With the election of Donald Trump, it looks like the US’ renewable energy policy could lose steam, at least temporarily, in the face of an apathetic presidency. This may in turn have effects on the bases of power generation worldwide, as shale oil, tar sands and coal supply increases. Nevertheless, the global evolution of off- and on-grid electricity production (towards renewables) is unlikely to be halted by recent developments – analysts at EY estimate that by 2035, US$6 trillion will be invested in renewable energy infrastructure worldwide, compared to US$2.75 trillion for conventional sources.

There is a strong environmental case for renewables, and constant technological refinements mean that these forms of power generation also make compelling economic sense. For mines in Africa, their value is particularly clear.

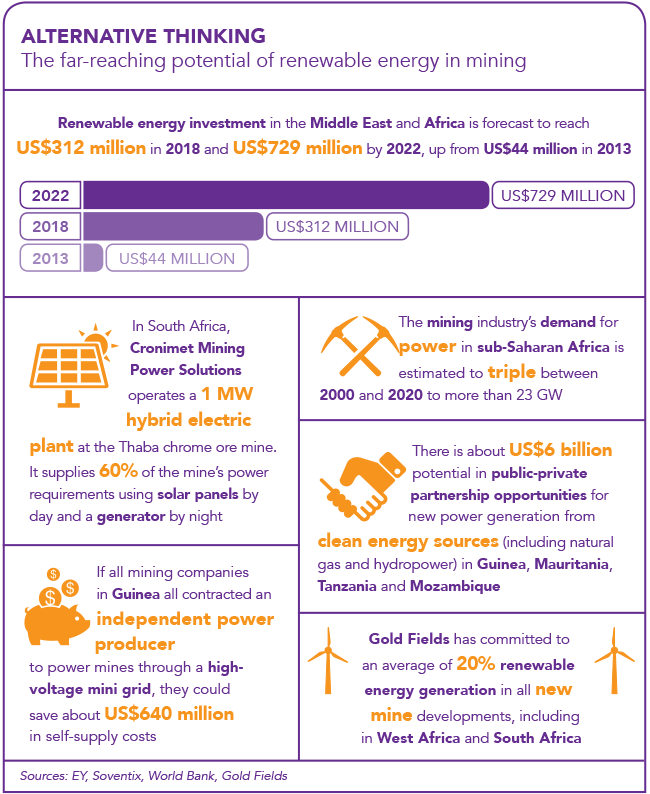

The World Bank has predicted that by 2020, African mines will have a total power demand in excess of 23 GW, and in countries such as Liberia, Guinea and Mozambique, the requirement from mining will exceed all other demand combined. ‘For this reason, mining companies have been looking for renewable solutions that will feed their mines with the power supply needed for operations and at a locked-in price over the long-term, as well as potentially provide power for the surrounding area/community,’ says Dinesh Buldoo, director of power transmission and distribution at WSP Parsons Brinckerhoff Africa.

In the past, major mines around Africa have relied either on stable grid generation and favourable supply contracts, or on diesel-powered generation for locations away from the grid. But across the continent, grid infrastructure is now struggling to keep pace with domestic demand, which needs to be met to improve living standards, ensure political stability and stimulate economic growth.

In the effort to maintain their social licence to operate, some mining companies are keenly aware of this gap. It is no longer sustainable to draw large amounts of grid power while nearby communities go without basic electricity provision or experience constant brownouts – and many governments are no longer prepared to strike the kind of long-term supply agreements that characterised the period from 1960 to 2000. These are just some of the factors driving a turn towards renewables in African mining. Others include the inherent attractions of the technology not to mention the excellent conditions for renewables generation across the continent.

Different African environments lend themselves exceptionally well to solar, wind, biogeneration and local hydropower systems, particularly in hybrid set-ups with diesel or gas for peak-load generation.

Solar technologies, for example, can be cost effective in a way that would be impossible in northern Europe. New leasing models, or power purchasing agreements with independent renewable generators, have also made renewables accessible to mining houses without the steep initial costs (and risks) that deterred many in previous years.

Analysts at BMI Research calculated that in 2014, the cost of electricity from a diesel generator came to an average of US$0.28 to US$0.32 per kilowatt hour, compared to US$0.17/kWh for solar and US$0.14/kWh for wind. There’s no doubt that these sources are seen as increasingly viable for miners worldwide – law firm Chadbourne estimates that the period to 2020 will see US$20 billion in mining renewables investment.

‘There is certainly a need for governments to create openly engaging and enabling environments for renewable energy projects in Africa. This needs to be led by steadfast policy to incite investor confidence,’ says Buldoo.

