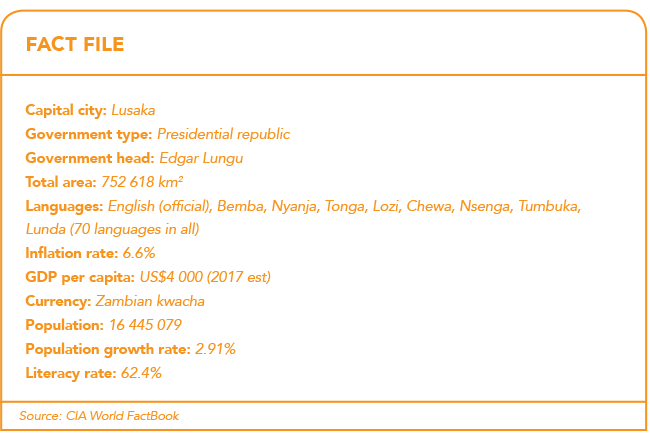

Zambia has been mining copper since the 1920s and the metal remains central to its economy. However, the current government, under President Edgar Lungu, has implemented an infrastructure-based development plan to take Zambia beyond dependency on a single commodity and towards developed-country status by 2030.

While the programme has already delivered some impressive results, Zambia is heavily indebted – government spending has been cut over the past two years but the country still faces a seemingly intractable debt problem. The question is if the infrastructure development will raise growth enough to bridge the gap. Among Zambia’s achievements since the Patriotic Front government came to power in 2011 has been self-sufficiency in electricity.

For decades Zambia has been dependent on hydroelectricity, from the approximately 1 000 MW power station at Lake Kariba and the 900 MW Upper Kafue Gorge facility. But hydropower is regularly affected by inconsistent rainfall, which used to mean unreliable supply and periodic rolling blackouts. So it was a familiar scenario in February when the state-owned power utility, ZESCO, announced that drought conditions necessitated cutting capacity at Kariba to 500 MW. But for the first time ever this did not mean the lights would go out; Zambia has been self-sufficient in energy supply since the first quarter of 2018.

The 120 MW power generator at Itezhi-Tezhi in the south-west part of the country came on-stream in 2016, making use of a reservoir completed in 1977. It is due to be followed by the much bigger Kafue Gorge Lower facility (750 MW), built and financed by Chinese interests, and expected to come on-stream later this year. But the big shift has been developments away from almost total dependency on hydropower. The 300 MW Maamba thermal coal plant was finished in 2017. In addition, a 54 MW solar plant went active in March, with the construction of a smaller 34 MW plant expected to be complete this year – both near the capital, Lusaka.

These new power stations are only the first phase in Zambia’s pattern of plant construction and diversification. US$1.15 million was provided by the US Trade and Development Agency for a feasibility study in the wind-power sector. Plans for solar PV developments are also big news with a 100 MW tender launched in 2018. Bids for another 300 MW of solar power throughout the country are expected. Another 300 MW coal-powered thermal station, located in the south and built by EMCO, is expected to come on-stream this year.

The country’s democratic system is robust – having seen national leadership rotate between three different parties since 1990. The governing Patriotic Front party talks socialism but has been more inclined than any of its predecessors to facilitate private investment. Several of the big energy projects are effectively public-private partnerships. Private investment in power generation has become far more attractive since the government took the politically unpopular step of abandoning a flat, subsidised electricity tariff and moving towards commercial cost-reflective rates. This raised electricity prices by 75% in 2017.

Recognition of a major role for the private sector in a country – which pioneered statist African socialism (and nationalised the copper industry in 1970) – is an important shift. ‘The participation of the private sector in our economy cannot be overemphasised. For our economy to become resilient, the role of the private sector is inevitable,’ says Lungu, whose government ‘has consequently created an enabling environment for the private sector to take part in spurring economic development’.

Data suggests that these reforms are rolling forward. Zambia currently ranks sixth in sub-Saharan Africa in the World Bank’s annual Doing Business indicators. In fact, in two of the World Bank’s categories – getting credit (rank 3 out of 190 countries) and administrative ease of paying taxes (rank 17), it is among the global leaders. In 2017 the World Bank recognised Zambia as one of the top 10 reformers globally. However, business climate reforms have been somewhat patchy, and there are other areas that need attention. For example, Zambia is only 128th best at connecting its citizens and businesses to electricity. Meeting the administrative requirements takes 117 days and connections – which cost 2 329% of average income – are designed with big companies in mind.

There is still a huge backlog in electricity connection for ordinary citizens. Only 27% of the urban population and 3% of rural dwellers have access to the electrical grid. This does, however, mean that there are business opportunities in the off-grid space and it is reported that 500 000 rural Zambians have accessed solar-driven mini-grids in the past 18 months.

Other elements of the infrastructure surge are thousands of kilometres of roads built or resurfaced, mostly with Chinese involvement. The road network is expanding – and with that, associated housing, schools, health facilities and office spaces across the country. Still under construction, the Kazungula bridge will link Zambia to Botswana across the Zambezi river and, together with new road infrastructure, will form an important part of a development corridor. In addition, Zambian Airways intend to re-launch this year after suspending operations in 1994.

The biggest companies in the country remain the copper miners. It is critical that Zambia, in its enthusiasm for diversifying development, does not neglect the sector, which still provides the basis for its development prospects. Copper accounts for two-thirds of Zambia’s exports by value and the mining industry absorbs 57% of all electricity generated. Zambia is the second biggest copper producer in Africa, slightly behind the DRC, with which it shares the Central Africa Copper Belt. But the country hopes to increase production from 2017’s 755 000 tons to 1.5 million tons. This means keeping the copper miners sweet while also looking to diversify the mining industry.

There were protests from at least two of the four big copper mining companies (First Quantum and Glencore) when electricity prices were hiked in 2017. The miners seem to have accepted the higher price in exchange for greater security of supply. There are still, however, mutterings about changes to the regulatory framework for mining.

Zambia has seen many mining tax changes in the past 16 years. In late 2018, the government increased royalties by 1.5% across the board. Although the industry protested, government was able to point out that the tax hike is indexed against fluctuations in the global copper price. It will be curbed should the metal’s price fall, but an additional 10% will be charged if copper climbs above US$7 500/ton (it’s currently around US$6 500). However, Zambia is hoping to move beyond copper and has invested in a countrywide geological mapping project. A further 0.9% of the country was added to the areas surveyed in 2018, bringing the total covered to 61%.

Private-sector exploration and greenfield development has been negligible for the past seven years and some observers – including auditors PwC Zambia – are unsure whether the geological survey counterbalances uncertainty concerning the mining tax regime. A further headwind listed by PwC Zambia is the slight decline in copper prices ‘as a result of weaker demand from China on account of trade tensions with the US’. Quite how this factor plays out remains to be seen.

This huge infrastructure-based surge has come at a cost and concerns have been expressed that the country may have reached its debt limit. PwC Zambia, for instance, says that with external debt of US$9.4 billion (up from under US$1 billion in 2006 after a World Bank-managed debt-forgiveness programme), it is time for austerity. The auditing firm notes that the government has responded appropriately in the 2019/20 budget, promising only to finance infrastructure projects that are more than 80% complete.

Zambia is hoping that the new infrastructure and its business-friendly regulatory framework is going to soon deliver the dividends it needs to deal with its debt. Growth has been reasonably strong at around the 4% mark for 2017 and 2018 but probably needs to return to the 7% of 2010 to 2014 to be sustainable.