In a push to cement fragile rights, Egyptian women have been battling a “shocking” draft bill influenced by Islamic law which would have deepened a system of guardianship further restricting their daily lives.

Nutritionist Mai Nasser remembered how difficult things were already for her mother after her parents divorced when she was a baby.

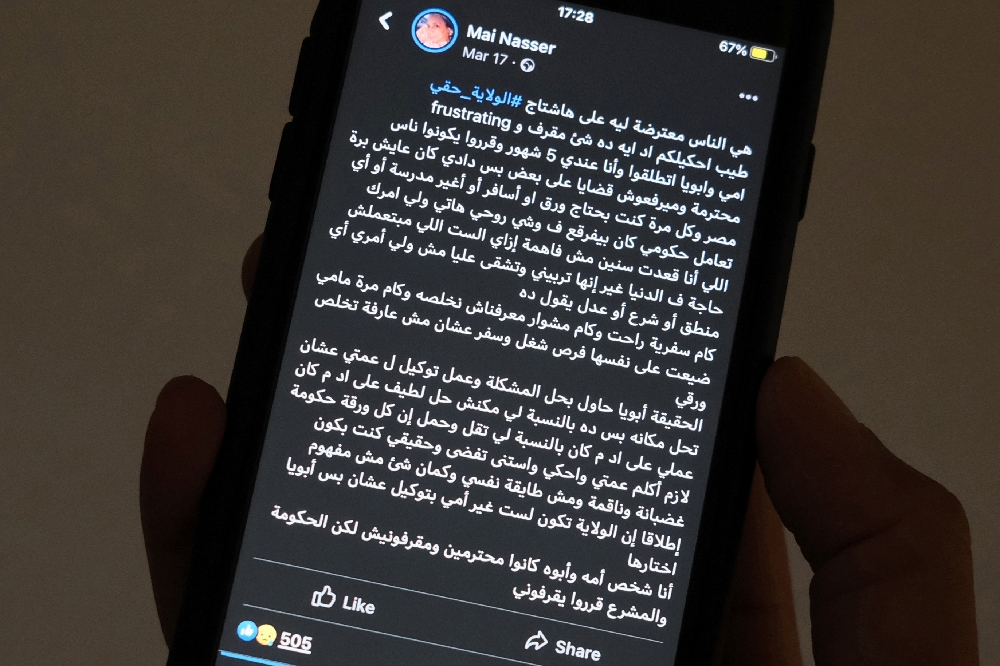

“Every time I needed papers to change schools or to travel or to access any government service, I had to wait for a signature from my father overseas,” Nasser, who is now in her 30s, wrote on social media.

She was using a widely-shared hashtag “#guardianship_is_my_right”, a campaign spearheaded by feminist groups and women seeking to take back power over their lives launched in response to the proposals brought before the Egyptian parliament earlier this year.

Different social background

The draft bill would have “imposed the guardianship of a man – whether he is a father, a husband, or a brother — on a woman,” said Hoda Elsadda, a Cairo University literature professor and chair of the Women and Memory Forum rights group.

“It even granted the father or brother the right to forcibly annul a marriage between a daughter or sister to a man on the grounds of him hailing from a different social background.”

The bill has been shelved for the time being amid the outcry.

But proposed changes to the personal status law had included women being unable to travel abroad without a male guardian’s consent and barring mothers from registering a child’s birth certificate or passport.

‘Shocking’

It would have robbed “women of their legal capacity, and set Egypt back some 200 years,” said Nehad Abo El-Komsan, feminist activist and president of the Egyptian Centre for Women’s Rights, who called the bill “shocking”.

Women’s political rights have improved in recent years – there are currently eight women ministers, or almost a quarter of the cabinet. And women hold some 168 seats in parliament out of 569.

Under constitutional reforms adopted in 2019, women must make up a minimum of 25 percent of MPs in the lower chamber.

But in their daily lives women have no authority over their children or their own personal lives – rights which are delegated to the men in their families.

No rights over children

Elsadda noted that since Egypt’s founding as a modern state in the 19th century, women have been marginalised and their rights relegated.

“In 1956, Egyptian women gained political rights such as voting, running for public office and reaching the highest echelons in the state, but the personal status law remains the same since it was passed in 1920,” she said.

“Women do not have the legal capacity that allows them the right to have guardianship over themselves and their children and puts them under the control of males in the family,” she added.

Earlier this month, the country’s Supreme Judicial Council decided in a meeting headed by President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi to allow women for the first time to work in the public prosecutor’s office and State Council.

But Omnia Taher, a law professor at Al-Azhar University, said the decision was a “cosmetic change”.

There is “a great fear this decision will appoint a group of female judges as a one-off only. Gender discrimination won’t be eliminated,” she said.

Taher launched an initiative called “She has a right to the bar” after she was refused an appointment in 2013 as a judge to the State Council.

Elsadda also remains sceptical of the recent changes, highlighting how women are constantly confronted by bureaucratic barriers.

“The minister who represents the state in international summits does not have legal guardianship over her children,” she said, and for example cannot collect vital papers such as leaving certificates from schools “without the presence of the father”.

Women also cannot control their children’s bank accounts, as the fathers are the children’s legal guardians.

“The bank manager who deals with funds … worth millions can’t deposit money for her children in their savings accounts … from her own money,” Elsadda added.

Top imam weighs in

In May the grand imam of the Cairo-based Al-Azhar, the top theological institution representing Sunni Muslims worldwide, weighed in on the debate.

Sheikh Ahmed al-Tayeb said on Twitter that there is no religious edict preventing women from holding high-ranking positions, travelling alone or having an appropriate share of inheritance rights.

And he added that “their guardians could not ban them from marrying without a valid reason”.

But he stopped short of saying women should have equal rights to men.

And some believe the only way to protect women’s rights is to enshrine them in civil law.

The personal status law “must be civil, otherwise we will remain in a crisis of religious interpretation all the time,” said journalist Raneem Al-Afifi, who has launched a campaign to boost gender coverage in the media.

She fears the draft law has only been shelved as “a temporary measure to assuage women’s anger”.

“The contradiction remains between the rights they (women) have in the public sphere and the absence of rights in the private sphere,” agreed Elsadda.

Source: AFP

Picture: AFP