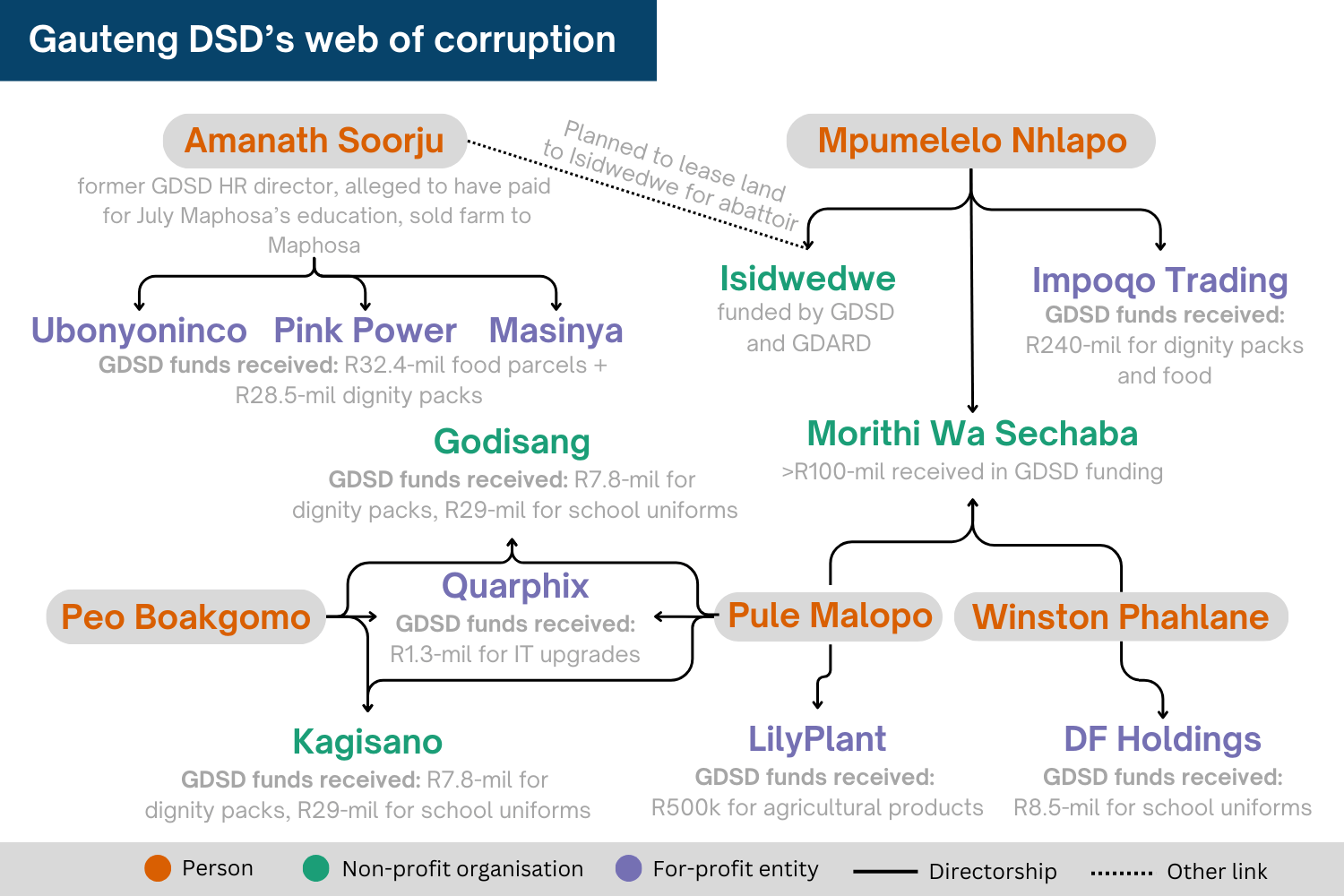

Half a billion rand was funneled via non-profit organisations to private companies without tender processes between 2016 and 2018. Graphic: Lisa Nelson.

By Daniel Steyn and Raymond Joseph

- July Maphosa, a former senior official at the Gauteng Department of Social Development, channeled hundreds of millions of rand to non-profit organisations and private companies without tender processes.

- Many of the entities were closely linked and shared directors. Maphosa is alleged to have personally benefited from the contracts.

