In their 2017 Infrastructure Report Card, the South African Institute of Civil Engineering scored South Africa’s public infrastructure a D+, one notch above D, which the institute views as posing a risk of failure; not coping with demand; and being poorly maintained. Alongside the challenges, there are many opportunities for institutions to play what the Development Bank of Southern Africa (DBSA) says is a ‘catalytic’ role in furthering development in South Africa and the rest of the continent.

‘There are huge challenges,’ says Chucheka Mhlongo, head of infrastructure finance at the DBSA. ‘The biggest challenge is unstructured development taking place, which has huge negative implications for the country,’ he says. ‘The first thing we need to get right is to ensure that planning is in place and the preparation of infrastructure is correct.’

The bank’s mandate is mainly around infrastructure development, which includes projects in energy, telecoms, transport links (roads, rails and ports), ICT and waterworks, among others, but banks such as the DBSA and the AfDB are no longer just pure credit lenders. The DBSA’s in-house divisions, including its infrastructure delivery division, offer programme and project implementation capabilities, along with providing traditional services, including capital provision.

Take, for example, the ZAR200 billion renewable energy infrastructure project in South Africa, in which the vast majority of funding came from the private sector, with the DBSA supplying the rest. ‘We recognise the skills shortages in municipal departments, especially in the technical and financial areas, which impacts the ability of other areas within municipalities to plan projects at scale and finalise these on time,’ says Mhlongo. When a project has been identified, the immediate consideration is to check if it has been prepared properly to gauge the accuracy of the cost estimate. That also reveals if the capital amount to be raised will cover project costs.

He notes that if it transpires that the project has not been fully designed, it becomes the bank’s first priority to support the municipality. ‘We also use our development contribution to partly grant the development of the project. The next step will be to check the strategic feat of the project, to check its alignment with the NDP and its local, regional and national priorities,’ he says.

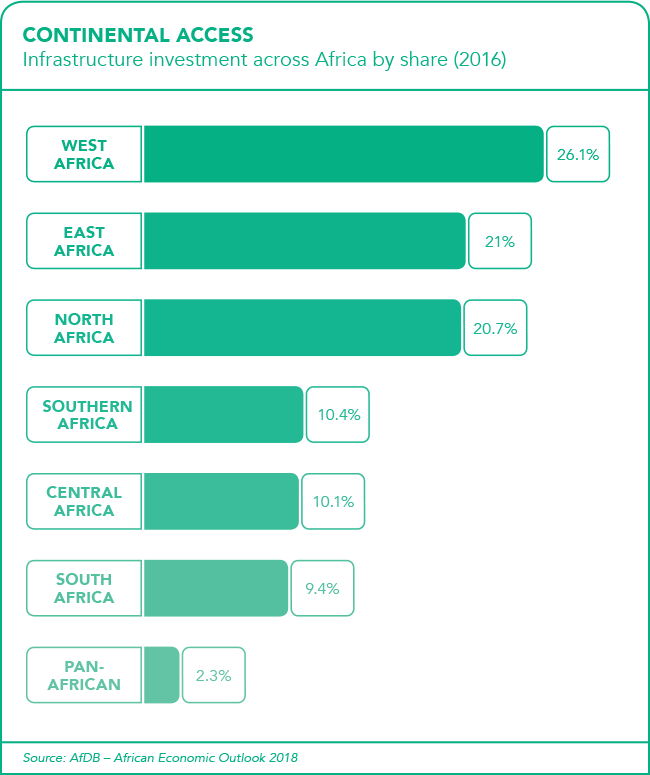

Two-thirds of DBSA projects are in South Africa and the remainder are outside of its borders. The DBSA invested ZAR12.4 billion in infrastructure finance in the 2017 financial year, while also helping to attract another ZAR31.9 billion in investment from third-party investors. Moreover, in December 2018 the Islamic Development Bank (IDB) approved US$281.55 million for development in its 57 member states, including US$134.5 million for a natural gas transmission project in Tunisia, US$19.2 million for new rural roads in Senegal, and US$26 million towards the healthcare system in Djibouti. The AfDB operates in 13 Southern African member countries with an ongoing portfolio of US$11 billion – 42% of its portfolio resides in South Africa, 11% in Namibia, 9% in Zambia and 7% in Angola.

