The Gates Foundation’s most recent annual letter included a satellite image of Africa taken during the night-time. To the north, Europe glittered with millions and millions of lights. But Africa, our vast continent, was left largely in the dark.

‘Africa has made extraordinary progress in recent decades,’ Bill and Melinda Gates wrote in their letter. ‘It is one of the fastest-growing regions of the world, with modern cities, hundreds of millions of mobile phone users, growing internet access and a vibrant middle class. But as you can see from the areas without lights, that prosperity has not reached everyone. In fact, of the nearly 1 billion people in sub-Saharan Africa, seven out of every 10 of them live in the dark, without electricity. The majority of them live in rural areas.’

Bill Gates argued, passionately and convincingly, that a lack of cheap, clean energy (‘lights, refrigerators, skyscrapers, elevators, air conditioning, cars, planes, and all the other things that make up modern life’ as he put it) is stunting Africa’s development.

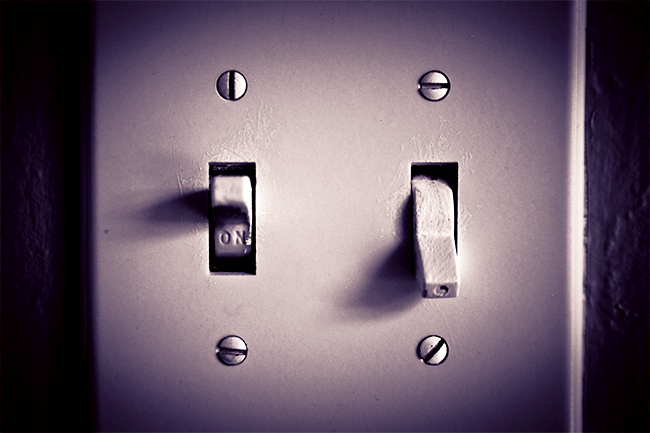

It’s hard to disagree. Throughout Africa, millions of homes and businesses are getting by without electricity. Millions more have electricity… But then they don’t… And then they do (or don’t) again – all in the same day.

Highlighting this problem, Afrobarometer’s new survey, published in March, found that only four in 10 Africans enjoy a reliable power supply. It’s a problem across the continent, from South Africa (where ‘load shedding’ has become a national punchline) to Ghana (where the Akan word ‘dumsor’ – or ‘on-off’ – has become part of everyday conversation).

Africans of all stripes are being forced to find their own energy solutions, with many believing the answers lie away from the centralised grid, in options such as solar systems, micro-grids and increasingly efficient generators.

Schneider Electric is among the leaders in off-grid power – harnessing clean, reliable solar energy through products such as their Conext SW inverter/charger. In October 2015, the company helped provide low-cost off-grid solar energy solutions for rural communities in six Nigerian states: Gombe, Anambra, Delta, Kaduna, Osun and Niger.

The systems are expected to supply power to about 200 clients in each of the communities, via a 2 km 230 VAC (volts of alternating current), 50 Hz mini-grid electricity distribution network. Once online, the project will offset an estimated 1 000 tons of CO2 annually.

‘We believe access to energy is a basic human right,’ says Walid Sheta, Schneider Electric country president for anglophone West Africa. ‘We want homes in Nigeria to have access to reliable, safe, efficient and sustainable energy.’

Schneider Electric is rolling out solar energy systems across the continent, and it’s doing so in a measured, strategic way – specifically aiming to succeed where other solar projects have failed. Solar power seems an obvious solution in Africa – after all, our deserts and plains have an abundance of sunshine – but in countries such as Nigeria, many solar energy initiatives have simply failed to deliver.

‘Access to energy is a basic human right. We want homes in Nigeria to have access to reliable, safe, efficient and sustainable energy’

A study by researchers at the Netherlands’ University of Twente, published last month in the journal Renewable Energy, found that most of the governments and agencies that plan solar projects lack awareness of how many people they want to reach, whether the location is suitable, and how that plant and the households it hopes to benefit would be connected to the grid.

