In Angola last year, China opened a US$11 billion credit facility following an agreement signed by Angola’s President João Lourenço during an official visit to China. The facility intends to finance 78 Angolan development projects, mostly relating to infrastructure.

In Kenya, meanwhile, the state-owned Aviation Industry Corporation of China unveiled its US$400 million Global Trade Centre in Nairobi, which is hailed as China’s largest real estate investment in Africa to date. On completion in 2020, it will be one of East Africa’s tallest landmarks, scraping the sky at 184m and featuring office towers, residential and commercial units as well as a five-star hotel. In South Africa, the continent’s largest sourcing fairs – China Homelife and China Machinex 2018 – attracted more than 600 Chinese firms seeking South African and African business partners. The exhibitions further the objectives of the Forum on China-Africa Co-operation (FOCAC) to increase Chinese-African trade. These are just three examples of China’s influence in Africa, and which all took place in September 2018.

Also during that month, Chinese President Xi Jinping pledged US$60 billion in aid and loans for Africa at the FOCAC summit in Beijing. Africa’s top leaders attended the high-level gathering, with only five heads of state (DRC, Tanzania, Burundi, Eritrea, Algeria) represented by their prime minister or another substitute, according to Africanews.com. The Gambia, São Tomé and Principe, and Burkina Faso joined FOCAC this year for the first time after cutting ties with Taiwan.

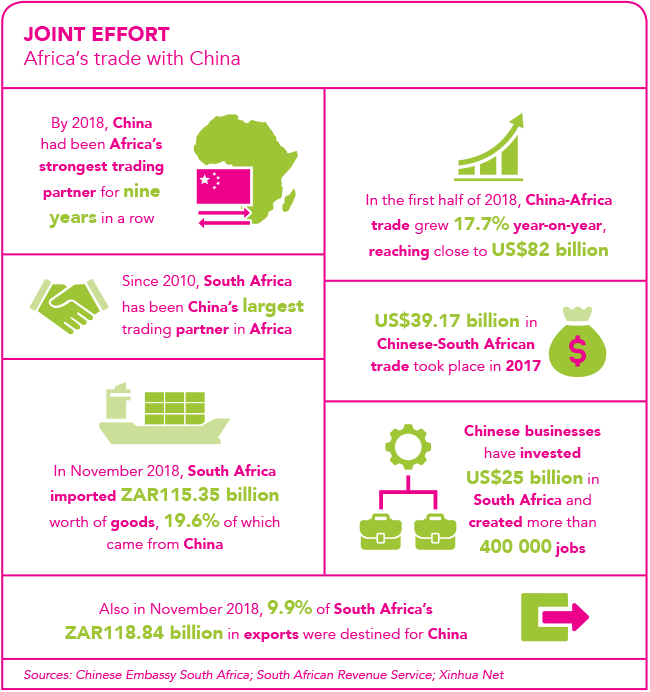

China has transformed itself from a relatively small investor in Africa to the continent’s largest economic partner, states McKinsey in a report titled Dance of the Lions and Dragons. The 2017 publication puts bilateral trade at a growth rate of about 20% annually and foreign direct investment (FDI) at about 40% per annum over the past decade. Furthermore, it says there are more than 10 000 Chinese-owned firms operating in Africa today, whose revenue could well reach US$440 billion by 2025.

However, these figures have been questioned by academics asking for better definitions of what makes an enterprise ‘Chinese-owned’. For instance, it should exclude the large numbers of Chinese migrants investing money they have earned in Africa, because this involves an intra-African flow of funds rather than from China into Africa.

Yet it’s undisputed that, for the past decade, China has been South Africa’s largest trading partner. Xinhua reports that bilateral trade amounted to US$39 billion in 2017. The Chinese state news agency emphasises the goodwill between the two nations, reporting from the FOCAC summit. ‘South African President Cyril Ramaphosa dismissed allegations of China practising colonialism in Africa, saying China instead has been a partner in boosting social and economic development on the continent.’

China-Africa relations are characterised by China’s non-interference in the domestic politics of African states and in providing aid and infrastructure finance that seemingly have ‘no strings attached’. In contrast, Western partners often make their aid, trade and investment in Africa conditional on democracy and human rights compliance. China’s relations with Africa also differ from those of fellow BRICS member India.

Although the two Asian nations in the grouping are largely motivated by access to energy resources and are heavily invested in Africa’s commodities, China’s trade is primarily state-orchestrated whereas India’s is driven by the private sector, says Abdullah Verachia, CEO of consultancy firm the Strategists.

