Many people across Africa lack access to basic services, cannot get goods delivered easily to their home because they live in an informal dwelling and are vulnerable in emergencies simply because the authorities can’t find their home. Poor addressing means deliveries go astray, businesses cannot be found, aid doesn’t end up where it’s needed and remote areas can be difficult to manage.

This affects nearly 75% of the world’s population, according to UN estimates. Across the continent one of the biggest challenges in providing relief to people living in extreme poverty is locating them.

So what if providing the world with addresses was simplified to just three words? That’s what CEO and co-founder of a system called What3words, Chris Sheldrick, has developed. Speaking at this year’s Design Indaba – held in Cape Town during March – he discussed how using satellite images to divide the world into a grid of 3m by 3m squares could change the way we look at locations. The system’s formula is quite simple. Each block (of which there are 57 trillion in total) is assigned with a unique three-word address, for example toffee.chair.plant.

‘Our goal has been to create an infrastructure that quickly solves a problem many countries have been struggling with for years,’ says Sheldrick. He further states, however, that the system is not meant to replace street addressing, but should rather act as an addition when street addresses are not accurate enough, as well as be an instant, scalable solution where they don’t exist.

The system has become so successful internationally that South African NGO Gateway Health partnered with the company to help ensure pregnant women experiencing difficulty during labour can be located more easily and receive assistance from midwives. Djibouti and Côte d’Ivoire are now part of five countries worldwide that have adopted What3words as an addressing standard for their postal service.

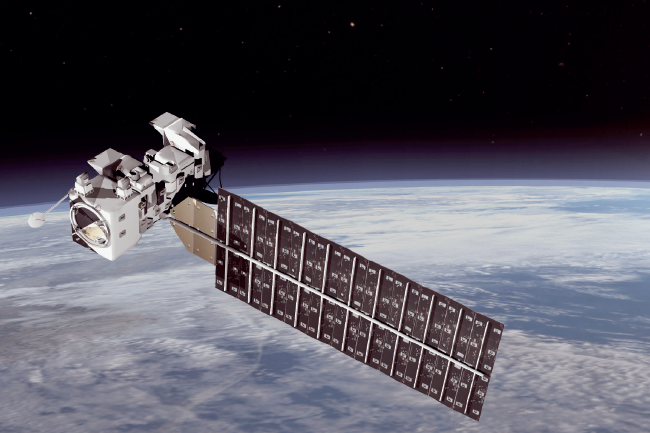

If successfully applied, satellites can do more than just give people an address – it could accelerate a country’s development and transform people’s socio-economic prospects. Last year, a group of Stanford University researchers set about using machine learning – the science of designing computer algorithms that learn from data – to map poverty levels in five African countries (Malawi, Nigeria, Rwanda, Tanzania and Uganda). The researchers used both day- and night-time imagery to identify features that correlate with economic development, says study lead author Neal Jean, who’s also a doctoral student in computer science at Stanford’s School of Engineering. But the team reported that day-time satellite images were about 81% more accurate at predicting poverty in places under the absolute poverty line, and 99% more accurate in areas where incomes are less than half that. ‘Without being told what to look for, our machine-learning algorithm learned to pick out of the imagery many things that are easily recognisable to humans – such as roads, urban areas and farmland.’ These features were then used to predict village-level wealth, as measured in the available survey data.

Another area that can benefit from satellite and high-tech solutions is water management. South Africa is currently recovering from its most severe drought in nearly a century. According to European research media centre Youris.com, local researchers – together with European universities and other organisations – are trying to create the world’s first savannah water use and stress maps using field and Earth observation data obtained from the European Space Agency’s (ESA) Sentinel satellites. These maps will aim to help smallholder farmers better cope with inadequate rainfall and plan irrigation accordingly. Last year, researchers collected their first field data in one of Africa’s best-known patches of savannah – the Kruger National Park – much around the same time the ESA released its African mosaic, including 7 000 cloud-free satellite images captured by the Sentinel-2A.

Satellite technology is also much more accurate when it comes to predicting, monitoring and mitigating disasters such as famine and drought. Take, for example, remote sensing for disaster management.

According to a 2012 report by the UN’s relief agency, Nigeria has one of the worst records of disaster management in sub-Saharan Africa. Since then, the mission control centre situated at the National Environment Management Authority’s headquarters in Nigeria’s capital, Abuja, started using its Cospas-Sarsat system to provide a solution. The system detects distress alerts and location data used in rescue operations. During the disaster-prevention stage, a geographic information system manages the data required for vulnerability and hazard assessment. It ultimately acts as a tool in the disaster preparedness stage for planning evacuation routes, designing centres for emergency operations as well as the integration of satellite data with other relevant data in the design of disaster-warning systems.

This type of satellite system is especially important in South Africa, where ‘there’s a fire season somewhere all the time’, according to Philip Frost, researcher at the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR). Summers are some of the worst times, as fires sweep the Mediterranean landscape on the south-west coast, while the warm and dry winters in the north-east of the country often encourage grass fires that consume the savannah.

To monitor sudden outbreaks of fire, CSIR scientists proposed a solution in 2004 – a satellite-based fire-alert system. ‘The idea from the beginning was to monitor the transmission lines around the country and use cellphone technology such as text messaging to immediately alert people whenever there is a fire, which will then give them the opportunity to do something about it,’ says Frost.

Using moderate resolution imaging spectroradiometer satellite data (which is free and readily available, courtesy of NASA’s Terra and Aqua satellites), the CSIR’s Advanced Fire Information System was developed. It uses an advanced geospatial information processing system that detects fires and alerts infrastructure owners, land managers, disaster management and fire protection personnel of fires in their areas. The wildfire-detection kit worked so well that, in 2013, the technology was implemented in Angola, forming part of an MOU between the CSIR and National Technology Centre of the Angolan Ministry of Science and Technology.

Since Africa started using mapping through satellite, the role it plays in understanding communities’ needs, locating people at risk, improving lives with the help of NGOs and aid organisations has become increasingly evident. And now, with the ability to locate those in remote areas quicker and more easily, this may even prevent or at least slow the spread of infectious diseases in future outbreaks.