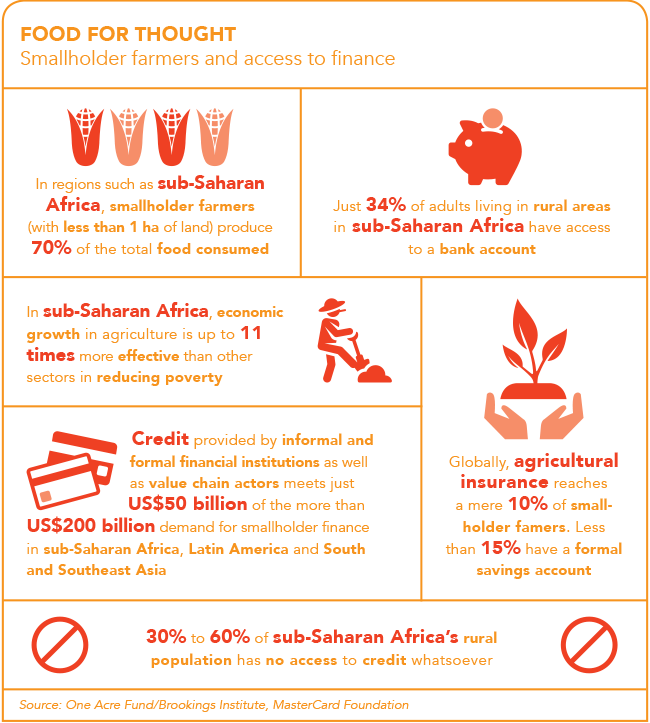

Increasing the productivity of smallholder farmers in developing countries remains key to addressing hunger and poverty for the majority of the world’s most vulnerable populations. One of the greatest gaps in improving smallholder productivity is the large shortfall in financing. It is estimated that credit provided by informal and formal financial institutions, as well as value chain actors, currently meets about just US$50 billion of the more than US$200 billion demand for smallholder finance in the regions of sub-Saharan Africa, Latin America, and South and Southeast Asia.

This is according to a recent report by the Initiative for Smallholder Finance, which found that the projected growth of access to finance of 7% per year from formal institutions and value chain stakeholders would not come close to closing the gap between finance demand and supply over the next five years.

The report identifies some of the key finance needs of commercial smallholder farmers with strong linkages to the value chain and of smallholders in loose value chains. In the first instance, for commercial smallholders, both short-term capital for productive inputs such as fertiliser and improved seed, as well as long-term capital for large investments (for example irrigation systems) are required.

‘To realise the full potential of their agricultural operations, commercial smallholders in tight value chains typically require approximately US$1 500 in short-term financing and US$1 500 to US$2 000 in long-term financing amortised over multiple years,’ according to the report. Smallholder farmers in informal value chains typically require roughly US$500 in short-term capital and a similar amount in long-term capital.

Despite the large deficit that exists between the need for smallholder financing products and what is currently available from governments and the private sector, a number of NPOs and private companies are leading the way in increasing smallholder access to financing in sub-Saharan Africa.

In South Africa, smallholder farmers can apply for loan financing from the Masisizane Fund. The fund is a non-profit company established from unclaimed shares by the Old Mutual Group in 2007, in consultation with the country’s National Treasury. It lends development finance, with a key focus on improving the sustainability of small businesses. According to a statement from Old Mutual, in 2015 the fund invested ZAR100 million to open up the capital-intensive commercial farming industry to small-scale black farmers in the district municipalities of Alfred Nzo in the Eastern Cape and Harry Gwala in KwaZulu-Natal.

One of the beneficiaries of the fund is David Mongoato. He and his wife Selloane worked as teachers for many years before they were able to return to farm in his home province of the Eastern Cape. According to Old Mutual, the Mongoatos now run a thriving 947 ha maize farm near Matatiele, situated close to the Lesotho border. The farm was acquired by the state as part of South Africa’s land reform process, but settlement support from the government did not allow for startup capital. The Mongoatos were able to secure a loan from the Masisizane Fund to purchase crucial equipment such as farm implements, as well as providing startup capital for them and 14 other emerging farmers in the area with whom they have formed a partnership to share some resources.

Several commitments were made by governments, aid agencies and the private sector to increase funding for agricultural development at the African Green Revolution Forum (AGRF) held in Nairobi, Kenya in 2016. At the event, US-based organisation Root Capital announced that it was launching a new partnership with the MasterCard Foundation that will help raise incomes for more than 300 000 smallholder farmers in West Africa.

The MasterCard Foundation committed US$5.2 million to the organisation over five years ‘to support early-stage agricultural businesses that generate transformational impact in rural communities in Côte d’Ivoire, Ghana and Senegal’.

