You’ve seen it in countless films and TV shows. As the courtroom drama reaches its climax, the hero lawyers – invariably a plucky crew of beautiful young defence attorneys – spend a thrilling night working through endless boxes of evidence, sifting through piles of paperwork for the key piece of evidence that will exonerate their client.

‘I cringe whenever I see that,’ says Megan Jackson, legal services innovation manager at South African ‘big four’ law firm Webber Wentzel. ‘I want to shout at the screen, “It’s not like that!”.’ In real life, she says, all those boxes of exculpatory evidence would probably be a simple flash drive or email. ‘What we call “documents” are actually no longer paper documents,’ she says. ‘They’re files that are created on computer systems. We had a matter recently where Webber Wentzel’s maritime team had to collect WeChat messages off devices to track the sinking of a ship.

There was also a recent criminal matter where the prosecutors took location data off the suspect’s Fitbit to prove that he was in the area at the time that the crime was committed. So the type of data that legal firms are collecting is very different to that box of printed documents, where the client would tell us: “These are the things that are relevant for discovery.” We’ve had to change the way we collect data, how we view it and how we categorise it. Now it’s commonplace to use electronic discovery platforms to review legal data in its native, electronic format.’

That modern, digital approach doesn’t only apply to legal firms. Across Africa, businesses and organisations are moving to what Microsoft CEO Bill Gates predicted (back in 2005) would soon be the norm: the paperless office. Digital communication and file storage are – just like Jackson says – commonplace. Lagos-based graduate school the Centre for International Advanced and Professional Studies (CIAPS) has been Africa’s pioneering paperless academic institution for the past half-decade, while in 2017 Ethiopian Airlines announced it had eliminated paper entirely from its day-to-day business operations. Kenya’s 2018 national census was entirely digitalised, the Nigerian National Petroleum Corporation (NNPC) announced last year that it was going paperless, and Ghana has now digitalised the clearance of goods through its newly paperless ports.

South Africa’s Department of Home Affairs also recently moved to paperless applications for birth, marriage and death registrations, in what then Home Affairs Minister Malusi Gigaba described as part of ongoing enhancements of the live-capture system to improve service quality by modernising processes. ‘Documents will now be saved electronically and be easily retrieved on request, as opposed to the old paper-based legacy system,’ he said, neatly summing up a large part of the attraction of digital file-keeping.

In a 2018 blog post, Nashua CEO Mark Taylor writes: ‘Reduced costs. Better security and compliance. Increased productivity. And greater employee satisfaction. These are some of the challenges facing business owners every day, no matter the size of the organisation. ‘One of the surest ways to overcome some of these challenges is the transition into a truly digitised working environment. Paperless business is reality and the rapid reduction of paper usage is well under way as more businesses are evolving from physical document storage to digital document management systems.’

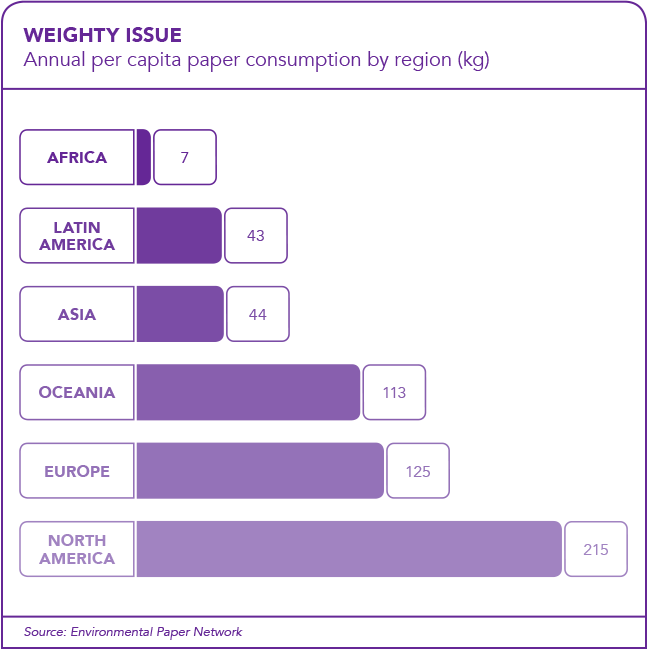

Yet there’s a difference between a digital office and a paperless office – and despite all the cloud technology and data storage options available, many organisations continue to find that paperwork, frustratingly, still involves a lot of, well, paper. Worldwide paper use is steadily increasing year-on-year and, according to data published by the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organisation, it recently exceeded 400 million tons per year. More than half of that consumption occurs in China, the US and Japan, with a further quarter in Europe.

However, the same report found that the entire continent of Africa accounts for just 2% of global paper use; and the Paper Manufact-urers Association of South Africa (Pamsa) estimated in mid-2018 that South Africa’s printing and writing paper consumption had decreased from 1.4 million tons to 1.3 million tons year-on-year. ‘This decline is […] in line with international trends,’ according to Pamsa executive director Jane Molony. ‘The average annual per person consumption in South Africa dropped from around 50 kg in 2011 to close to 40 kg in 2017. Some of this reduction is attributable to cost saving, electronic media substitution and the country’s weak economic growth.’

Kenya, meanwhile, increased its duty on imported paper from 10% to 25% in 2014 on the collective advice of East African Community ministers, prompting several organisations – including Kenya Power and Lighting Company (KPLC) – to send electronic bills to customers. ‘The cost of sending a paper bill through the post office is KSH35, while the cost of sending an electronic bill via SMS is KSH1.53,’ former KPLC CEO Ben Chumo told the Daily Nation. ‘Kenya Power, therefore, saves an estimated KSH43.5 million per month through the electronic bill dispatch, and has so far [this was in early 2017] saved approximately KSH174 million,’ he said.

African governments and businesses are already seeing the benefits of going paperless. A 2018 report, for example, found that the Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA) free trade area would gain US$17.5 billion per year in intra-COMESA exports if its 21 member states were to fully implement digital trade facilitation reforms involving the use of paperless trade facilitation. Perhaps the best example of a cost-saving paperless office comes from South Africa’s Department of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries (DAFF). In 2013, Paul Hardman of the Citrus Growers Association (CGA) started developing PhytClean, an ICT platform that captures, stores and reports, in electronic format, all the data required for official export documentation to trading partners.

Governments use these documents to certify that consignments of agricultural products meet the importing country’s sanitary and phytosanitary rules, and Hardman’s aim was to improve efficiencies, reduce errors and minimise the costs involved in the issuing of those certificates to South African citrus growers. In 2016 PhytClean became a Fruit South Africa (FSA) initiative when the system was adopted by other fruit sectors, and then in March 2018, DAFF asked FSA to extend PhytClean’s functionality and build a full, entirely paperless e-certification platform, ready for roll-out in 2019.

PhytClean now has more than 3 000 registered users up and down the supply chain, in fruit sectors ranging from citrus to apples, pears, peaches and table grapes. ‘Phytclean has proven to be tremendously effective in improving supply chain efficiencies and being able to show that we are compliant at each step, so our growers are very happy to be using it,’ says Hardman. ‘E-certification now takes this to the next level, where DAFF processes can be redesigned to be paperless and become more efficient.’

By eliminating paper from the fruit certification paperwork process – and by improving accuracies, efficiencies and processing times through its digital filing system – Phytclean is expected to see South Africa’s ZAR30 billion agricultural fruit export sector saving as much as ZAR250 million over the next five years. Ultimately, it’s through cost-savings like this that Africa’s move towards paperless offices will continue to show its real value.