- A forensic audit was conducted in 2019 but it was buried by the department’s leadership. None of the implicated officials, including Maphosa, have been held to account.

Forensic audits on fraud and corruption at the Gauteng Department of Social Development have identified a senior official responsible for irregularly paying at least R500-million between 2016 and 2018 to for-profit companies via non-profit organisations.

GroundUp reported on Wednesday how the department buried the forensic reports, which were conducted by law firm Bowmans and auditing firm BDO.

Dozens of officials are implicated by the reports.

The person at the centre of the scandal is July Maphosa, the department’s former director for the sustainable livelihoods programme. This massive portfolio, with a budget of about R250-million a year, included projects to provide school uniforms, dignity packs and food parcels to poor people.

Maphosa resigned from the department in 2018 for “personal reasons”, shortly after a fraud complaint was laid against him by convicted car hijacker Japhta Mookang, who was involved with several organisations that received funds from the department. Maphosa was subsequently charged, but the charges were later withdrawn and no further investigation into Maphosa has taken place.

Letters sent to non-profit organisations by Maphosa, which the investigators analysed, show that the organisations were instructed to appoint specific companies to provide goods and services.

The reports describe this as an “elaborate scheme to circumvent the normal supply-chain management processes, [and] to enable Mr Maphosa, and other officials, to appoint suppliers directly, without having to be subjected to the scrutiny of a rigorous supply-chain management process”.

Maphosa did not respond to GroundUp’s questions.

Contracts for pals

Ubonyoninco, Pink Power Trading and Masinya Trading are all owned by Amanath Soorju. He was once the human resources director in the Department of Social Development, but left the department about a decade before the events described here.

According to the forensic audit report, Soorju’s companies were allocated a total of R28.5-million for dignity pack supplies and R32.4-million for food. The three companies submitted quotations, which were assessed by Maphosa and his colleagues, and all three were allocated funds via non-profit organisations.

Speaking to GroundUp, Soorju described Maphosa as a “friend” but denied there was a conflict of interest. He said he did not know that the non-profit organisations he supplied were instructed by Maphosa to contract his companies. He said that he dealt directly with the organisations, not with the department.

The investigators also found invoices for Maphosa’s education at Cranefield College, addressed to Soorju. Soorju denied that he paid for Maphosa’s studies and said it is possible his name was still on the invoicing system from when he was HR director at the department and in charge of the bursary programme.

GroundUp has also found that Soorju, in 2015, sold a property to Maphosa in Magaliesberg, down the road from another property which Soorju was considering renting to Isidwedwe Clothing Co-operative to start an abattoir.

That cooperative also received funds from both the Gauteng Department of Social Development and the Gauteng Department of Agriculture. One of the directors of the cooperative, which Soorju denies being involved in, is Mpumelelo Nhlapo.

Nhlapo was also a director of both Morithi Wa Sechaba, a non-profit organisation that received tens of millions from the department for a range of programmes, and Impoqo Trading, a private company that was paid more than R240-million for dignity packs and food by various department-funded organisations on instruction by Maphosa.

The Bowmans report reveals allegations by a whistleblower that Nhlapo had paid for Maphosa’s trip to Dubai. Although this could not be fully proven, the investigators found in Maphosa’s emails an invitation letter from a Dubai-based company, addressed to Maphosa and Nhlapo, as well as full-fare business class tickets for Nhlapo, which Maphosa had emailed to himself.

Nhlapo declined GroundUp’s request for comment.

Hundreds of millions of rands in public money flowed via non-profit organisations to private entities, many of them with links to department officials or shared directors. Graphic: Daniel Steyn.

Morithi Wa Sechaba, Godisang and Kagisano

Morithi Wa Sechaba, the organisation of which Nhlapo was a director, had various projects funded by the department. It received a total of R109-million between 2017 and 2018, including R17.6-million for dignity packs and R8.4-million for school uniforms. The organisation also received an additional R1.2-million for upgrading a Disaster Management mobile app, but the investigators couldn’t determine whether the app was ever created or used.

Investigators said they could not properly analyse the organisation’s bank accounts to determine which suppliers had been paid, because Morithi Wa Sechaba, which has stopped operating, could not be reached by the investigators.

A chartered accountant contracted to be part of the adjudication committee for co-ops for the school uniform programme, was paid R101,000 by Morithi Wa Sechaba on instruction from the department. The accountant was irregularly appointed and should not have been paid by the non-profit, the audit found.

