In explaining the vastly different pension environments across Africa, Johan Gouws, the head of institutional consulting at Sasfin Wealth, says that ‘offshore investment limits are as high as 70% in Botswana, whereas in Mozambique offshore and equity investment opportunities are limited to non-existent, which has a material impact on the ability to develop effective investment strategies. In many countries inflation [is] at double-figure levels, which makes achieving real returns an even greater challenge’.

Regulatory landscapes, investment opportunities, the ability of governments to affect this potential, and the depth and liquidity of investment markets, all have an impact on the ability to develop effective investment strategies. But generally, investment markets in South Africa are more developed than in the rest of Africa. The retirement fund value chain – including administration, employee-benefit consulting, investment guidance and risk-benefit advice – is not as developed in the rest of the continent, explains Gouws. Skill levels of trustees also vary from country to country, with much education required on fiduciary responsibilities as well as economic and investment principles. ‘Other African countries do not have a similarly well-developed retirement system to the one in South Africa and many people don’t have access to retirement funds unless they are employed in the public sector or very large corporates,’ says Andrew Davison, head of advice at Old Mutual Corporate.

Anne Cabot-Alletzhauser, who heads the Alexander Forbes Research Institute, says that in reality people are willing savers, as the institute’s data suggests, but saving towards retirement is the problem. In an analysis of compulsory savings systems globally Alexander Forbes researchers identified three important insights.

For one, making long-term savings compulsory is problematic for people living on the financial edge if a portion of their savings isn’t applied to a low-cost emergency savings vehicle. ‘Employers could facilitate such a solution. It would still provide adequate retirement savings without requiring that employees sacrifice more of their take-home pay if the retirement savings component is auto-escalated,’ she says. Two, when members are given a choice of how to apply their compulsory savings, it provides the added value of increasing financial literacy and fiscal responsibility. ‘In the Singapore model, once a minimum retirement saving sum is addressed, tax-free savings can be applied to housing, education, health, risk and investing for the benefit of the individual or a multi-generational family.’

Finally, if the financial services industry and governments want these long-term savings to last, there needs to be a focus on helping income earners manage their entire financial journey – not just their retirement. ‘Historically, the industry has only offered financial planning advice to high net-worth individuals. Technological advances mean that compulsory savings can now be refashioned into a guided financial planning framework for all members, including their extended families or lenses of responsibility,’ says Cabot-Alletzhauser. ‘That will be the dramatic shift that Africa, its employers and governments will need to take to secure its future.’

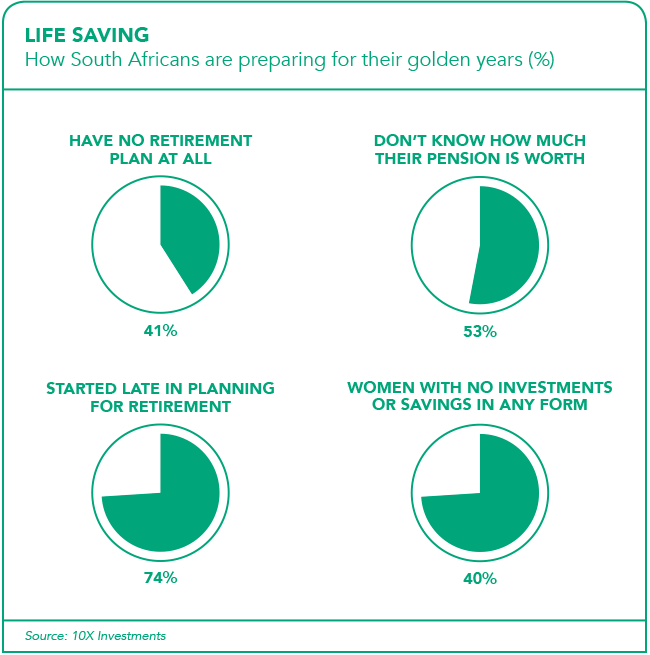

The way that the industry traditionally measures whether someone can retire comfortably is ‘probably terribly flawed’, she says. ‘It employs a First World assumption that when one reaches retirement age, their children have been educated, moved out of the house, and have their own full-time employment.’ The assumption being that to retire comfortably, all you have to do is accumulate enough savings to replace 75% of your final income before retiring for the next 20 years. According to Cabot-Alletzhauser, ‘by that measure, only 6% of South Africans can theoretically retire comfortably’, a concept that is far removed from most Africans’ reality. ‘Most African families see support in retirement as simply a continuation of the intergenerational support that a family provides to each member. At the start, the elderly may take care of the children so that parents can work. But when the time comes for more frail-care support, the roles reverse and the cared-for now starts taking care of the carer,’ she says.

