In 1981, a group of what must have been very adventurous yet apprehensive travel agents for the first time booked travel packages with Thomson Holidays by punching requests into their TVs, using so-called Viewdata technology. Three years later Jane Snowball, the first-ever online shopper, bought her groceries online at a Tesco supermarket in the UK. This has long been considered the dawn of online retail.

That was nearly four decades ago and online has since very deliberately dismantled the empire of brick-and-mortar retail. In some instances the shift has been through sheer annexation, what Amazon has done to chain bookstores. And in others conventional physical stores have done the dismantling themselves by migrating, at least in part, to online commerce.

However, with online retail accounting for 1.4% of total retail spending in South Africa, according to IOL Business Report, almost all South Africans do their shopping by physically taking product off the shelf. Don’t write off the local retailer around the corner just yet, not in Africa, anyway. This can either be attributed to preference or inadequate access to the financial infrastructure on which online retail relies – credit cards, computers, smartphones, the internet and so on. Cash continues to reign supreme in South Africa.

‘This lags substantially behind other countries in which the role of e-commerce has risen extensively, accounting for up to 20% in the most sophisticated markets,’ according to Online Retailing in South Africa: an Overview (a paper prepared for the Centre for Competition, Regulation and Economic Development).

Moreover, the latest e-Commerce Industry Report (2017) shows that e-commerce buyers in South Africa are predominantly higher-income earners with full-time employment, 35% of this grouping earning above ZAR30 000 per month, as noted in the same paper. It would be remiss not to make mention here of South Africa’s dismal unemployment record, which is conservatively estimated at 29%, according to the latest numbers from Statistics South Africa.

Justifiably then, the e-commerce sector in South Africa has for many years been thought of as being in its infancy, begging the question: when will the industry eventually advance to toddler status? And if the sector in South Africa continues in this state, what would that make of e-commerce in the rest of Africa?

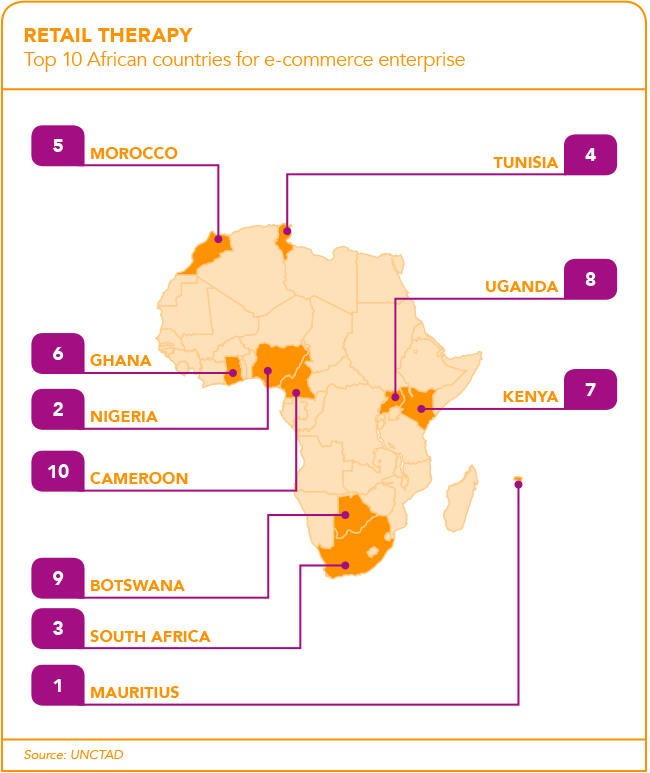

Embryonic? Not quite. The potential across the continent’s key regions is arguably more enticing to e-commerce business than in South Africa, with Mauritius and Nigeria ranking higher than the former in the UN Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) B2C e-commerce index 2018. But this massive potential throughout Africa is interwoven with logistical obstacles. ‘In Africa, there’s no address system in most of the cities,’ Jumia co-founder and co-CEO Sacha Poignonnec said in a January 2019 video interview with McKinsey (where he was employed prior to co-founding Jumia, Africa’s largest e-commerce retailer). ‘For someone to find a consumer, you need to have a local partner who knows where the consumer is, based on very subjective information. And, for example, if you say in a city in Africa, “I live in the third street by the church with the blue door”, that’s the address.’

Speaking at the 2018 AfricaCom conference, former board member of MTN and Jumia, Herman Singh, also highlighted the continent’s potential client base of 400 million internet users, but mentioned the rapidly emerging middle-class expected to grow by 54% between 2020 and 2030, and decreasing data costs across many regions. A perfect climate for e-commerce germination.