A group of development banks released a report in 2015 titled From Billions to Trillions: Transforming Development Finance, in which they stressed the importance of a paradigm shift in the role and use of development finance to achieve the global Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The DBSA’s strategy of acting as a catalyst for infrastructure investment relies heavily on this report. The bank is able to leverage its strategic partnerships with development finance institutions around the world, including the World Bank Group, the AfDB, French Development Agency and German Development Bank. The DBSA is involved in various transboundary projects in Africa, such as the North-South corridor, the Southern Africa Power Pool and the Lapsset corridor in Kenya.

The Association of African Development Finance Institutions (AADFI) was established in 1975 and is headquartered in Côte d’Ivoire’s capital, Abidjan. The international organisation was created under the auspices of the AfDB and membership is open to any banking or finance institution in Africa. Being a member enables banking and finance institutions to benefit from AADFI assistance for lines of credit from development partners. Through its wide network of banking and financial institutions, the association enters into dialogue with concerning parties on development policies and issues of project financing and promotion in Africa. Moreover, the institution offers technical assistance for in-house training, along with staff exchange and secondments to member institutions.

In the same vein, the AfDB, with the Islamic Corporation for the Insurance of Investment and Export Credit, African Trade Insurance Agency and GuarantCo, entered into an MoU for a Co-Guarantee Platform (CGP) in November 2018. The partners created the CGP to address the high risk and lack of risk-mitigation tools associated with traditional lenders across the African continent. ‘The platform is intended to increase the volume of insurance and guarantee solutions available to project sponsors and their bankers in a market-responsible manner,’ according to the AfDB. The aim is to mobilise greater amounts of investment in the region in the absence of affordable risk mitigation products. The platform is open to participants, including official development institutions and players, in the private sector.

‘There are many guarantee providers that can offer various types of credit enhancement and risk mitigation instruments in Africa, but co-operation among them has been either non-existent or on an ad hoc basis. Hence the need for a more formal collaboration among guarantee providers to maximise the use of their products in Africa,’ said Akinwumi Adesina, president of the AfDB Group.

Speaking at the AfDB’s Opportunity Seminar in Pretoria, South Africa, Lerato Motsamai, the founder and MD of Petrolink, noted that ‘there are a vast amount of opportunities that I was not aware of’, and asked for another session to enlighten SMEs on how they could become part of procurement opportunities, and how they could leverage the bank’s resources.

For all its challenges, and maybe because of them, Africa is ground zero for actions of economic empowerment through development. In the Billions to Trillions report, the group of lenders acknowledged their shared commitment to reducing poverty and inequality worldwide. ‘The MDBs [multilateral development banks] and the IMF reaffirm their commitment to ramping up efforts to further enhance co-ordination and complementarity among themselves, as well as with other development actors, in the implementation of the proposed SDGs in each of the developing countries they serve,’ the report states.

In November 2018, IDB president Bandar Hajjar laid out the challenges facing most of its member states. ‘Our 57 member countries, as part of the developing world, are facing disproportionate, complex, economic and social challenges due to their diverse economies,’ he said, before detailing each of them: government red tape, structural flaws in the socio-economic fabric, nepotism and bribery, ecological issues… And so it continues. ‘The current development model of most member countries, which depends on public spending as the engine of economic growth, and depends on exporting raw material that does not create added value, becomes unable to create new jobs to accommodate the newcomers to the job market annually,’ he said.

Hajjar and the team at IDB’s five-year plan for the economic development of member states focuses on the root causes of development challenges rather than their symptoms. The new model is centred on being a catalyst for development, essentially transforming the bank from an on-balance sheet funding provider to a development enabler, market creator and investment facilitator, according to Hajjar. ‘It prepares people for the future economy, focusing on partnership, especially with private sector, STI [science,technology and innovation], global value chain, and making education more relevant to the economy.

‘We need to have a paradigm shift in the development community to be able to keep its promise of achieving the SDGs and leave no one behind,’ he said. ‘The development and donors’ community should understand that financing is not an end in itself; it is just a means to empower people to take the lead in improving their lives.’