‘So many projects fail because, when we talk about solar parks in Africa, most of the time people think this is just about finding an empty plot of land and implementing a project,’ wrote study author Eugene Ikejemba. ‘What motivated us to do the research was the fact that so many small businesses in Nigeria close up due to power problems. The introduction of parks that generate both solar and wind energy would be a robust and environmentally friendly way to provide electricity.’

When it comes to energy, environmental sustainability is becoming as important as cost, as Africa searches for power solutions that are both cheap and clean. In March, power generation giant Cummins began flooding the West African market with a line of state-of-the-art generators designed to reduce noise and cut fuel consumption by up to 20%.

‘Climate trends are now demanding environmental stewardship, and that all users of power employ tactics to reduce harmful emissions,’ says Nalen Alwar, Cummins Southern Africa projects sales manager.

‘Organisational success won’t be measured by financial performance alone. Environmental performance is likely to feature in the near future in terms of sustainability targets, such as carbon footprint reduction and acting responsibly. There is a need for environmental responsibility in the pursuit of increased power production, and Cummins have products to leverage both economic and environmental benefits,’ he says.

Alwar adds that Cummins’ newest diesel generator power plants are being designed with those requirements in mind. The old, loud, polluting generators that used to rattle and belch across Africa’s blacked-out suburbia and industria are now making way for far more efficient diesel units.

‘Compact designs have resulted in footprint reductions, and increases in power output have been achieved by increasing cylinder peak pressure, while also reducing the conventional number of cylinders required,’ says Alwar. ‘Ductile iron blocks with the highest structural strength are used to achieve multiple overhauls with minimal remanufacturing. Durable pistons can be forged from a single piece of steel, allowing reuse at the rebuild stage.

‘Premium materials are used for piston rings and hardened cylinder features, together with enhanced piston cooling, reduce piston ring temperatures and increase wear resistance and cylinder life.

‘This reduces total life-cycle costs. Diesel generated power is still likely to feature on its own or incorporated into hybrid solutions for many more years.’

‘Climate trends are now demanding environmental stewardship, and that all users of power employ tactics to reduce harmful emissions’

Smarter generators and off-grid solar plants are providing immediate solutions to Africa’s energy crisis. But as the continent’s governments and businesses look to the future, some are already finding that the real fix may lie in the actual structure of the buildings.

‘There’s a shift away from the brute-force approach to energy provision, which says, “Oh, I’ll just get a generator”,’ says Alison Groves, sustainability consultant at multi-disciplinary engineering consultancy WSP/Parsons Brinckerhoff Africa. ‘The idea now is for the building itself to be as self-reliant as possible.’

Groves uses the example of Nobelia, WSP/Parsons Brinckerhoff Africa’s 19-storey office tower project in Kigali, Rwanda.

Nobelia, which is still in its development phase, will be the first African building outside of South Africa to achieve a 6-star green building rating. It will achieve this in large part through efficient use of energy and innovative use of its environment.

‘Kigali is a lot like Johannesburg, in that they have a broad spread between their night- and day-time temperatures,’ she says.

‘The building has hollow core concrete slabs, and they pump cool night air through the building to cool those slabs. During the day, the thermal mass of the slabs releases energy into the space, so you have a cool environment generated by the actual structure of the building.’

Nobelia will have a mesh draped over its exterior, with plants and creepers growing on it to provide natural shading, and to wick moisture (and humidity) from the interior.

‘It’s a very organic-looking building, with twists and shifts in its space,’ says Groves, adding that Nobelia draws on a tradition of using thermal mass and materials to achieve energy-efficient comfort in buildings.

‘In the 1910s and 1920s, people built like this,’ she says. ‘You thought about the orientation of the building. You built for thermal mass. You built windows that had cross-draughts in the summer, and thick walls that would retard cooling in the winter.

‘If you’re doing that naturally, that’s one less bit of energy that you have to provide for your building.’

In Nobelia’s case, that’s a fairly sizeable bit. WSP/Parsons Brinckerhoff Africa’s studies found that Nobelia will be 88% more energy efficient than a notional, comparative building.

Groves believes this design-driven approach to energy-efficient buildings represents the future of Africa’s energy-saving efforts.

‘You can slam as much technology as you like into a building. That won’t make it more efficient,’ she says.

‘It’s like shopping on a sale: you’re saving money, but you’re still spending money.’