Twenty years ago, Chris van der Merwe, a schoolteacher from Durbanville, Cape Town, started his own school in a church hall after the Department of Education rejected his job application. And he’s never looked back. His model evolved into the ubiquitous Curro Independent Schools – from 28 pupils in its first year, it grew to become South Africa’s largest private-school business with more than 57 schools and around 51 300 pupils – and now its tertiary education offshoot, Stadio.

Stadio offers tertiary education, but not as we know it. It uses the language of business and aggressive roll-out plans, and its vision for South Africa is anything but modest. At its core is tertiary learning across a broad range of curricula (as well as curriculum development), the highest standard of excellence, and turning out successful, well-rounded graduates. Its offering looks just like a state institution – and must adhere to the same regulatory and accreditation requirements – but it’s privately owned and has to answer to shareholders.

Some of the brands under Stadio’s eclectic umbrella include Embury, AFDA and Milpark Business School (offering Africa’s first internationally accredited MBA). Its model includes greenfield developments as well as acquisitions, and in the mix is online, distance and campus learning. According to Julian Ribeiro, head of marketing, communication and sales at Stadio, the group aims to consolidate its existing brands towards a single private-education institution. The strategy involves both a registration process with the Department of Higher Education and Training (DHET) and the amalgamation of all existing qualifications into the one brand – Stadio Multiversity.

Look at its investor presentation, and you’ll see Stadio has big plans: among them to progress towards reaching 56 000 students by 2026; to find suitable land for expansion purposes; and to find a fitting and best-practice IT platform to service 100 000 students. ‘The time is right to do something great for South Africa,’ says Ribeiro. ‘We have big ambitions. Our aim is for our multiversity offering to be in line with the top universities in the world.’

Another example of best practice in the private space is Cranefield College. Designed specifically for students and working professionals, its academic qualifications are offered globally through online technology-enhanced distance learning, making it possible for students to attend interactive class-based and/or live online classes. ‘Cranefield is predominantly a post-graduate academic institution offering qualifications up to a PhD degree, with the average age of our students being 38 years,’ says Pieter Steyn, founder and principal. ‘All Cranefield’s academic qualifications, from the advanced certificate in project management to the PhD in commerce and administration, contextually focus on the Fourth Industrial Revolution economy,’ he adds. ‘This is characterised by the disruptive influence of digital-enabling technologies, and the transformation and change these have on leading, managing and governing today’s private and public organisations,’ he says.

Another alternative South African private model is TSIBA. A pioneer of the #feesmustfall movement, TSIBA Business School, registered as TSIBA Education in 2004, is another unique, private model in South Africa. TSIBA is a non-profit institution that awards scholarships to talented young people based on relative levels of affordability. TSIBA undergraduate students thus pay only what they can afford, removing financial barriers to tertiary education. In this way TSIBA accommodates students who would otherwise be unable to access higher education. With support from various financial and empowerment partners students do not ‘pay back’ their scholarships monetarily but are required to pay it forward – transferring knowledge, skills and resources they gain at TSIBA back into their communities.

TSIBA offers accredited certificates and degrees in business with an emphasis on leadership and entrepreneurship, subjects that the institution believes are critical to meeting the needs of the constantly changing workplace. Then there’s the ADvTECH Group, Africa’s largest private-education provider, which continues to increase its footprint on the continent. In recognition of the high demand for quality private education, the International Finance Corporation made a substantial investment in the group in 2016 in support of its expansion strategy.

Currently, ADvTECH owns nine tertiary brands, including Vega, Varsity College, Rosebank College and IIE MSA, across 30 campuses across South Africa and the rest of Africa. ADvTECH’s schools division comprises 10 brands with more than 100 schools across South Africa and Africa, including Gaborone International School in Botswana and Crawford International and Makini Schools in Nairobi, Kenya. The company also holds a 51% stake in Zambia’s University of Africa. ADvTECH’s tertiary division, its fastest-growing segment, offers 236 accredited qualifications ranging from higher certificates to master’s and caters to more than 36 100 students.

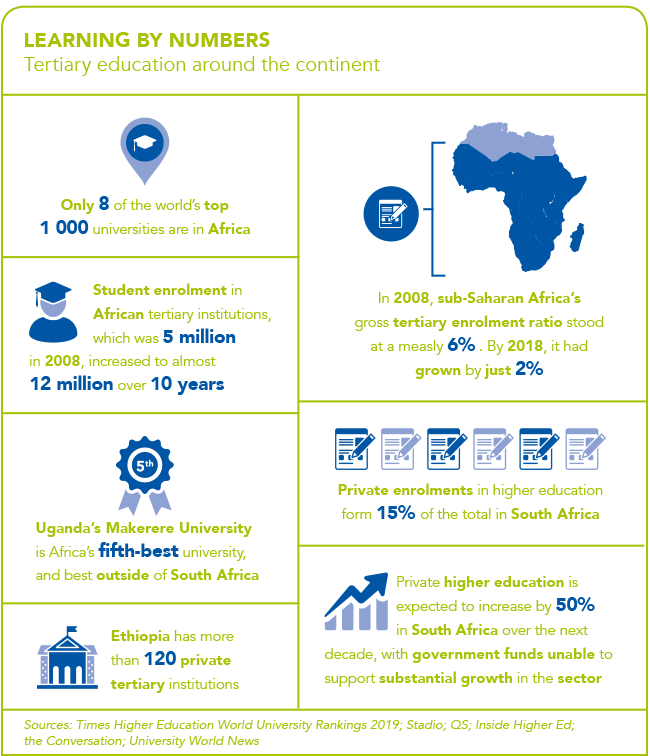

A recent article in South Africa’s Sunday Times sketched a worrying reality, however, of the state’s ability to meet demand. The University of Cape Town, for example, received applications for 32 000 hopeful candidates for the 2019 academic year, but could only take 4 200 first-year students; the University of KwaZulu-Natal had 91 000 applications for 8 770 first-year places, while Wits University had 70 349 first-year applications to fill just more than 5 000 spaces this year.

In its 12th Economic Update for South Africa, the World Bank suggests that for the country to grow sustainably – faster – it needs to address its skills gap that ‘perpetuates inequality and fuels policy uncertainty’. This would require enrolling more students in the post-school education and training (PSET) sector; raising graduation rates; and improving the relevance of skills specific to the needs of the labour market, according to the report.

Enter the critical role of private players. ‘We’re not there to compete with public universities but to provide an alternative offering to state institutions stretched to the hilt. We exist to widen access to higher education,’ says Ribeiro. Unemployment in South Africa stands at 27%, but graduate unemployment rates are under 5%, he points out. ‘That’s a very simple equation in terms of how to address the challenges in our country.’

Of course, it’s not all plain sailing for private companies. There are challenges to overcome, such as a viable fees model without the benefit of often hefty government subsidies from which public universities benefit; and forging a respectable reputation in this space, which takes time and a solid track record. Regulation is extensive.

Yet the pros are many, such as guaranteed quality education and inroads with the private sector, helping to facilitate employment. Private institutions don’t rely on government funding and are not subject to government pressure. They are often smaller than their public counterparts and are less bureaucratic by their very nature, so decisions can be made quickly.

The future is certainly looking bright for this sector in Africa, and it’s clear that private universities and colleges are uniquely poised to address the continent’s economic and development needs.