Theophilus Acheampong, University of Aberdeen

Ghana is struggling with managing its debt, 20-year high inflation, a weak currency, and rising inequality.

For example, inflation rose to 33.9% in August 2022 from 9.7% a year earlier, while the cedi has depreciated by 41% year-to-date against the US dollar. These vulnerabilities have been worsened by the aftershocks of the ongoing Russia–Ukraine war and the COVID-19 pandemic.

These challenges have forced Ghana’s government to approach the International Monetary Fund (IMF) for an economic support package. Part of the engagement will involve a new assessment of the sustainability of the country’s debt.

Debt sustainability analysis classifies countries into four bands: low risk, moderate risk, high risk, and in debt distress. This is based on certain thresholds for key public debt indicators. Ghana’s last analysis, conducted in mid-2021, classified the country as being at high risk of external debt distress and overall debt distress. The assessment was carried out jointly by the IMF and the World Bank.

If the new assessment concludes Ghana’s debt levels aren’t sustainable, the country will have to take steps to restructure its debt to qualify for IMF assistance. The Fund states that it won’t lend to countries that have unsustainable debts unless the member takes steps to restore debt sustainability, which can include debt restructuring.

Recently, Zambia had to negotiate with all its external lenders, including bilateral and commercial creditors, as a pre-condition for accessing IMF funding. The process lasted almost two years.

Ghana needs to address its current crisis by tackling two issues.

Firstly, the restructuring of its debt. Here a good option would be to restructure its external debt as well as some limited domestic debt restructuring.

And secondly, it needs urgently to take six steps on the domestic front to get its financial house in order. This includes putting an end to profligacy in government spending and ensuring it lives within its means.

Ghana’s public debt dynamics

A country’s debt dynamics includes both external and domestic debt, and debt accruing to state-owned enterprises and its maturity structure. All need to be considered when considering any debt restructuring.

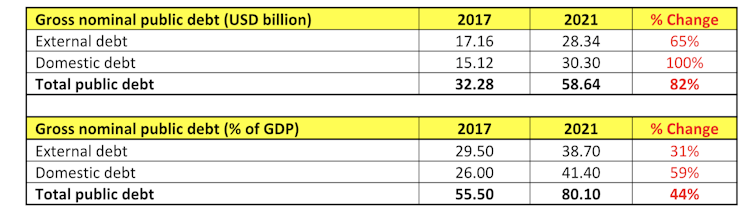

Ghana’s total public debt as of June 2022 was US$54.4 billion (GHS393 billion or 78.3% of GDP) from US$32.3 billion (GHS143 billion or 55.5% of GDP) in 2017, according to central bank and finance ministry data.

Of this, external debt was US$28.1 billion (GHS203.4 billion or 40.5% of GDP), while domestic debt issued in cedis was US$26.3 billion (GHS190 billion or 37.8% of GDP).

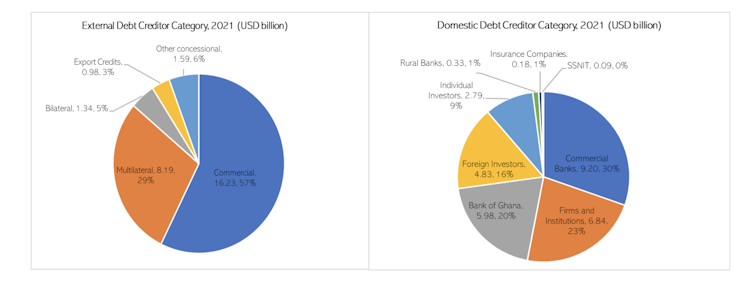

Regarding external debt, the portfolio includes debt owed to multilaterals such as the IMF and World Bank, bilaterals, commercial loans such as Eurobonds, and other export credits. The external debt also comprises of fixed (86.5%), variable (13.1%) rate and some interest-free (0.4%) debt. As of 2021, about 72% of the external debt was also dollar-denominated.

In 2021, the government spent US$2.2 billion in total external debt service, including principal repayments, interest payments and charges.

Of the domestic debt, Ghana’s government sourced as much as 85% of its domestic debt in 2021 via the market. This included financial securities and instruments traded on the secondary market. This means that Ghanaian banks, individuals and institutional investors, such as pension funds, buy and sell government securities such as treasury bills and other fixed deposits.

In 2021, Ghana’s banking sector cumulatively held 50% of the total domestic debt stock comprising commercial banks (30%) and the Bank of Ghana (20%). The non-bank sector comprised firms and institutions (22.6%), individual investors (9.2%), rural banks (1.1%), insurance companies (0.6%) and the Social Security and National Insurance Trust (0.3%). Foreign investors held 16% of the remaining domestic debt.

Restructuring ideas

There have been suggestions that Ghana would prioritise restructuring its domestic debt. But this begs the question: what does a debt restructuring entail and where does the burden fall especially if haircuts – which can include a reduction in outstanding interest payments – are part of the policy mix?

Ghana’s commercial banks held about 30% of the domestic debt and 31% of the total banking sector assets in 2021. Thus, any attempt to restructure the domestic debt without a compensating policy action could leave the banking sector highly vulnerable to further distress.

Restructuring domestic debt focused solely on haircuts would severely affect asset quality and increase non-performing loans much higher than the current 14.1%.

It would also reduce private sector lending, already under severe strain from 20-year high inflation. Pensions and other institutional investments are also likely to suffer.

When it comes to external debt, Ghana must first seek to restructure it under the principles of the G20 Common Framework. Ghana delayed in applying to join the Framework during the pandemic for fears of losing market access.

The country was eventually locked out of the international capital markets anyway after several sovereign rating downgrades.

Ghana has an opportunity to remedy this and offer a collaborative and constructive platform to engage on external debt restructuring.

Zambia’s recent restructuring exercise offers valuable lessons. All creditors must be treated evenly as any hints of arbitrary treatment will delay the process, as happened in this case.

Way forward

There are six steps Ghana must urgently take to get government finances in order.

Firstly, it must enforce the law when it comes to fiscal responsibility and impose hard sanctions on the finance minister and other ministries who flout it. Ultimately, Ghana must ensure that it lives within its means and hold politicians to account to provide funding plans for their political campaign promises.

Secondly, Ghana must implement the Integrated Financial Management System as part of the broader public financing management reforms and ensure that every transaction is fully captured in the main accounting system. Media reports indicate that only about a third of government transactions are fully captured. This creates many avenues for collusion and corruption.

Thirdly, the government must limit borrowing from the domestic market to compensate for the lack of access to the international capital markets.

Fourthly, President Nana Akufo-Addo must cut down the size of the government through a reshuffle to remove many of those who are not performing and reduce public expenditure. The President does not need to tell Ghanaians that his ministers are “outstanding”, as the citizens would know it if cost of living is indeed improving.

Fifth, the government must urgently convene a broader national stakeholder forum on the economy with all key representative groups including labour, civil society, inter-faith groups, political parties, and business associations, among others.

In 2014 the then opposition ridiculed the idea of a forum. But platforms like this can be valuable for generating new ideas for economic reforms. It will also ensure stakeholder buy-in of any proposed reform programmes.

Lastly, the government must be transparent in its dealings with Ghanaians and the IMF. All data must be fully and transparently disclosed, especially the indebtedness or exposure of the state-owned enterprises and other parastatals.![]()

Theophilus Acheampong, Associate Lecturer, University of Aberdeen

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Follow African Insider on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram

Source: AFP

Picture: Getty Images

For more African news, visit Africaninsider.com