In South Africa, there are 8.5 million unemployed young people literally sitting around with nothing to do. That’s the equivalent of nearly the entire population of New York City being out of work. In South African terms, you could march 94 700 young adults into Soccer City Stadium in Johannesburg – and then replace them 89 times – before you found one person among them with a job.

‘Putting them to work is not just a national imperative, it’s also a way to reset our country’s economy in a post-Covid world,’ says Tashmia Ismail-Saville, CEO of the Youth Employment Service (YES). This is what the YES initiative is aiming to achieve.

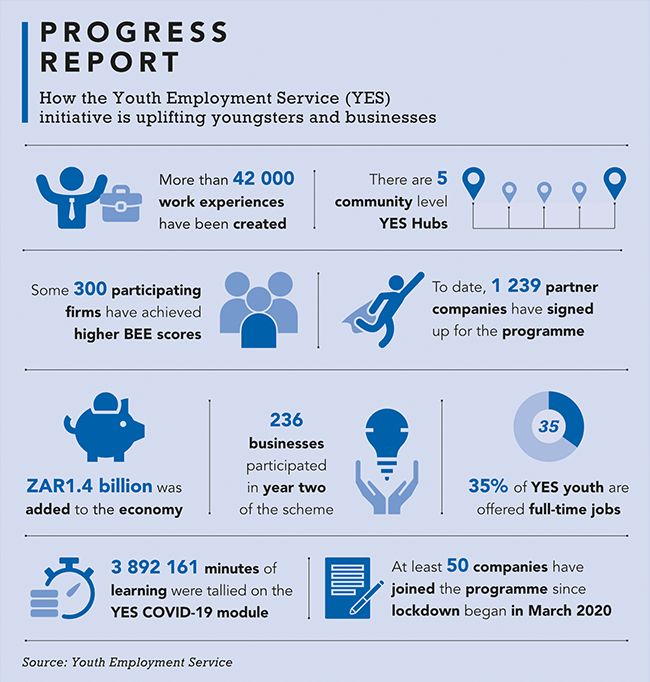

Since being launched by South Africa’s President Cyril Ramaphosa and becoming operational in January 2019, the business-led collaboration with government and organised labour has seen 1 239 companies commit to providing more than 42 100 paid work experiences for black, unemployed youth.

Although it does not receive any state funding, it’s one of the nation’s flagship youth partnerships – with another successful one being the Harambee Youth Employment Accelerator, which is partly funded by the government Jobs Fund. Harambee works with more than 500 employers (including Hollard, Woolworths, Nando’s, Direct Axis and Pick n Pay), which support a network of in excess of 700 000 work seekers, having ‘pathwayed’ young people into an estimated 160 000 jobs and work experiences.

Meanwhile, YES notes that its 12-month work-experience placements are leading to full-time employment for nearly a third of all participating youth. These are young South Africans who used to belong to the growing number of 15- to 34-year-olds classified as ‘not in employment, education or training’ (NEET) – a population group that is disengaged from the labour market while also not building on its skills base through education and training. The COVID-19 crisis caused this already massive group to increase from 40.4% to 43% (out of a total of 20.5 million youth) in the year leading up to the third quarter of 2020, according to Statistics South Africa’s Quarterly Labour Force Survey Q3/2020.

Young women are particularly hard hit by unemployment, with more than four in every 10 considered NEETs. The rate of female NEET youth rose by a staggering 20 percentage points in Q3/2020, compared to 3.1 percentage points for males. This disengagement is of great concern as it excludes those who should be shaping the future of the country through their youthful energy and innovative ideas from participating in the economy.

‘Many South Africans simply can’t get that first break to give them work experience. It becomes a vicious cycle: you can’t get a job without experience; you can’t get experience without a job,’ says Ismail-Saville. She further explains how YES helps to break this cycle by facilitating much-needed, paid work opportunities through corporate sponsorships.

It’s a mutually beneficial situation with significant benefits for the corporates too, as Ashleigh Hale, co-head of corporate at law firm Bowmans, points out. ‘Companies concerned about the impact of the pandemic on their B-BBEE level would do well to consider participation in the YES Initiative,’ she says. ‘Assuming certain qualification criteria and targets are met, a company may be able to claim enhanced B-BBEE recognition and improve its B-BBEE level by one to two B-BBEE levels.’ More than 300 companies have already levelled up their BEE scorecards this way. One is Isuzu SA, which placed 72 YES candidates in work experiences and achieved the highest possible BEE rating – a Level 1 score – in 2020.

