Start right at the beginning, says Wayne Poggenpoel, competency lead of risk advisory services at SkX, a financial consulting firm based in Johannesburg. Begin with the why, the who, and the three how-tos. Why does your organisation want to manage risk? Who will manage these risks? How will you manage these risks? How will you communicate relevant information? And how – and by whom – will assurance be provided on these risks?

When outlining the plan for a company’s risk-management strategy, the principles of project management 101 apply, and it’s crucial to tick these boxes one by one. ‘Effective risk management requires that the foundation, its components and the measures or arrangements within which risk management is undertaken, are embedded within the company and followed by the entire staff complement,’ says Poggenpoel. Any company looking to create a risk-management plan must understand clearly the environment in which it operates and its specific objectives. Then it must carefully outline the plan, which should reflect the people, processes, systems, accountabilities, limits and resources needed to achieve optimal risk management.

According to Poggenpoel, the structure of the plan should include a policy outlining the company’s approach to managing risk; a description of the responsibilities involved in managing risk; as well as a set of guidelines on how to manage risk across the organisation. Those guidelines should use a common risk language to ensure that everyone understands them. In addition, they should outline risk thresholds to illustrate what is acceptable and what is not. Further, the guidelines must include a process that identifies, assesses and treats risk. They should also feature a set of risk criteria as well as assurance underpinning the process.

The risk-management plan must be integrated with supporting IT systems, and it should outline communication procedures (how and with whom information about risk will be shared). It must identify expected outputs, including for reporting purposes, as well as the resources required to implement the plan in terms of people, capital, technology and relationships. ‘Risk managers are in a unique position to connect the proverbial dots; […to find] the linkages and trends in information – vertically and horizontally, from a number of different planes – that enable you to navigate the level and pace of complexity for what we are going through in the world and, certainly, South Africa,’ says South African Minister of Public Enterprises Pravin Gordhan in the Institute of Risk Management of South Africa (IRMSA) Risk Report 2019.

In the report, risk experts were asked to give a brief summary of their main concerns. Mervyn King of the King Committee names a lack of leadership in South Africa; Tankiso Moloi, professor of accounting at the University of Johannesburg, cites limited state resources to address societal issues; for Bridy Paxton of Marsh it is a lack of accountability from the state; Gabrielle Reid from S-RM Intelligence and Risk Consulting highlights the consequences of political mismanagement; and Parmi Natesan of the Institute of Directors in Southern Africa says that not taking broader stakeholder interests into consideration when setting strategy and making decisions was a major concern.

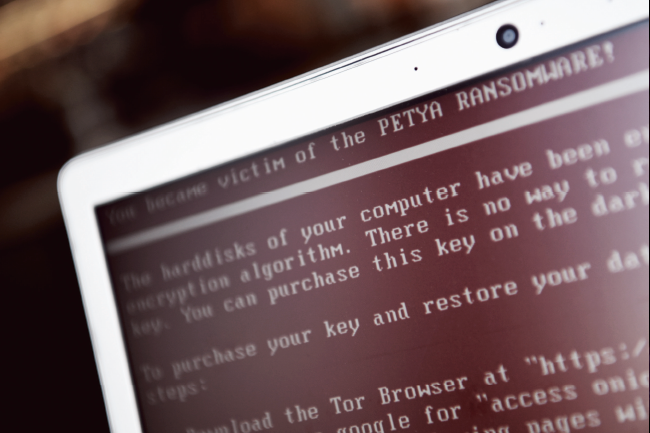

Risk managers have to contend with obvious risks such as cybercrime while keeping an eye on macro- and micro-economic issues, including political risks on home soil and abroad – and often the two overlap. The key, according to Gordhan, ‘is to connect the dots between these phenomena and to ask the question: where to from here and how do we as public officials or private operators in companies influence and chart our own destiny’. Poggenpoel says that typical risks to businesses in South Africa include cyberattacks, energy-price shocks, political uncertainty, fraud and corruption, labour unrest and strike action, and inadequate education and skills development of the labour market. IRMSA echoes these, listing the top three risks to the industry in South Africa as a failure of governance, a lack of skills development and cyberattacks. Micro- and macro-economic developments sit at numbers five and six on the list respectively. While the categories tend to differ from one industry to the next, risk can generally be grouped into strategic, compliance, operational, financial and reputational, according to Poggenpoel.

It’s in responding to these risks that companies have options. They can choose to either accept or tolerate a risk, in which they acknowledge the level of risk inherent in an event and continue to pursue company objectives. ‘This may occur if or when the management team believes that the costs of responding to the risk do not create or protect sufficient value to justify the additional effort,’ says Poggenpoel. In deciding to avoid the risk, a company may opt not to pursue or continue the activity that gives rise to the risk exposure, which will negate the risk but also the opportunity to benefit from the activity. It’s in managing the risk where one can possibly influence the likelihood of an event, he says. ‘This option usually adjusts either the operating processes or human behaviour that give rise to a particular risk,’ he adds. Two simple examples include introducing mandatory rest breaks for long-distance drivers, thereby reducing the likelihood of accidents; and increasing the acceptance criteria for issuing short-term debt, thereby improving the quality of debtor and, hence, decreasing the likelihood of default.

