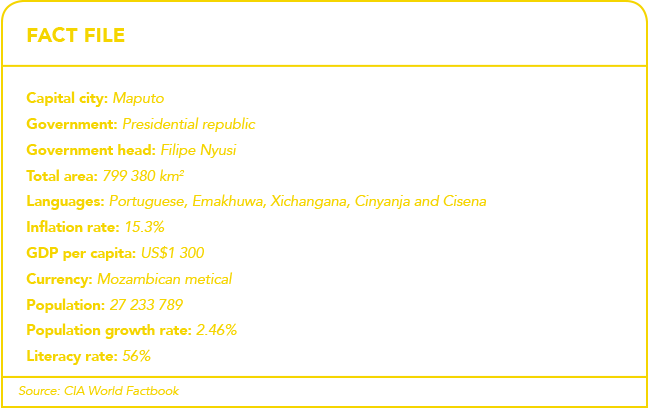

The discovery of huge liquefied natural gas (LNG) deposits off the Mozambique coast is exciting; so too is the boom in mining and an increase in the country’s tourism. However, in terms of investment, the gas find is the critical next step or ‘game changer’. The Portuguese-speaking, almost 30 million-strong Southern African nation is still one of the world’s poorest countries, ranking 178 out of 184 with an annual per capita income of just under US$1 300 based on purchasing power parity. Properly managed, the gas boom, combined with other areas that have started to thrive recently, offers the country the chance to develop out of its poverty trap.

Quite what a game changer the development of Mozambique’s gas industry is, is illustrated by comparing the size of the investment of the oil and gas majors with the country’s GDP, which was at US$14.46 billion in 2018. The big gas monetisation projects in Cabo Delgado are estimated to amount to more than US$100 billion over the next two decades. Mozambique LNG, a consortium led by Total, made its US$20 billion commitment in mid-2019. The financial investment decision (FID) for the other mega-project, Rovuma LNG (ExxonMobil, CNODC and Eni), which will cost an estimated US$30 billion, is expected this year. The US$4.7 billion Coral South floating LNG (FLNG) vessel was quicker off the mark, with Italian firm Eni announcing its FID in 2017.

The Coral South FLNG unit is a 220 000 ton vessel, currently under construction in Asia. On completion it will be positioned 80 km off Palma Bay in Cabo Delgado. Production is expected to start in 2022, ramping up over time to 3.4 million tons a year.

Mozambique has confirmed gas finds of some 150 trillion cubic feet. These could make it vie with Russia to be the world’s fourth-largest LNG producer – after the US, Qatar and Australia – by the end of the 2020s. South Africa’s Standard Bank estimates that foreign direct investment into the industry could reach US$128 billion by 2025.

Mozambique suffers from a cycle of drought, cyclones and flooding, which has for centuries made life precarious. With the country divided into distinct northern and southern regions by the Zambezi river, and trade linkages running inland from the coast, successive administrations have struggled to integrate it as a coherent entity. There has been much difficulty linking railway networks throughout the country (often due to conflict) and the coastal road has been periodically broken by civil war and cyclones.

The north-south divide was at its most intense during the Mozambican civil war (1977 to 1992). The north was largely controlled by the rebel Renamo movement while the sole official ruling party, Frelimo, held much of the south. Huge parts of the country became effective no-go areas, riddled with landmines, the last of which was cleared only in 2015. The Gorongosa national park, which should have been the jewel in the crown of conservation tourism in Mozambique, was a Renamo base and staging area. The war devastated the economy, already weakened by Frelimo’s doctrinaire Marxist economic policies.

The Rome General Peace Accord of 1992 saw the introduction of multi-party democracy and Washington consensus-style economic policies. The most recent election, in October 2019, saw the re-election of Frelimo with incumbent president Filipe Nyusi winning an overwhelming 73% of the vote. But the rather fragile nature of Mozambican politics is demonstrated that for the election to go ahead, a third Frelimo-Renamo peace accord, was needed. The World Bank warns that implementation of the peace accord, which mandates the integration of the remaining Renamo fighters into the national army, is likely to be ‘rather tumultuous’. In the meantime, the bank says, the government is grappling with ‘a low-level so-called Islamic insurgency in parts of gas-rich Cabo Delgado’.

The development path followed by Mozambique has revolved around mega-projects. The first was the Mozal aluminium smelter in Maputo, which began operating in 1998. This was important primarily in establishing the country’s credentials as a viable investment destination. According to the IMF, ‘the Mozal smelter demonstrated that large-scale investments could be successful in the country’s post-conflict environment’. According to 2018 data, aluminium accounts for 25.1% of Mozambique’s export earnings (US$1.3 billion) despite the fact that the country mines minimal amounts of bauxite.

