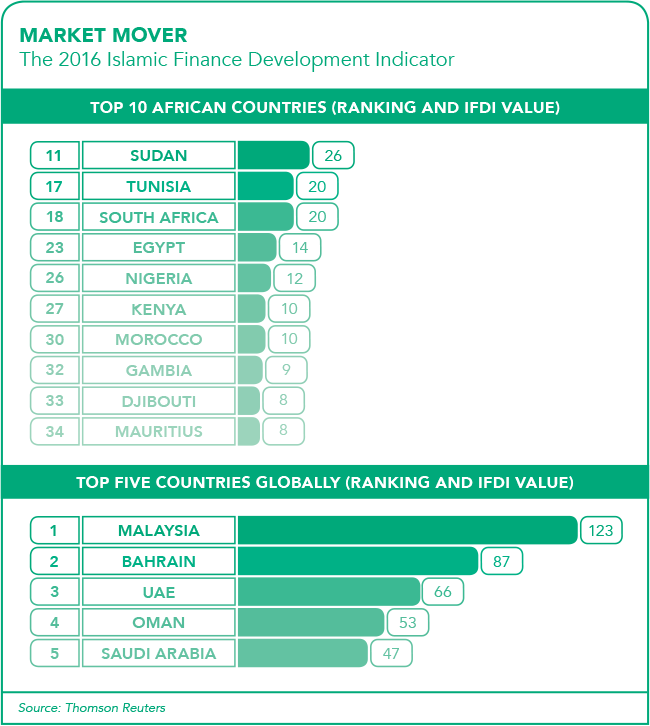

While sub-Saharan Africa accounts for just a fraction of the world’s total Islamic financial assets – valued at US$2 trillion in 2014, according to Thomson Reuters – there is widespread optimism regarding its growth. Recent headlines call the continent ‘Islamic banking’s new frontier’ and predict ‘impetus for growth’, a ‘promising future’ and a ‘huge untapped market’.

Guided by the principles of Islamic law (shariah), the financial system is based on risk sharing and prohibits the earning and charging of interest.

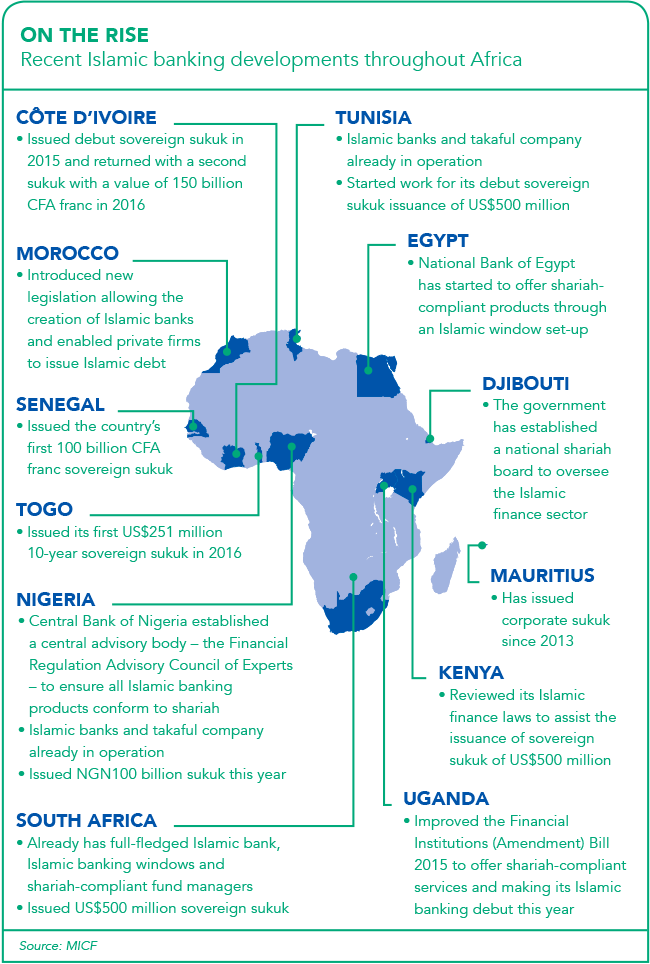

Numerous African jurisdictions, including, Kenya, Morocco, Nigeria, Senegal and South Africa, have established legal and regulatory frameworks to facilitate Islamic banking. As a result, major financial institutions are offering more and increasingly sophisticated shariah-compliant products and services in the region.

One of the drawcards is that Islamic finance can serve as an instrument of financial inclusion for unbanked Muslims in sub-Saharan Africa who, according to a World Bank study, are less likely to have a formal bank account than non-Muslims and cite their religion as a barrier.

Furthermore, Islamic finance makes investing in Africa more attractive to Muslim investors from the Middle East, particularly the oil-rich Gulf States. It also presents a tool – in the form of sovereign sukuk, the Islamic version of bonds – to raise funds for infrastructure and other development projects.

‘On a continent that nearly a billion people call home, approximately 50% of them are adherents of the Islamic faith,’ says Amman Muhammad, CEO of Islamic banking at First National Bank (FNB). ‘This statistic in its own right is attractive enough for any financial institution to look at Africa as a destination for Islamic financial services.’ He is at the forefront of promoting Islamic banking and finance at an institutional, industry and sovereign level in Africa, and became the first African to be awarded the title of ‘Upcoming Personality in Global Islamic Finance’ at the Global Islamic Finance Awards in Bahrain in 2015.

Keen to dispel misconceptions about Islamic banking, he says it must be regarded as an alternative to mainstream banking as it’s available to anyone, irrespective of their faith, and founded on principles of ethics and values.