Another option is to transfer the risk at a price to other parties. This usually focuses on the financial consequences of a risk (such as loss of income), unexpected expenditure or loss, and includes contractual agreements, outsourcing, risk financing, and insurance. ‘Risk transfer is a risk-management technique whereby the risk of loss is transferred to another party through a contract – for instance, a hold harmless clause – or to an insurance company, normally at a fee or premium,’ says Poggenpoel. ‘Risks that are transferred normally refer to activities with a low probability of occurring but with a large financial impact.’ He says the best response is to transfer a portion or all of the risk to a third party by purchasing insurance, hedging, outsourcing or entering into partnerships.

Companies can also choose to exploit the opportunity, adds Poggenpoel. For positive risks, the company may allocate additional resources to exploit and benefit from the uncertainty, which is often the case when external trends or factors move in the company’s favour, such as movements in the exchange rate, relaxation of legislation or actions of competitors.

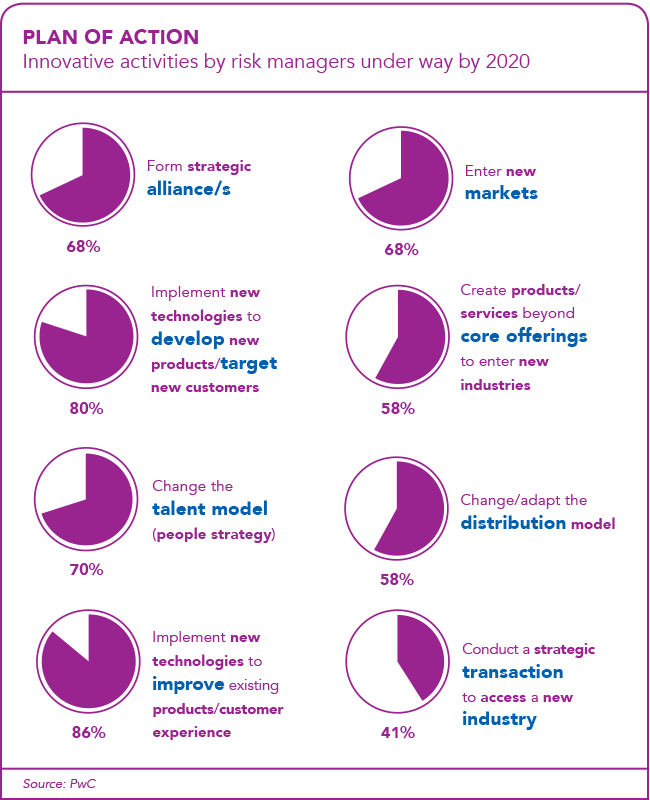

PwC, in its 2018 Risk in Review report, found that 15% of the 1 500 respondents (all senior risk executives) considered their risk-management programmes to be very effective in managing innovation-related risks. Another 45% considered their programmes to be ‘somewhat’ effective. The report collectively names these two groups the ‘adapters’, with their defining being adaptability.

Adapters have already changed how they tackle innovation risk but their practices differ in four key ways, namely the high level of their involvement throughout the innovation cycle; their use of multiple strategies to manage their exposure to innovation-related risk (such as sharing risk and adjusting the risk appetite); the new skills, technologies and capabilities they continuously add as they lean into innovation; and the broad set of mechanisms and metrics they use to monitor and measure the efficacy of their risk-management programmes and adjust for vulnerabilities, as needed. ‘[As] the saying goes: “With chaos comes opportunities”,’ says Poggenpoel, and the riskier the environment, the greater the opportunity for risk experts to make a difference and provide the necessary risk-management value to companies, especially in what he refers to as a current sea of uncertainty and volatility. As the PwC report puts it, ‘the present is marked by such change and innovation that it is described in revolutionary terms: the Fourth Industrial Revolution, the second machine age, the cognitive age. And history teaches us that when innovation rises, so do risks’.

PwC explains that a good risk manager is more likely, before the planning phase, to advise on innovative activities, and to call a halt to activities, based on risk assessments and risk-based alternatives. ‘These findings fortify findings by other studies showing that organisations manage risk more effectively if senior risk executives are involved in high-level strategising with business leaders and the board about new investments, and are more attuned to risks in internal and external operations. Without such deep involvement, risk executives are more likely to resist otherwise promising innovations or be blindsided by critical risks,’ the report states.

According to Poggenpoel, ‘the better we as risk experts are able to use the risk information for better future predictive purposes, the better it is for us to enable management to make more informed decisions’. Risk management is challenging enough for any business but for companies with global operations and interests, it can even be more demanding. ‘The risk landscape is always evolving, and organisations must always be able to respond effectively and efficiently,’ he says. It’s for this reason that companies look to external risk consultants – ‘to stay agile’.

As quoted in the PwC report, Kimberly Johnson, COO of Fannie Mae, says: ‘Innovation risk is a strategic question. The risk of not innovating is just as high as the risk of innovating, if not higher.’ Times like these certainly call for innovative solutions.