African e-commerce company Jumia has a client base of 4.8 million and, in April 2019, it listed on the New York Stock Exchange with an IPO valuation of US$1.12 billion. The company has recently struggled with internal fraud and external legal threats, and earlier obstacles included payment and delivery issues.

Due to some investor jitters, the Jumia share price has dropped from its initial listing price but despite the controversy, the company notes in its 2019 Q2 investor report a 69% year-on-year increase in its gross merchandise volume (GMV), as well as year-on-year increases of 90% in marketplace revenue, and 94% in gross profit.

‘From the outside, you look at Africa, you read the news, and you think it’s going to be very difficult – everything is going to be very difficult,’ says Poignonnec. (He adds that the company sold only 10 mobile phones on its first day of business.) ‘One of the barriers, obviously, of e-commerce is the logistics, because we have to move the products from the merchants who are selling the products to the consumer who is ordering the product. And logistics is obviously a big challenge for whoever knows Africa.’

One of South Africa’s leading e-commerce retailers, Takealot Online (which includes the Takealot.com, Superbalist.com and Mr D Food businesses), reported GMV of 53% and a group gross margin improvement of 2% after delivery costs. ‘The growth in our businesses is the result of executing well; providing good customer service and value and convenience to consumers,’ says Takealot founder and CEO Kim Reid in Naspers’ 2019 integrated annual report. ‘But we’ve also got the wind behind us, with great room for more e-commerce growth in South Africa.’

An intriguing question then: how does one online retailer distinguish itself from the next with the obvious absence of aesthetics and other differentiating tools available to physical stores? Simple. Product and price. In a store you can pick something up, try it on and make the final choice of whatever you want to purchase based on your criteria, explains Jessica Carolissen, brand manager of OneDayOnly, a South African online flash-sale retailer. Online retail, however, requires clever content curation, imagery and product descriptions to sell what is essentially an image on the screen.

‘With more and more players coming into the market, along with a tricky financial climate, consumers have become more agnostic in their support [of one retailer or the next],’ she says. ‘When price and product are the same, the expected factors come into play, including a good discount and great customer journey experience.

‘From the minute you land on the website until you have checked out your cart, excellent customer service that feels personal [is essential] – good old brand love,’ according to Carolissen. ‘We’ve seen a massive influx of new e-commerce competitors emerge in the last few years with more people turning to online shopping for its convenience,’ she says. Initial concerns about the safety of online shopping have also subsided. And as in all retail sectors, 3D and digital, there is buzz around the ‘tech-savvy youth market’, which will soon be of age and in possession of a debit or credit account, if not already, depending on which generation is referred to.

Mobile penetration has had a profound impact on retail in South Africa and the rest of Africa. ‘Many e-commerce businesses that want to succeed in Africa take the mobile-first approach to ensure they meet the users where they are,’ says Carolissen. Cash-on-delivery and other innovative approaches by retailers such as Jumia is a good example of this, even if it does lead to various other complexities in the system, which has caused its fair share of misery for the aforementioned retailer.

Carolissen argues that companies such as Jumia ‘and their out-of-the-box thinking and solutions to Africa’s operational problems’, lends the African retail model more to China’s way of doing business than that of the US and other developed Western countries. ‘Africa’s focus has been less on chasing cheap capital and more on growing revenue and profit with the marketplace, or buying for customers on their behalf,’ she says. ‘These approaches have made the Chinese online market a very successful example to follow.’

In its latest integrated report, Naspers, the majority stakeholder in Takealot, explains that a key advantage for Takealot is its own established end-to-end delivery system, which enables the company to push technology into the business and provide a better customer experience. This, according to the company, enables same-day delivery, weekend deliveries, pick-up points and more predictable delivery cycles. Takealot now delivers up to 1.3 million parcels a month, and in future the company will focus on improving logistics and certainty of delivery.

The main drivers for e-commerce across Africa is twofold, says Carolissen. There are the obvious benefits to doing business online, such as the opportunity and scope that online affords. ‘Starting a business and selling a product has been made easier,’ she says. ‘It is cost-effective for a small to medium-sized business to sell products online.’ The widespread adoption of smartphones, along with a call for convenience, has also led enabled consumers to consider online shopping.

For the future of e-commerce in South Africa, Carolissen sees a continuation of higher adoption rates and a wider array of payment options. Also, more brick-and-mortar stores will go digital, while people will increasingly trust online platforms. However, she warns, we must be aware of the misper-ception that online shopping is business as usual for Africans. ‘Because we are immersed in e-commerce every day, it may feel as though everyone is shopping online, which is not the case. We are dealing with a small subset of active online users,’ she says.

‘There is definitely more work to be done, and that is why while it is daunting when new players come onto the e-commerce scene, we are also excited that there are more brands educating consumers that it is safe and convenient to shop online.’