In early 2019 Juwi Renewable Energies signed a deal with JSE-listed Orion Minerals to investigate a renewable-energy generation solution for the Prieska Zinc Copper project. They settled on a wind/solar hybrid power system that would generate and supply 35 MW of electricity, with Juwi describing hybrid systems as being ‘at the forefront of transforming the remote power-generation sector and the resource industry into one with a sustainable future, as they offer emission-free low-cost energy’.

‘Remote’ was not a word he used lightly. Prieska is – according to the town’s own website – ‘literally in the middle of nowhere’: a stupendously boring and dusty two-hour drive from Kimberley in South Africa’s Northern Cape and just more than an hour from the next-most interesting town, Putsonderwater (Afrikaans for ‘well without water’). When you hear that Prieska’s own name comes from a Khoisan word meaning ‘place of the lost she-goat’, you start to see just how remote it really is.

Yet, as in many similar parts of Africa, that’s exactly why Prieska is so perfect for this kind of power-generating system. ‘The region has the highest irradiance levels in the country and is very well situated for wind farms,’ says Orion CEO and MD Errol Smart. ‘It is already a well-established renewable-energy generation region with 190 MW of solar power plants in operation and 240 MW of wind power under construction adjacent to our Prieska project. The opportunity can only improve our power-supply security while lessening the burden on the national electricity grid and reducing our carbon and water footprint.’

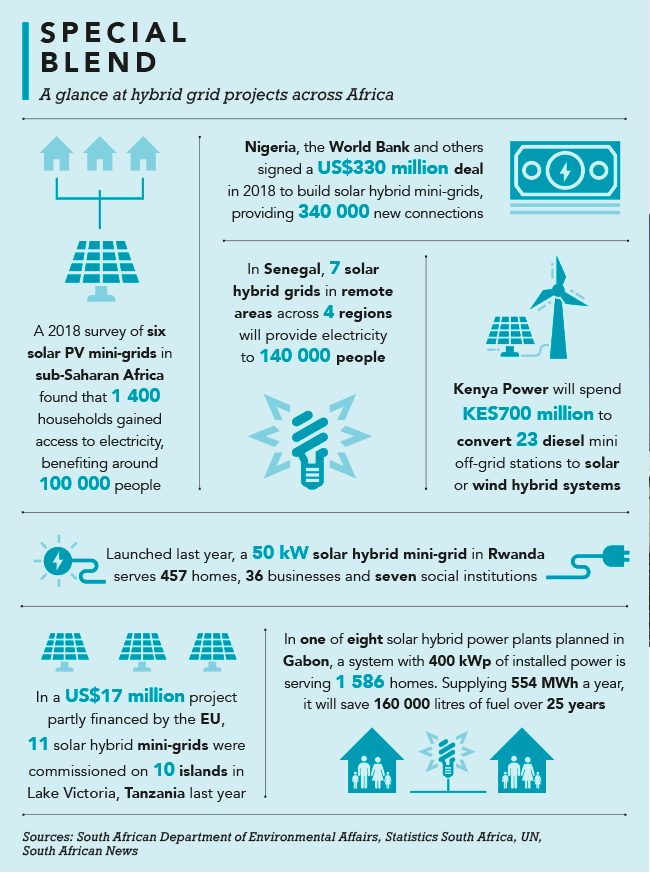

Similar projects are under way or already in operation across Africa, as companies and municipalities in remote areas look to marry one form of renewable energy with another to create an overall solution. These hybrids could be any kind of combination. In Niger, a new 19 MW hybrid plant in Agadez consists of solar panels producing 13 MW along with diesel generators with a capacity of 6 MW.

In the DRC, meanwhile, power company Nuru recently installed a 1.3 MW mini hybrid solar/battery plant in the eastern city of Goma, while in Sierra Leone, local start-up Light Salone is rolling out a series of small-scale solar/wind hybrid plants. Light Salone’s project, called Sowind Technology, is particularly creative: it includes a plastic lantern, a small-scale hydro generator and charging telecentres, and it’s built from cheaply sourced recycled materials. ‘Over 85% of citizens in Sierra Leone and more than 99% of rural communities have no access to electricity. Hospitals, schools, youth centres and small businesses do not function effectively because of the inconsistency of electricity supply,’ Light Salone co-founder Mohamed Kamara says in an interview with Disrupt Africa.