In the past decade, the pension space in South Africa has seen a significant shift from stand-alone funds to umbrella funds – and this is continuing, says Davison. A key advantage of this development is that umbrella funds have the budget to invest in technology. ‘The drive to lower costs has resulted in significant investment in technology to drive efficiencies,’ he adds. To this end, some processes in the largest umbrella funds are now automated to a much greater degree, improving processing times and delivering substantially faster turnaround times.

Moreover, online access to savings values, which are updated daily, and the ability to process certain transactions, such as withdrawal claims, switches and updating of personal information, are now common features of umbrella funds. For the most part this helps members, but it can heighten emotions when volatility in the markets occurs, often with detrimental consequences if panic sets in.

The introduction of tech has had a material impact on the retirement fund industry, says Gouws. Improved technology has made investment and member administrators more effective from a process and cost perspective. ‘Economies of scale are not only achieved by having larger assets, but also through greater administrative process efficiencies,’ he says. ‘Investment administrators are able to deal with a broader range of instruments, which allows for more diversified investment portfolios and strategies. This offers the potential for enhanced portfolio returns over time,’ according to Gouws.

Technology has also made life easier for member administrators, trustees and management committees. ‘It has allowed member administrators to administer more advanced investment strategies on behalf of retirement funds and its members, such as life-stage models. All fund-related member and investment reporting [is] now available in real time and through various channels and access points for boards of trustees and management committees of retirement funds,’ says Gouws.

The advent of so-called robo-advisers – essentially digital financial advisers that provide web-based portfolio management with minimal human intervention – are a trendy new fintech concept, notes Cabot-Alletzhauser. But robo-advisers do not provide employee benefit advice, nor will they balance your budget or encourage you to preserve your pension savings, she warns. Not yet, anyway. ‘This is the direction the industry needs to move in,’ she says. ‘Towards a holistic framework for full-life financial planning.’

Cabot-Alletzhauser uses Singapore’s intervention into pension savings as an example. Even before it achieved independence in 1965, Singapore’s government had a system where people had to contribute a minimum monthly sum towards retirement, and the government matched it and encouraged the public to use the rest of the money they would have put towards retirement to cover other costs, such as housing, education and medical requirements. ‘This asset-based development strategy was seen as a key aspect to self-determination, which ranks highly on Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, and a financial capability development,’ says Cabot-Alletzhauser. At the time, housing was seen as a top priority. Today, Singapore has one of the highest savings rates globally and ranks among the best in the world when it comes to financial literacy.

Drawing a broader range of LSM [Living Standards Measure] groups into the formal retirement savings system will require enhanced accessibility to savings vehicles and relevant information, Gouws points out. ‘This speaks to the convenience of making regular contributions, allowing for lower minimum contribution levels and access to transactional functionality,’ he says. ‘Education at primary and secondary school level to enhance financial literacy will create greater awareness of the need to save for retirement from as early as possible. Furthermore, special incentives to save, aimed at lower income levels, could assist in enticing individuals to save for retirement.’

The use of interactive learning content and technologies to improve financial literacy and the availability of applications on mobile devices will be critical to get the younger generation more engaged in the process of saving for retirement. Self-help service options and electronic applications on mobile devices will also assist in inspiring the younger generation to save for retirement, says Gouws. It’s difficult to pinpoint just one area as there are many areas where technology is driving change. ‘A lot of work is happening in the user experience space and I do expect this to make a big impact,’ says Davison.

However, technology alone is not enough to reshape the retirement landscape in South Africa and the rest of Africa. A new contract between employers and employees is required, stresses Cabot-Alletzhauser. One that starts at the beginning of the contracting with an employee and is able to highlight both the long- and short-term impact of benefits an employer has to offer. ‘The pension fund should be seen as just one of those benefits, but if an individual can see that the employer is offering a holistic solution that provides a guided financial planning framework with significant cost efficiencies throughout their life journey, we believe there will be a more significant buy-in,’ she says. ‘We’re moving towards a world where more and more financial advice is needed by a population that has fewer and fewer resources to afford it.’

This leaves us with limited options, says Cabot-Alletzhauser. ‘Digital advice must step up to the plate in providing a viable means of reaching a broader population. But this is an industry that also needs to come of age before it will be able to achieve this. Right now, the bulk of online digital advisers and robo-advisers in South Africa are simple calculators that offer a one-size-fits-all approach. To ensure that people retire comfortably, we need to do much more than just provide our populations with financial support.

‘We need to provide an integrated framework of support for community-based and home-based frail-care solutions,’ she says. ‘As urban migration fragments the traditional multi-generational family support systems in Africa, money alone won’t be enough.’