‘Both large businesses and SMMEs have found YES to be a cost-effective, high-impact, broad-based transformation tool,’ says Ismail-Saville. ‘While our bigger corporate partners have certainly helped drive our numbers up, we’ve seen tremendous support from companies of all sizes and in all sectors, from finance to fast-moving consumer goods, with clients that include Nestlé, Investec, VW, Ford, Nedbank, Discovery, TIH, MTN, Shoprite, Woolworths, Oracle, IQ Business, Absa and AngloPlats, to name but a few.’

Hundreds of corporates have signed up for years two and three of the programme and continued their support even during the COVID-related lockdown. During this time, YES initiated the #Masks4All project, which enabled township entrepreneurs to manufacture and distribute cloth masks for large corporates such as Uber and Sun International, even exporting an order to Belgium.

A survey of the impact of COVID-19 on more than 3 000 young YES participants found that 80% of these youth were supporting more people financially with their YES salaries since the lockdown started, including family, friends and even neighbours. ‘The survey also highlighted the importance of technology and digital networks in the youth’s ability to access jobs,’ says Ismail-Saville. ‘All youth that YES places in 12-month work experiences are given smartphones, data and zero-rated training modules. The fact that 61% of surveyed youth are spending more on data and WiFi over other items at this time tells a powerful story of our youth’s need to stay connected, and the vital importance of technology and digital linkages in accessing and getting jobs in this economy.

‘4IR thinking and innovation is embedded in everything we do. Our entire operating model, including our innovative digital training, is based on international best practice from around the world. This digital connection allows us to act as ”a mentor in their pockets” and evaluate their progress through their work year.’ However, the problems that South Africa’s youth are facing are complex, entwined with other issues, deep-seated and often intergenerational, says Onyi Nwaneri, CEO of Afrika Tikkun Services, a social enterprise whose programme includes helping businesses interested in participating in YES. ‘It takes an intentional, holistic, sustainable and long-term approach to help children become rounded, economically active adults with relevant skills. We are advocating for the adoption of our Cradle to Career 360 model as the national blueprint for creating the country we want and need. This – developing young people from early childhood to post-matric – requires investments,’ she says.

In the career development and placement space, Nwaneri believes there needs to be a strong focus on personal mastery, self-leadership and personal development, to ensure youths have the necessary soft, or rather essential, skills and resilience to find their place in the workspace. She advocates for employers ‘to reduce their labour imports, start creating a local-talent pipeline and to employ/host young learners, interns and apprentices with a genuine intention of absorbing them into their workforce as their businesses expand and grow’. In the African context, this must also involve the informal sector, and the formalising and upskilling of existing job skills. According to Anthony Gewer, programme manager of social transformation at the National Business Initiative (NBI), ‘township youth in particular face significant barriers in accessing and sustaining employment opportunities. The evidence suggests that high transport costs disadvantage [in particular] low-income black youth living far from jobs. In the absence of capacity to generate entry-level training work experience in townships, the bulk of the youth workforce will be perpetually on the wrong side of these barriers to entry. Therefore, it is critical to support and develop township enterprises so as to grow economic activity and unlock employment and self-employment opportunities where young people live’.

To this end, the NBI is encouraging large corporates – through the Installation, Repair and Maintenance (IRM) initiative – to enable township SMEs in their supply and value chains to train and absorb youth. ‘Our goal is to grow market linkages between large corporates and township-based SMEs through their enterprise supplier development [ESD] strategies, as part of their local procurement and enterprise development investments,’ says Gewer. ‘Our goal is to make it as easy as possible for large corporates to develop and transact with township SMEs in communities surrounding their operations. In partnership with Tushiya Advisory Services, we are custom-building a model of engagement that assists large corporates to address both their local ESD and social-economic development objectives. The former by growing supply-chain relationships and incubating new township businesses, and the latter through the training of IRM students both in colleges and in the very SMEs they are supporting.’

A key focus lies on entry-level ‘IRM assistant’ jobs – where a young person can work under the supervision of a qualified artisan (such as plumbers, electricians, automotive mechanics and panelbeaters, with a special focus on ‘green’ artisanal skills, such as solar PV installers) and progress towards a trade qualification over time.

While it will take a concerted effort to break the cycle of chronic youth unemployment and create new career opportunities and pathways, it must be an urgent priority in the economic recovery plan. Ultimately, Africa can’t afford to ignore the millions of young people just waiting for their chance to participate in building a better future.