It’s a similar story in Gabon, where work recently began on a solar/diesel hybrid power plant in Ndjolé, a remote town on the Ogooué river. That project will consist of 1 445 solar panels producing a collective 400 kWp of electricity, supported by a diesel generator. It’s one in a series of eight hybrid projects that Gabon’s Deposit and Consignment Fund is rolling out across the country. On completion, they will have a combined capacity of 2.2 MW.

The drivers behind this trend towards hybrid power systems become clear as soon as you look at a map. Agadez, Goma and Ndjolé all either lack access to a stable existing power grid or (like Prieska) are situated in the middle of nowhere. It’s why Africa’s mines are increasingly turning to hybrid solutions too.

Power supply at the continent’s remote mines is often off-grid and is usually sourced from fossil fuels, diesel or heavy fuel oil – all of which are expensive to transport (which is why electricity makes up about 20% to 30% of many African mines’ operational costs).

‘One of the reasons mines require hybrid energy rather than being entirely dependent on renewables or being entirely dependent on diesel is that mines operate normally on a 24/7 basis 365 days a year and are very dependent on continuous operations,’ adds Juwi’s global head of hybrid, David Manning. ‘The start-up on a mine site can take several hours, shutdown can take several hours, and any period of no power is extremely detrimental to operations.’

That’s why, historically, mines were hesitant to look at pure renewable solutions, which depend on daylight (for solar) or favourable weather (for wind). ‘Hybrid bridges the gap,’ Manning says in an online post. ‘It allows mines to run renewables when the sun shines and when there is wind but to fall back on diesel and battery storage for reliability. And as battery technology is becoming cheaper, we are seeing more installations where batteries are viable. Batteries enable larger solar or wind systems, and [they] enable mines to transition seamlessly from renewable energy across to diesel without interruption to supply.’

Further enabling that seamless transition from hybrid to backup and back again, Juwi has also developed a system to integrate the various power sources.

‘What we call the hybrid controller is the heart of the operation, and designing and implementing it properly is of paramount importance,’ says Manning. ‘Juwi has put a lot of engineering and development into that process, ensuring that all sources in the power system work seamlessly and balance solar, diesel, wind or battery, so that there is zero interruption to supply. It is all about maintaining voltage, frequency and power factor no matter if the sun shines, the wind blows, or a large mill ramps up.’

Juwi’s hybrid supervisory control and data acquisition (SCADA) system provides visibility of all generation assets and offers greater control of and more real-time clarity on power-generation costs. ‘What we found is that other systems provide only separated views or systems; one for solar, one for diesel and maybe wind and battery, but not integrated properly and with high resolution. What the Juwi hybrid SCADA does is bring it all together into one system that monitors and combines everything and gives the operator easy access,’ says Manning.

But hybrid systems aren’t only good for small-scale micro-grids. In February, Kenya began construction on Africa’s first hybrid power plant. Meru County power park will ultimately provide more than 200 000 households with up to 80 MW of affordable renewable energy, through a large-scale facility that will combine wind, solar PV and battery storage. Up to 20 wind turbines and more than 40 000 solar panels will be installed in what is estimated to be a US$145 million to US$150 million investment.

The project is being developed in a public-private partnership initiative between the Meru County Investment and Development Corporation and global renewable energy development company Windlab. On completion in 2021, it will be operated under a joint development agreement.

‘As Kenya moves to implement the medium-term Big Four agenda, promotion of predictable and sustainable renewable energy is key to guarantee successful realisation of the manufacturing pillar. The project would help shore up manufacturing in the country,’ says Windlab’s global CEO Roger Price, pointing to the country’s quadruple development goals of promoting food security, universal health coverage, affordable housing and manufacturing.

He says that more than 70% of Kenya’s electricity is already generated from renewable clean-energy sources. And Meru provides a perfect example of why that is.

The town of Meru lies barely 8 km north of the equator at an altitude of about 1 500m. It’s surrounded by forests and farms, in what an early Welsh missionary once described as a place of ‘hills, valleys and immeasurable streams’. Meru enjoys yearlong sunshine and endures strong winds. It’s the perfect place for both solar and wind energy.

Instead of choosing one or the other to provide reliable, renewable electricity for its people, Meru County – like Prieska and dozens of other remote places across Africa – chose a hybrid instead.