There has been criticism from some quarters regarding African countries with high Chinese debt exposure. According to a recent BBC Reality Check article, researchers from John Hopkins University in the US have identified 17 African countries with large Chinese loans. For example, around 77% of Djibouti’s debt is reportedly Chinese, while Congo is estimated to owe about US$7 billion to China. Zambia’s debt in 2017 was US$8.7 billion, the majority (US$6.4 billion) from Chinese lenders. However, according to a report by the Voice of America, Chinese loans only make up a small amount of Africa’s debt burden.

Quoting W Gyude Moore, a visiting fellow at the Centre for Global Development, the report said the continent’s total debt burden was about US$6 trillion, with the majority lent by organisations such as the IMF, World Bank and Western countries. Some African loans are part of China’s Belt and Road Initiative, a modern ‘Silk Road’ consisting of overland corridors and a maritime route of shipping lanes that will directly connect China with the rest of the world. ‘From South-East Asia to Eastern Europe and Africa, Belt and Road includes 71 countries that account for half the world’s population and a quarter of global GDP,’ according to the Guardian. The initiative is reportedly going to cost more than US$1 trillion.

Chinese money is visible all across the African continent: in the gleaming AU headquarters in Addis Ababa, and in the upgraded airports in Kenya, Mauritius, Mozambique, Nigeria and Zimbabwe; in special economic zones as well as in the growing number of new ports, roads and railways. There is, for example, the Addis Ababa-Djibouti Railway, the continent’s first trans-boundary and longest electrified railway line, and the Madaraka Express from Mombasa to Nairobi, which has halved the cost of transporting containers on this route. The line is set for further expansion to interconnect Kenya with Uganda, Tanzania, Rwanda, Burundi, South Sudan and Ethiopia.

In addition to modernising Africa’s dilapidated infrastructure and constructing imposing new buildings, Chinese loans have also paid for power generation. While Chinese companies often import Chinese labourers, surveys have found the vast majority of newly created jobs going to local workforces. Deryn Graham, PR manager at Proudly SA, gives the example of privately owned Chinese firm Hisense, a consumer white goods and electronics company, which launched in South Africa 21 years ago and is a member of Proudly SA.

‘Hisense set up its base at Atlantis, in the Western Cape, where unemployment and crime are major challenges facing the community,’ he writes in an opinion piece in Business Report. ‘In 2013 they opened a new facility, covering 100 000 m2 and producing 1 200 fridges and 1 700 televisions a day. Their workforce is 98% drawn from Atlantis. This is a great example of a multinational putting down firm roots in a host country, providing jobs and producing goods for local consumption, keeping profits in the country and reinvesting in their own growth and bringing socio-economic improvements to their immediate area.’

According to the Trade and Law Centre (Tralac), 58 Chinese companies invested in South Africa between January 2003 and January 2018, with a capital expenditure of ZAR69.4 billion – mainly in the automotive, electronics, metals and financial services, as well as in the building and construction sectors.

‘South Africa mostly exports raw materials, while it imports manufactured and high-value goods such as machinery and equipment. The balance of trade also continues to be characterised by a substantial trade deficit for South Africa when metals and minerals trade is excluded,’ Kobus van der Wath, founder and CEO of the Beijing Axis, writes in Fin24. He urges South African businesses of all sizes and from all industries to gain a foothold in the Chinese market, to fully yield the benefits.

‘While the increased presence of Chinese construction firms – with their superior construction capabilities – implies competition for SA firms, it also presents an opportunity for them to offer their deep understanding of the African market, provide insight into cultural nuances, and assist with compliance to regulations,’ he says. Key focus areas include raising awareness of one another’s markets and achieving a more strategic understanding of the countries’ respective journeys and working together to leverage Africa’s growth via South Africa-China corporate partnerships. Van der Wath suggests using universities, think tanks and other research platforms to prepare a ‘China-literate’ business community in South Africa and vice versa.

‘China literacy is about awareness, understanding, strategic insight and the ability to engage meaningfully in order to benefit,’ he says. From Africa’s side there needs to be ‘deep insight, strategic planning, policy synchronisation and co-ordination – within Africa and with China – as well as meaningful engagement to ensure good governance, mutually beneficial outcomes and growth’.

In this complex and often misunderstood interaction, African nations must look beyond short-term gains and ensure that China’s relationship provides sustainable benefits for the continent’s future, moving the narrative away from ‘neo-colonialism’ and towards mutual growth through increased globalisation.