‘In terms of the policy frameworks themselves, keen consideration should be given – though not exclusively – to tax and carbon-tax breaks, subsidies and allowing mining companies to sell excess power capacity back into the grid. Essentially these policies need to be conscripted with the aim of helping the alternative energy sector grow – and to overcome upfront capital costs on individual projects towards long-term gains.’

Internationally, South America has been host to some of the most noteworthy recent developments. Chilean national copper producer Codelco has struck an agreement with an independent solar facility to provide a substantial 51.8 GW/h of power to its Energía Llaima copper mine – the turn to renewables replaces 85% of the mine’s diesel demand and saves it the equivalent of two months of conventional fuel spending per year.

Similarly in Canada, major miner Rio Tinto has developed a 9 MW wind farm for its Diavik diamond mine in the Arctic – the new power source reduces its diesel use by more than 4 million litres a year and carbon emissions by around 12 000 tons annually.

There’s plenty happening in Africa too. In West Africa, Ghana, to an extent, is leading the way in developing a renewables-friendly policy environment. Faced with a lack of capacity on the national grid, as the country’s main supply of power at Lake Volta (itself a renewable source) has declined, Ghana has mandated that all mines will have to generate at least 10% of their electricity from renewables by 2020. A number have already installed local hydro or solar capacity.

Nearby, in Liberia, UK-based Hummingbird Resources has recently announced the completion of a pre-feasibility study [PFS] for renewable power at its Dugbe gold project. The company is exploring the installation of hydoelectric plants generating 10 MW to 30 MW of power.

Hummingbird CEO Dan Betts argues that ‘power costs make up over a third of our total process expenditure at Dugbe, and finding savings in this area will have positive implications to the project’s economics. We had been using an estimate of US$0.28/kWh for rented diesel power in the PFS.

‘Taking the total capex and opex for the plant, over the current 20-year mine life, gives you a theoretical cost of US$0.05/kWh’.

In Mauritania, to the north-west, hybrid wind power looks set to play a major role at iron ore mines operated by the Société Nationale Industrielle et Minières (SNIM). These are some of the highest-producing mines on the continent, exporting more than 12 metric tons of ore per year.

SNIM awarded a tender to France’s Vergnet Group for the installation of a 5 MW hybrid wind/diesel plant – produces 19 GW h/year of electricity, saving SNIM around 4 800 tons of fuel annually.

Similarly, in East Africa, Acacia Mining is looking to use solar power (to reduce its reliance on Tanzania’s national grid) for production at the country’s premier Bulyanhulu mine. Also in Tanzania, although on a smaller scale, Shanta Mining has just reached agreement with one of the region’s major solar leasing firms, Redavia, to increase solar capacity at its New Luika gold mine.

The installation will take the mine’s hybrid solar capacity to approximately 670 kW per year, with an anticipated annual saving of around 250 000 litres of fuel once the plant is complete.

In South Africa, much attention has been given to the use of hybrid solar power at Cronimet Mining’s operation in the Thabazimbi region, where a 1 MW plant was installed some years ago, when it was the largest of its kind. But this looks likely to be dwarfed by future builds – major producer Gold Fields is inviting bids for a 40 MW solar plant to power its South Deep mine. The miner is also looking to implement a policy requiring at least 20% of renewable power for all its new projects. In comments to an Energy and Mines forum, Gold Fields head of carbon and energy Tsakani Mthombeni said data suggests ‘a marked reduction in cost for certain renewable energy technologies, as well as increasing funding for these renewables. This is something mining companies could be and are taking advantage of’.

In addition to a host of reputable sites, the recent explosion of Africa-focused conferences on renewable mining energy suggest how seriously the industry is taking technologies such as solar and wind.

This is also indicated by the rapid growth of companies that cater to mines, either through the building or hiring of plants at a particular operation, or through the construction of standalone renewables generation with an eye on mining customers.

Firms such as France’s Vergnet and EREN Group, and Germany’s Redavia and Soventix are quickly making African mining houses a principal focus of their business and pricing models. These companies have established a network of offices on the continent, and this market will hopefully be joined by an increasing number of local competitors with the skills to install reliable renewable plants – similar to what is happening in South Africa at present.

Although renewables-only mines are mostly still an idea for the future, it’s now not unthinkable that in the next decade, some African operations will draw most of their power from sustainable sources. The biggest steps forward may come when renewables are better incorporated into national grids – helping to solve a number of industrial and domestic energy problems, and making other generation methods more readily available for peak loads.

Renewables currently make up around 23% of total power generation in SADC countries and, given the region’s potential, it is expected that this will increase. The case for renewables in mining has already been widely accepted. With an estimated 1 080 TWh of hydropower and 20 000 TWh of solar energy available across SADC – and similar amounts in other African sub-regions – it simply isn’t hard to see why.