipality. The deployment, co-funded by Microsoft and the Universal Service and Access Agency of South Africa, forms part of Microsoft’s Affordable Access Initiative (AAI) , which invests in internet connectivity, energy access and internet of things projects in unserved and underserved communities.

‘Far too many South Africans lack internet connectivity along with the educational, commercial and economic benefits of cloud-based services,’ Paul Garnett, senior director of the AAI team, said at the project launch. ‘Through partnerships such as these, we will be able to empower entrepreneurs to provide connectivity to many more people and, consequently, enable the creation of critical services for many more South Africans who need it most.’

Brightwave already provides broadband internet access in Soweto, offering WiFi data bundles at a tenth of market prices by leveraging an advertising-driven ‘freemium’ model – proving, in a sense, that in the digital space, street pole adverts can sometimes fund a road.