Egypt, Kenya, Nigeria and South Africa have all recently taken major steps towards new or expanded nuclear power programmes. While critics and doubters remain obdurate, there may be a better match between nuclear power and African development than many would have thought.

Nuclear power, long seen as not really ‘clean’ because of the problems associated with radioactive waste disposal, has in recent years acquired ‘green’ credentials. Nuclear generation is a carbon-free method of producing electricity, and in the 21st century this has become an important positive attribute.

According to Viktor Polikarpov, Russian nuclear firm Rosatom’s vice-president for Southern Africa: ‘Nuclear energy has saved the environment from countless carbon emissions. If South Africa’s Koeberg nuclear reactor had been a coal-fired plant, it would use six train loads of coal per day. In fact it uses only one truck load of nuclear fuel per year.’

In Africa, Egypt is leading the nuclear race. The country has had plans to build a nuclear power plant at El Dabaa since the 1980s. A first attempt was aborted due to concerns about the safety of the technology after the 1989 Chernobyl explosion incident in the then Soviet Union. But since Chernobyl, a third generation of nuclear reactors has been developed with safety mechanisms that operate automatically instead of relying on human action.

A further feature of third-generation reactors is standardisation in design, which means that approvals (especially from the global regulator, the International Atomic Energy Association) are much more straight-forward. This makes it possible to purchase a reactor ‘off the shelf’, using a proven design developed by the likes of Rosatom, France’s Areva, Korea Electric Power Corporation and China General Nuclear Power Group.

These firms have assiduously courted African governments in recent years, and none more so than Rosatom. It was awarded the Egyptian contract and, in September, signed an agreement with Tunisia. Rosatom is also the favourite to lead South Africa’s anticipated nuclear build.

While critics mutter about undue influence, it has to be pointed out that Africa’s much-heralded renewable energy programmes have also been driven by global policy networks centred on countries with an interest rooted in the health of their own domestic industries. The nuclear advocacy practiced by countries such as France and Russia simply parallels the renewable energy advocacy of Germany and the US.

The Egyptian project now appears to be going ahead. Last year, the country’s President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi announced that the plant would be constructed in partnership with Russia and that the first of four reactors would come on-stream in 2024. Earlier this year a Russian loan facility of US$25 billion was declared, covering 85% of the anticipated costs.

In 2016, Kenya announced nuclear energy pacts with Russia and South Korea, following a similar arrangement with China last year. Such pacts are an essential stepping stone as they open the way for the skills transfers – in areas such as reactor and nuclear waste management – necessary for the safe use of the technology. According to South Africa’s power utility Eskom, it takes at least six years to train a nuclear plant operator.

South Africa has already put in place similar agreements over the past four years and recently requested for proposals for 9 600 MW of nuclear power generation capacity. This next step in the country’s programme – which has been mired in political controversy – has been touted as a measure to put concrete options on the table (with costings) before a final decision can be made.

At present, South Africa is the only nuclear power plant operator on the continent. The 1 800 MW Koeberg plant near Cape Town was finished under the apartheid government in the mid-1980s.

Domestic criticism at the time was vociferous, although this was so inextricably intertwined with general opposition to the apartheid regime’s policies and strategic plans (which included nuclear weaponry) as to leave an ambiguous legacy. Nevertheless, the revival of South Africa’s nuclear ambitions in 2010 came as a surprise to many observers.

Nigeria is probably not as far down the line as the other major African economies. The country’s energy sector is heavily embroiled in sorting out a number of issues around the oil industry and its gas-fired power plant spin-off.

However, Nigeria too is co-operating with Russia’s Rosatom. Last year, the Nigerian Atomic Energy Commission announced that it had selected two sites for the building of nuclear power plants, each with a capacity of 2 400 MW at an estimated cost of US$20 billion. A unique Nigerian argument in favour of nuclear power is that existing gas plants have been bedevilled by pipeline breakages as entrepreneurial local gangsters have sought to tap the resource and sell it in local markets.

The nuclear energy industry has experienced extreme peaks and troughs since the technology was opened to the world in the wake of US President Dwight D Eisenhower’s 1953 ‘Atoms for Peace’ speech to the UN.

The technology has sharply divided those who saw it as the harbinger of a better age for humanity – premised on an abundance of cheap electrical power – and those who considered it to contain the seeds of destruction of the species and indeed much of the rest of the planet.

The 2011 Fukushima nuclear disaster in Japan, initiated by an earthquake and followed by a tsunami, appeared to many as a blow from which the industry was unlikely to recover. Within a year, Japan had shut down all but two of its 50 nuclear reactors. Germany accelerated existing plans to phase out nuclear power; Italy banned all further nuclear construction; and France announced it would reduce nuclear usage by a third.

In tandem with the tumbling prices of renewables, such as solar and wind power, it appeared that the nuclear age was winding down, with its promise of human betterment having been proven to be largely chimeric. By 2015, however, nuclear power had made a remarkable resurgence. In a generally stagnant commodities market, uranium enjoyed an excellent year. Bloomberg reported that uranium supply contracts had risen from about US$35 per pound to US$50 in 2015.