Another director of Morithi Wa Sechaba, Winston Phahlane, issued invoices on behalf of DF Holdings, which was paid a total of R8.5-million for the school uniforms project. Phahlane did not respond to GroundUp’s questions.

A third director of Morithi Wa Sechaba, Pule Malopo, was also the director of Kagisano, a non-profit organisation that was paid R30.6-million to project-manage the school uniforms project. Some of the funds were paid before a contract was signed. The investigators said the process to award the contract to Kagisano appeared “rushed” and also that Kagisano was given an unfair advantage.

Some of Kagisano’s funds were also used for the department’s food programme, but Kagisano could not provide supporting evidence for this expenditure to the investigators. Of this, R3-million was paid to an unidentified bank account. And, according to the reports, Kagisano also loaned R1.3-million to unknown recipients.

Malopo is also the director of LilyPlant, a for-profit company which received R500,000 from Kagisano for “JoJo tanks, seeds, fertilizer and aluminium fencing”.

Another director of Kagisano is Peo Boakgomo, who is also the director of Godisang Development, which received R7.8-million for dignity packs and R29-million for school uniforms. Godisang submitted its original application for funding two months after the deadline, yet was still contracted.

Malopo and Boakgomo own several businesses together. GroundUp reported in September how they went into business with convicted hijacker Japtha Mookang, who was also a board member of Morithi Wa Sechaba and the owner of an agricultural co-operative that supplied vegetables to food banks.

According to the forensic reports, R1.3-million was paid by Kagisano to Quarphix, a company owned by Boakgomo and Malopo, for computer system upgrades.

Despite the report recommending that Godisang be blacklisted, it received a further R54-million between 2021 and 2023 for training programmes from the department, according to leaked departmental funding records.

Other companies also benefited from non-profit organisations linked to them. Phokeng School Clothes and Stationery, a closed corporation, received R9-million between 2016 and 2019 to supply goods for dignity packs. The managing director of Phokeng, Victor Mazibuko, is the director of several companies and co-operatives that also received funding from the department.

We could not reach Mazibuko for comment.

Another organisation, Philani HIV/AIDS Programme, received R3.6-million for the school uniforms programme which was paid directly to National Matters, a company owned by the organisation’s director, Simao Mondlane. Delivery notes for school uniforms delivered to Philani were issued by Anibal Production and Marketing, another company owned by Mondlane.

Phyllis Malope, a director of Philani, told GroundUp that “we never questioned [the department’s] procurement processes. I assumed that they work within the premise of their policies.”

Malope said the money was used for school uniforms and was paid via the National Matters bank account to avoid bank charges for the non-profit organisation. Mondlane’s company Anibal Production and Marketing was a music recording company that never received any funds from the school uniform project, Malope said.

Unspent funds not returned

Katlego, a non-profit, received R8-million but underspent its budget by R3-million, with no indication of how the remaining budget was spent.

Tshepo Themba Development Centre had R1-million of its R32-million allocation left at the end of 2017/18, but there is no evidence that it was paid back to the department. It paid R1.4-million to DF Holdings, the company owned by Phahlane.

Kumaka, a non-profit, received R10.5-million for delivering dignity packs to school, but the investigators could not verify the expense because funds were not kept in a separate bank account.

A non-profit called Gender Equality Network was paid R6-million in the last few weeks of the 2016/17 financial year. The auditors questioned why this large payment was pushed through at the end of the year. The money was originally allocated for “ECD renovations”, but some of the funds were reassigned for dignity packs on instruction from department officials, contrary to the organisation’s contract and approved budget.

Food banks

About R270-million was spent on the department’s nutrition programme between 2016 and 2018. This involved five non-profit organisations that were appointed as “food banks” to supply and distribute food parcels to beneficiaries. But the funds ultimately flowed to private companies picked by the department.

Some of the companies that supplied food to food banks include Soorju’s companies, Nhlapo’s Impoqo, and Mookang’s Khayalethu Agricultural and Multi-Purpose Co-Operative.

The Gauteng Department of Social Development did not respond to GroundUp’s questions. It has been ignoring our queries since July.

GroundUp reported that the Hawks are only now investigating the findings, five years after the reports were finalised.

See also: Gauteng government’s buried corruption investigation