According to Ann Miles, director of financial inclusion and youth livelihoods at the MasterCard Foundation, the partnership with Root Capital will ‘help bring much-needed financing and capacity building to businesses in West Africa that work with farmers otherwise excluded from the formal economy’.

Meanwhile, Diaka Sall, Root Capital GM (West Africa), says the collaboration would aim specifically to ‘accelerate the bankability and growth of more than 100 high-impact, early-stage agricultural businesses with capital needs under US$150 000 and/or business revenues under US$300 000’. This is in addition to piloting an expanded set of advisory services, including leadership development of agribusiness employees and empowering local microfinance institutions to better serve the agricultural sector.

Also at the 2016 AGRF, the Kenya Commercial Bank (KCB) Group announced it would invest US$350 million to finance agriculture business opportunities that could reach some 2 million smallholder farmers. In a statement issued by the AGRF, KCB said of that funding, US$200 million would go toward improving market infrastructure and mobilising farmers, while US$150 million would be channelled through the KCB Foundation to support livestock farmers.

KCB will also work with the MasterCard Foundation, contributing US$30 million yearly to helping smallholder farmers access credit and market information via mobile devices.

At the event, the African Development Bank pledged US$24 billion over the next 10 years – a 400% increase over previous commitments – to help drive agricultural transformation in Africa. Some of this money is earmarked for initiatives that will accelerate access to commercial financing for smallholder farmers.

In a briefing document submitted to the Brookings Institution’s Ending Rural Hunger project – authored by One Acre Fund global senior policy analyst David Hong and senior vice-president (policy and partnerships) Stephanie Hanson – the writers argue that providing smallholder farmers with access to credit is key to unlocking long-term, sustainable gains in farmer productivity and incomes.

Without financing, ‘smallholder farmers cannot afford the relatively high upfront costs of quality seed and fertiliser’. Furthermore, they may not be able to afford the training services needed to maximise seed and fertiliser application.

In addition, without access to credit, smallholder farmers are also forced to sell any crop surplus immediately after harvest, when prices are typically at a seasonal low.

The report presents case studies of institutions currently providing smallholder farmers with access to credit, including the One Acre Fund and Juhudi Kilimo, a microfinance company in Kenya. Both organisations mitigate risk for the lending party by offering asset-based loans that ensure access to farm inputs, as opposed to cash loans.

Organisations, the report states, should also focus on productivity and provide farmers with training and support aimed at mitigating production and price risks – and they should offer appropriate loan terms that take into account the fact that farmer income is based on seasonal crop cycles, which means cash flow is irregular.

According to the report, Juhudi Kilimo provides asset-based loans to more than 20 000 smallholder farmers in Kenya. Its loans are designed to enable farmers to purchase assets (for example dairy livestock or irrigation equipment) that will provide immediate and continuous cash flow. These capital assets are insured and their value is used as collateral in case of default, which protects both farmers and the company.

Founded in 2006 in western Kenya, One Acre Fund, is an agricultural NPO that supplies smallholder farmers with the financing and training they need to increase their incomes and food security. It works with more than 400 000 smallholder farmers in Burundi, Kenya, Malawi, Rwanda, Tanzania and Uganda. The organisation anticipates that by 2020 it will serve 1 million farmers.

‘The majority of the world’s poor are hard-working smallholder farmers who can reach their full potential with access to finance, training and services,’ One Acre Fund founder and executive director Andrew Youn said in a 2016 media statement.

Participating farmers in the One Acre Fund programme receive a complete bundle of agricultural inputs and services on credit, including the delivery of high-quality seeds and fertiliser, training on how to maximise crop yields, and education on how to minimise post-harvest losses.

To accommodate clients, the organisation offers a flexible repayment system: farmers can make payments toward loans in any amount and at any time during the growing season, as long as they complete repayment by the season’s end. In 2015, 99% of One Acre Fund farmers repaid their loans in full and on time. To be eligible for a loan, farmers are required to submit a small down payment of the total loan; regularly meet with a local One Acre Fund field officer; and attend agricultural training sessions.

According to Hong and Hanson, the gap between the demand for agriculture financing and supply can, to a large extent, be attributed to the perceived risk of lending to farmers, whose ‘lumpy and irregular income streams, poor productivity, outmoded agricultural practices, and seasonal crop cycles all pose unique challenges to financial service providers’. However, drawing from their own experience, the writers suggest that microfinance institutions and banks overestimate the risk of smallholder farmer financing, adding that small adjustments to lending criteria could significantly improve repayment rates and reduce risk.