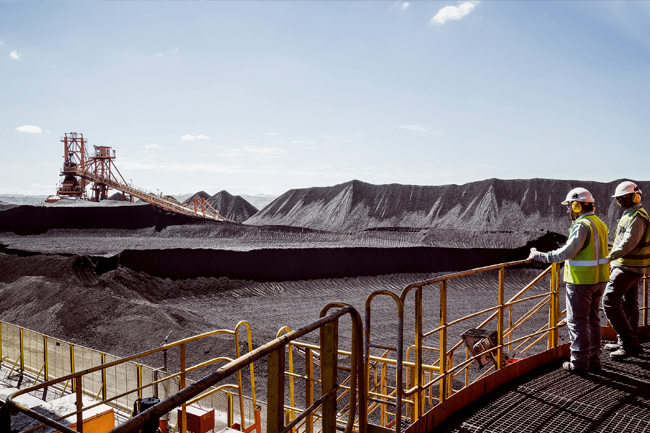

Subsequent development has mostly been about mega-projects, such as the three big gas monetisation projects and the coal project in the Tete province. Owned by Brazilian major Vale, the mine is situated on the world’s ninth-largest coal deposit, a 25.6 billion ton resource at Moatize. Bringing it into commercial operation has required the construction of a 912 km railway line linking it to a new coal terminal at the port of Nacala. The first coal was shipped in 2011 and tonnages have increased every year since then.

The Mozambican government believes the country could be exporting 15% of the world’s coking coal by 2025. Another area of recent development is heavy sands mining, which produces a number of minerals, notably titanium (which makes the white pigment in paints). Four big projects have been developed in the country – two by Chinese firms – with more in the pipeline. Heavy sands mining is often classified with the mega-projects but this is misleading as they require far less initial investment (around US$200 million to US$400 million). They also tend to employ more people, nearly 1 400 at Kenmare Resources’ Moma mine, one of the older heavy sands projects, which started in 2007.

Heavy sands mining can be very destructive to both the environment and local communities. A tailings dam at Moma mine failed in 2010, destroying a local village and leaving a child missing. More recently, the Africa Great Wall’s Nagonha project in Nampula has been criticised for the environmental damage done. Two large lagoons that used to control local flooding, and a large wetland area, have since been submerged by mine sand.

Heavy sands mining – because it ‘processes’ coastal sand dunes – requires considerable ecological sensitivity. It is unclear if environmental regulations are always adequately implemented in Mozambique.

There is a well-known drawback to mega-project-based development: they are capital-intensive, employ relatively few people and the returns generated tend to accrue to a small minority. For instance, while the Mozal smelter’s contribution to the GDP is 5%, it uses only 0.02% of the country’s labour force. The big problem is that Mozambique is an extremely unequal country, with 82.49% of the population living in poverty, defined as less than US$2 per day. The fact is that mega-projects are not good at spreading wealth among the population. But as the country develops, sectors that do this better are emerging. Primary among these is tourism.

Under the Portuguese colonial regime prior to formal independence in 1975, Mozambique had built a thriving tourism trade based on South Africans who wished to spend time away from the Calvinist restriction of apartheid rule. Maputo, then called Lourenço Marques, was an especially popular destination. The industry was effectively brought to an end by the civil war but, since conflict largely ended in 1992, it has slowly revived. Recovery began in high-end enclaves such as the hotels of the islands of the Bazaruto Archipelago, in the 1990s, which were directly accessible by air; Bazaruto Island itself is the site of a five-star hotel opened in late-2018. The less upmarket Inhambane peninsula attracted middle-class South African tourists. Maputo itself recovered rapidly, led by the Polana Serena hotel, which has been operating since 1922. Maputo has since become the location of choice for international hotel groups such as Radisson, Marriott and AccorHotels.

In 2018 the World Travel and Tourism Council rated Mozambique one of the fastest-growing African leisure destinations. In 2018, 2.8 million tourists visited, up from 1.6 million in 2016. The promise of the tourism sector as a development vector is recognised by the government, which plans to use about EUR190 million in mainly private sector funds to transform Maputo into a tourist centre.

It is hoped that this funding will kick-start the development of some of the hidden infrastructure required to localise the industry – boosting local travel agencies for instance.

Mozambique’s trade profile is typical of a less developed country. It is a supplier of raw materials (coal, agriculture, fisheries) into the global economy and an importer of manufactured goods. In 2018, Mozambique’s single-biggest export earner was coal to India, earning about 27% of the country’s foreign exchange. But there are international institutional arrangements in place that will facilitate future development.

Mozambique is a member of SADC, which makes trade with its giant neighbour, South Africa (its biggest trading partner), easier. It can also be expected to reap the benefits of the lower barriers to trade implicit in the African Continental Free Trade Agreement, currently in negotiation. There are also signs that the outside world prefers to deal with Mozambique together with the Southern African Customs Union (SACU), a block of

five member states (South Africa, Lesotho, Namibia, Botswana and Eswatini) whose relationship goes back to 1910.

In 2019, the UK negotiated an economic partnership agreement with Mozambique on the same terms as the five SACU members, a grouping referred to by the UK government as ‘SACU+M’. The agreement is intended to continue enjoying preferential trading terms after Brexit. It makes sense for the UK to deal with the six Southern African countries as a group, as they are all members of the Commonwealth. Mozambique was admitted to the club in 1995.

Mozambique has the prospect of a bright future. But as the World Bank points out, it needs to maintain macro-economic stability – avoiding the dreaded ‘resource curse’ – and improve the transparency of its governance. Beyond that, it needs to diversify away from the current focus on capital-intensive mega-projects ‘toward a more diverse and competitive economy’. Critical building blocks are in place. Now is the time for wise choices.