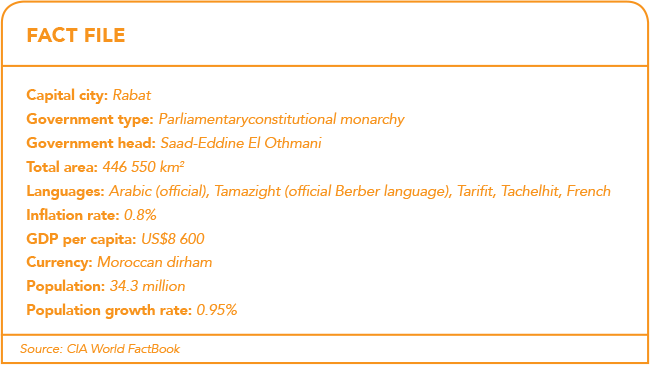

Several countries promote themselves as the gateway to Africa. Morocco, located only a few kilometres from Spain, across the 14 km Strait of Gibraltar, and with frontage on both the Mediterranean Sea and the Atlantic Ocean, has a better claim than most. With market-orientated industrial policies starting to show substantial success and a recent turn towards Africa in diplomacy and trade, the North African kingdom looks set to be a significant player in the continent’s future.

Morocco has traditionally been dependent on phosphate exports (it has among the world’s largest reserves), agricultural products and textiles. But under King Mohammed VI it has set out to diversify its economy with a particular ambition to make it less vulnerable to external shocks, especially oil price rises. The Industrial Acceleration Plan 2014–20 was intended to increase industrial output, as a percentage of GDP, from 14% to 23%. Dramatic expansion over the past decade in the automotive and aerospace industries suggests the plan is well on track.

The great success story of Morocco’s industrialisation drive has been the establishment of a sizeable export-orientated automotive sector. While cars have been made in Morocco since 1959, the industry surged in 2012, when French giant Renault, responding to government incentives, opened a large modern assembly plant in Tangier, tripling its production capacity. With access to the world economy through Africa’s biggest port, Tangier-Med, Renault’s investment rapidly established northern Morocco as an automotive manufacturing hub, especially for the European market. Renault has been followed by Peugeot-Citroën (currently in the process of ramping up production at its 100 000-vehicle plant north of Rabat) as well as Chinese electric vehicle manufacturer BDY, which announced investment plans in December 2017. In addition, it is suspected that Volkswagen has plans for a plant in the country.

Aerospace development has been even more impressive. In 2001 there were only 10 aerospace companies in the country, employing 300 people. But starting with an agreement by Royal Air Maroc to manufacture wire harnesses for the Boeing 737, the country has become a major aerospace manufacturing hub with 110 companies engaging 11 500 professionals, half of whom are women. An agreement with Boeing to build parts for the 787 Dreamliner is expected to bring 120 new supplier companies to the country. Morocco’s Minister of Industry, Moulay Hafid Elalamy, claimed last year that ‘100% of Boeing wiring is manufactured in Morocco’.

Other aeronautical companies with a manufacturing presence in Morocco are Bombardier, which built a US$200 million local factory near Casablanca in 2013; France’s Safan, which manufactures the Airbus; Dassault Aviation and EADS Aviation. According to Elalamy, exports exceeded US$1.2 billion in 2017 and the number of people employed in the sector expanded by 50% in the same year.

In 2017 Morocco built 376 826 automobiles, just more than 60% of the South African production total of 601 178. The two countries produce about 90% of the vehicles manufactured in Africa and may end up competing head to head for the African market (only 1.5 million vehicles in 2015, but this is expected to grow). At present, the rivalry between Morocco and South Africa exists mostly in their potential. However, Morocco is laying the groundwork for future African relationships.

The nation joined the AU in January 2017 after withdrawing from its predecessor, the Organisation of African Unity, in 1984. That rift occurred over Morocco’s occupation of the former Spanish Sahara in 1975, when the former colonial power exited shortly before the death of long-term Spanish dictator, general Francisco Franco. The subsequent civil war lasted until 1991 and some AU members – including South Africa – regard the issue as unresolved.

Morocco’s African pivot follows 30 years when the country focused mostly on its relationship with Europe and the United States. The US is a close military ally and holds annual joint military manoeuvres – known as Exercise African Lion – with the Moroccan Royal Armed Forces. However, after re-admission to the AU, Mohammed VI began an intensive series of visits to five sub-Saharan nations over a two-month period, resulting in the signing of in excess of 50 bilateral agreements.

There has been an increase in Morocco’s direct foreign investment in sub-Saharan Africa, which now accounts for 85% of the kingdom’s outward capital flows (up from 66% in 2008–13). Traditionally, Morocco invested in francophone and West Africa, where it dominates the banking industry, but is now looking further afield. There has been a recent US$3.7 billion Moroccan investment in a fertiliser plant in Ethiopia, another project in Rwanda and a fertiliser supply agreement with Guinea. Investments in the cement industry have gone into Côte d’Ivoire and Nigeria. Moroccan pharmaceuticals firms have invested in manufacturing facilities in Rwanda and Côte d’Ivoire.

However, Morocco’s trade with sub-Saharan Africa represents only 3% of the country’s international business, and trade with the EU remains its mainstay. The turn towards Africa should thus be seen as an indication of a willingness to focus more on the continent and perhaps as a harbinger of things to come. Some have argued, however, that the Saharan desert presents a big obstacle to physical trade with the rest of the continent. Nevertheless, Morocco’s African ambitions are illustrated by the fact that it has applied to join the regional trade bloc to its immediate south, the Economic Community of West African States.

It is significant that Mohammed VI has spearheaded Morocco’s engagement with Africa, for included in the country’s constitution reserved for the monarch are ‘strategic political choices’. Although Morocco has a hybrid constitution with an elected Parliament operating alongside royal authority, real power is generally regarded as vesting with the court. This is the so-called deep state where the most important decisions are made. Morocco was one of the countries along Africa’s Mediterranean littoral least affected by the Arab Spring of 2011.

Of its neighbours, only Algeria escaped a regime change (although it was far more heavily affected by unrest). Morocco’s response was a number of symbolic reforms – such as removing a constitutional clause declaring the king to be sacred – which did not affect the country’s basic power structure. Nevertheless, Mohammed VI is widely seen as a reformer who wants to move the country in a more liberal democratic direction.

Morocco’s surge has come on the back of political stability and a conservative fiscal stance (inflation has not risen significantly above northern European levels for the past decade), as well as a massive infrastructure development programme. Between 2010 and 2015, the government spent US$15 billion on basic infrastructure, mostly on road, rail and harbours.

New high-speed railways now link Tangier with Casablanca, and Casablanca with Marrakech. Four harbours are either under construction or in planning, and a structure that allows competition between ports has been initiated. Major road upgrades linking Tangier to Agadir, and El Jadida to Casablanca and Oujda have been completed. Morocco published the country’s first legislation enabling public-private partnerships (PPPs) in 2015; the opening up of this space is expected to leverage more foreign investment.

The PPP legislation is part of a more widespread pattern of investment climate reform. Morocco is the best-ranked country in North Africa in terms of the World Bank’s Doing Business indicators and ranked third in Africa as a whole, after Mauritius and Rwanda. Recently, Doing Business placed Morocco 60th in the world (out of 190 countries), nine up from 2018 and a striking improvement from 128 in 2010.

Morocco has spread its wings dramatically over the past decade. Its premium location, linking Europe and Africa, is a massive advantage. But this would be meaningless in the absence of market-friendly pro-business policies. These are now in place.