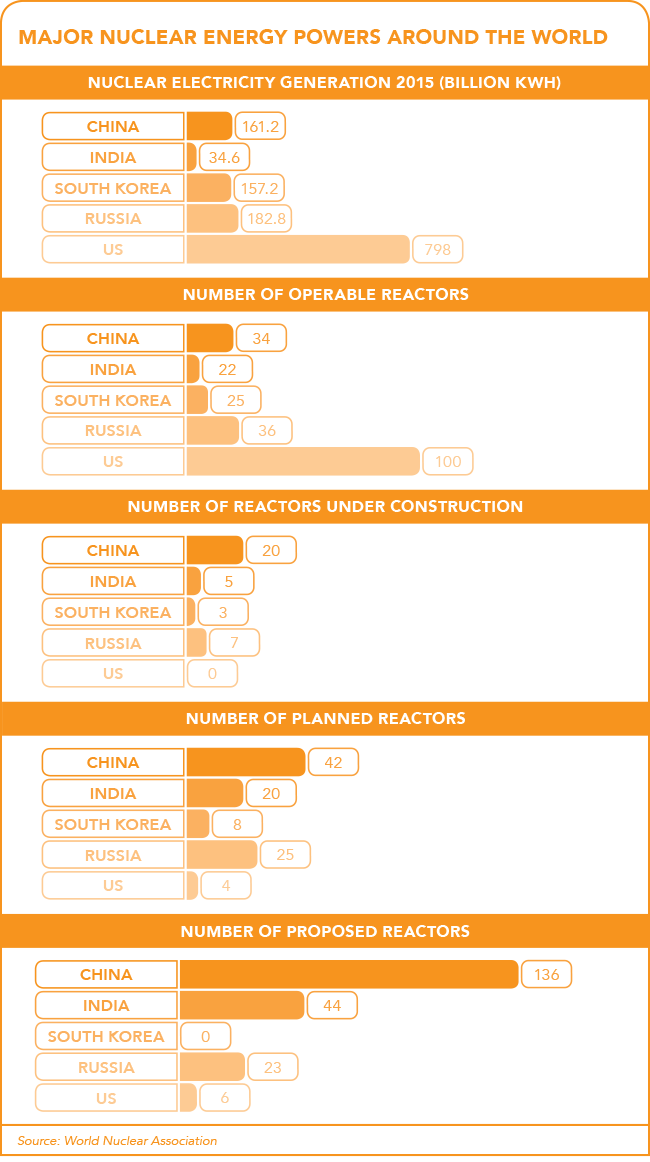

The main driver was, as so often in the commodities market, Chinese demand. The country currently has 34 operating nuclear reactors, an additional 42 planned and 136 at the proposal stage. Uranium miners are currently producing less than power generation companies are using, which means that the industry is burning through existing stockpiles.

‘African leaders have realised that in order to grow their economies they need to beneficiate their resources themselves, rather than export them as raw materials,’ says Polikarpov. ‘This cannot be done without sufficient baseload electricity.’ He argues that a choice between nuclear and renewable energy rests on a false dichotomy – it’s not either or.

‘Every country needs an energy mix. South Africa’s geographic and climatic features allow actively developing solar, wind and tidal energy, which would be a good solution for many small households and farms,’ he says. ‘However, it’s vital to have a source of energy that can provide baseload power as and when it is needed.’

Nuclear power has one great advantage over renewables. It is a reliable generator of baseload power on a large scale. Critics in South Africa and Egypt have objected that there is insufficient demand in either country to justify using the technology. However, if accelerated industrialisation is to be the basis for Africa’s development, energy planning around current levels of use is simply shortsighted, and refusal to consider a qualitative leap in generation capacity is likely to result in a self-fulfilling prophecy. If countries don’t construct plants because there is insufficient industrial demand now, they can be sure there will be insufficient demand when it is needed to boost economies and create jobs.

Perhaps the most coherent objections to nuclear power revolve around its costs. Nuclear, like renewables, is a form of power generation where most costs are incurred in construction. Once the plant is built, it costs relatively little to keep it running. This can be contrasted with coal- and gas-fired power stations where the ongoing cost of purchasing fuel is a permanent and built-in consideration.

There is much misrepresentation and obfuscation around price comparisons between different technologies. Even seemingly objective indicators such as predictions of future electricity price per kilowatt hour need to be considered cautiously. With fossil fuels, these involve difficult-to-predict variables such as coal and gas prices 10 years down the line. With wind power, boilerplate capacities are very seldom achieved while solar power cannot, given present technology, meet demand at night.

What does seem worth observing is that nuclear builds have in recent years had a good reputation for coming in at projected constructions costs. Advocates of the technology, such as Eskom CEO Brian Molefe, insist that nuclear is the lowest cost option.

Molefe, however, somewhat undermined his case by referring to the present generation costs of the Koeberg plant, completed in 1985. The cost of capital is a critical variable.

Rosatom’s Egyptian loan facility has been offered at a mere 3% annual interest with payments beginning only in 2029. This is comforting but the sums at risk are still huge. Suggestions that South Africa’s programme could cost ‘ZAR1 trillion’ may smack of scaremongering but even (a perhaps more realistic) ZAR500 billion is still equivalent to half the country’s annual national budget.

In August, Eskom released a statement in which it asserted that ‘South Africa has committed to building new nuclear power plants in its bid to lower carbon emissions, and in order to generate cheaper electricity and thereby further stimulate economic growth’.

Such a statement, combined with the opening of the request for proposals process, means the debate can only intensify in the months to come.

Could nuclear power be part of the solution to Africa’s energy deficit?