‘Many people of other faiths are beginning to appreciate that their money and investments should be handled in a socially responsible manner. Islamic banking offers that assurance of social responsibility,’ he says.

‘Sometimes the more practical elements of Islamic banking are equally attractive to customers of other faiths. In a recent conversation I had with a single mother of two, who was in the process of financing a new car, the ability to effectively budget in these uncertain economic times was of prime importance to her. With regularly fluctuating interest rates, this single mother chose to use Islamic banking because it allowed her the ability to fix a rate for the duration of her vehicle finance deal.’

Islamic vehicle and asset finance is based on the so-called ‘ijarah’ (lease) agreement, where the bank purchases an asset for the client, allowing usage for a fixed rental payment. Ownership remains with the bank but is gradually transferred to the client.

The World Bank explains that Islamic finance ‘promotes risk sharing, connects the financial sector with the real economy, and emphasises financial inclusion and social welfare. The key point to bear in mind is that Islamic law doesn’t recognise money and money instruments as a commodity but merely as a medium of exchange. Hence any return must be tied to an asset, or participation and risk-taking in a joint enterprise (such as partnerships)’.

Professional services firm EY, which has established the Centre in Islamic Finance for Africa in Johannesburg, lists the key principles that underpin Islamic finance as prohibition of interest [‘riba’], excessive uncertainty and gambling; preclusion of investment in particular industries within the food and beverage sector (entertainment, tobacco, alcohol, pornography), arms manufacturing and conventional finance; that all transactions should be supported by productive economic activity; and risks and rewards should be shared between all participants.

Some practicalities of Islamic banking remain a challenge for financial institutions in Africa, mainly because they are forbidden to charge fees or interest for money lending and other services. The interpretation of shariah compliance sometimes differs according to the geographic region, which complicates the public understanding and uptake of Islamic banking products.

‘Despite the projected asset growth and the introduction of new Islamic initiatives in a number of countries, the profitability of Islamic banking continues to lag behind that of conventional banking in the same markets,’ EY said in a media release. ‘These issues have prompted several institutions to initiate wide-ranging transformation programmes that will see the industry take the next step in its evolution from being a niche market to a profitable, service-orientated industry attracting customers for product innovation and value-added services.’

Africa is home to more than 50 Islamic financial institutions out of 600 globally, according to the Islamic Corporation for the Development of the Private Sector. In sub-Saharan Africa, Al Baraka Bank of South Africa has the highest value of total Islamic assets under management (US$327 million), states a global Thomson Reuters ranking.

Overall, however, Al Baraka ranks just seventh – after Egypt’s Faisal Islamic Bank (US$7.09 billion) and significantly behind the top Islamic bank, Al Rajhi Bank, which is based in Saudi Arabia and holds US$84.12 billion in total Islamic assets.

An increasing number of conventional banks are offering shariah compliance through what is called ‘Islamic windows’, including Nigeria’s FinBank, Kenya’s First Community Bank and, in South Africa, Absa, FNB and Standard Bank.

‘We are on a journey of developing this capability across all our operations as part of our 2020 vision,’ says Ameen Hassen, head of shariah banking at Standard Bank, which operates in 20 African countries.

‘In response to a growing call from our customers, we are in the process of developing shariah-compliant banking solutions across every type of service offered by the bank.’

According to Uwaiz Jassat, Islamic banking head at Absa (which is part of the Barclays Africa group): ‘Islamic banking was launched in Kenya in 2005, in South Africa in 2006 and 2010 in Tanzania as a response to customer needs.’ Islamic banking has grown exponentially in all the markets in which Barclays Africa operates, he says, although figures suggest the penetration is still below 10%.

‘That means there is still a massive opportunity to attract new customers to the Islamic propositions. This has also attracted new entrants into the market looking to capture a share of this untapped opportunity.’

In South Africa, FNB offers the widest spectrum of shariah-compliant products to both retail and business clients. ‘Our product range is not complicated, yet we meet the needs of our customer base by offering day-to-day transactional banking products that cover a variety of segments, from entry-level banking all the way through to complex commercial banking,’ says Muhammad.

‘Furthermore, we are one of the only banks in sub-Saharan Africa to offer both our business and personal customer base the convenient Islamic Savings Pocket. This account pays an attractive monthly profit share to the customer and is available on demand.

‘The newest addition to our product set is “takaful” or, in other words, Islamic insurance – for now we offer a comprehensive short-term coverage that is suitable for home, motor and business. In the fiduciary space, we offer Islamic wills, with Islamic trusts soon to follow.’

In addition, FNB also provides shariah-compliant property finance on a ‘diminishing musharaka’ agreement, which allows individual and commercial clients to purchase the bank’s portion of the property they want financed over a period of up to 20 years.

‘We were the first bank globally in 2017 to structure sukuk, which is best described as an infrastructure development Islamic bond that yields profit as opposed to interest, for the African Finance Corporation,’ according to Muhammad.

Three years previously, Standard Bank was the lead arranger for South Africa’s inaugural sukuk, which was introduced by the country’s National Treasury to broaden the investor base and diversify the sources of infrastructure funding. The US$500 million transaction was more than four times oversubscribed, with an order book of US$2.2 billion.

Other African nations have also issued their debut sukuk – Senegal (2014), Côte d’Ivoire (2015), Togo (2016) and Nigeria (2017). However, some critics say that Islamic finance and instruments such as sukuk may strengthen calls for stricter shariah laws to be imposed on the continent.

Much research and education is still required, and regulatory issues need to be solved before Islamic finance can live up to its promise of socially inclusive, responsible banking that can boost infrastructure and prosperity across Africa.