As the role of farmers in Southern Africa is changing, the role of agricultural finance is also evolving. The sharing economy – with the pooling of resources and crowdsourcing – is set to strengthen emerging and smallholder farmers, who often don’t have the collateral to qualify for finance from commercial banks. The large commercial farmers and their agricultural value chain are expected to see a rise in demand for the financing of farming mechanisation and conservation farming, as well as for new opportunities arising from careers in fields such as farming-related technology and management, and food and animal science.

Advancements in technology have already improved the way the agriculture sector accesses finance: via mobile phones, digital channels and electronic payment platforms. One tech-based trend is crowdfunding – the online method of raising finance for a business idea or good cause by asking a large number of people to each donate small amounts – which has been shifting its focus from arts, culture and charity projects to include agricultural ventures. Terms such as ‘crowd-farming’ or ‘herd-funding’ are popping up. There’s hope that such digital platforms may one day provide commercial farmers with the debt or equity finance they need to pay for their inputs (such as livestock, feeds, seeds and fertiliser), farming equipment, storage facilities and farmer development and training.

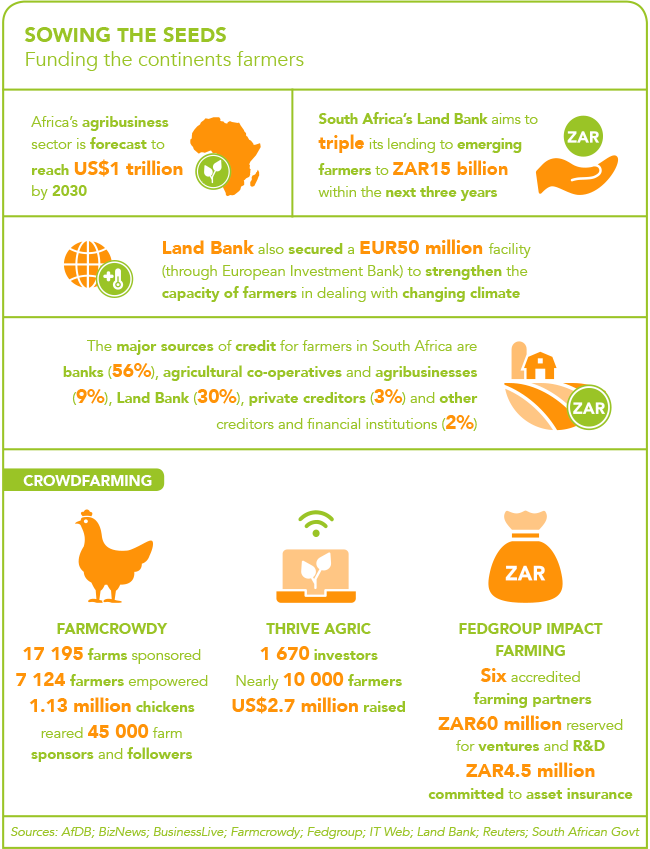

So far, the primary focus has been on production finance for those at the bottom of the agricultural pyramid: emerging and smallholder farmers without sufficient collateral to cover their production input costs. This presents an innovative, informal alternative to commercial banks, agricultural companies, development agencies and development finance institutions. Access to specialised, properly timed agri-finance is fundamental to future-proofing the sector, making it resilient to climate risks (such as drought and flood) and sudden spikes in agricultural input costs, in order to meet Africa’s growing food requirements. The World Bank forecasts that the global demand for food will increase by 70% by 2050, requiring at least US$80 billion in annual investment, mostly from the private sector.

Although crowdfunding is not yet regulated, it has already shown some success. Growsel in Nigeria, for instance, connects underserved smallholder farmers with international lenders. The non-profit agriculture technology (agritech) start-up screens and verifies farmers before allowing them to access capital via its digital marketplace. Growsel (whose motto is ‘small seeds, big impact’) also supports participating farmers with index-based crop insurance and works with field partners to provide training in order to achieve better farming outputs. This approach also leads to improved loan payback, thereby reducing the risk for the lenders.

Farmcrowdy, another African agritech crowdfunding start-up, compares its services to the way online shopping has revolutionised the retail sector. ‘With the availability of online farming, agritech start-ups have changed the face of agricultural investment in Nigeria,’ writes Uduak Ekong on the Farmcrowdy blog. ‘You want to invest in a farm and make [a]profit without worrying about getting your hands dirty? It’s now as easy as clicking a button or downloading an app on your mobile device. Agritech start-ups have served as a bridge to bring two parties together to foster agro-investment.’

She sums up: ‘There are farmers looking for funds to farm and there are potential investors looking for farms to sponsor. Farmcrowdy has drastically transformed agro-investment by serving as this bridge.’

Since its launch in 2016, the multi-award-winning start-up has helped more than 7 000 small farmers across Nigeria raise a total of US$6 million from 2 000 (mostly Nigerian) investors. Online videos and photos assist potential investors in choosing which farm to support and also allow updates on the progress of their crops or livestock. According to Reuters, the typical investment starts from around US$300, which is ‘too little to interest many banks but enough to help keep a small farm going until harvest’.

In South Africa, Livestock Wealth uses the same collective online funding principle as Farmcrowdy and Growsel, but exclusively crowdfunds cattle. ‘It works like a bank fixed deposit where you invest in a cow for a six- or 12- month period with an option to re-invest,’ says the crowd-farming start-up. Its 12-month option means investing in a pregnant cow and the six-month option in a calf, which will eventually be sold for free-range beef with an average return on investment of about 12%. Investors are encouraged to visit their cows in person and can monitor the daily farm activities via Livestock Wealth’s mobile app.

In addition to funding, the cattle farmers also gain access to the formal meat-supply value chain (through Livestock Wealth’s partners Woolworths and Cavalier Foods), as well as to quality healthcare and nutrition for their cows. They further benefit from the real-time animal tracking system, which reduces the risk of stock theft. Even established financial services providers are recognising the value of crowd-sourced farm investment that does not require ownership of land, crops or livestock – while having a positive impact on the farming sector. FedGroup, a diversified family-owned financial services business that was founded in 1990, now includes ‘impact farming’ among its offerings. And it intends to strengthen South Africa’s commercial farming sector rather than smallholder farmers.

The concept is simple: ‘You buy. We farm. You earn’. Investors purchase assets on one of the group’s farms and receive income from the harvest. The website explains how it works: ‘Download the FedGroup app. Choose from blueberries, honey or solar. Or buy a mixed bundle of assets. How much you invest is up to you. Take ownership in minutes, not months.’ If you choose to invest in blueberries, you can expect an average earning per annum of 12% over the eight-year lifespan of the blueberry bush, according to FedGroup. At the same time, the company ensures the positive economic, social and environmental impact of its farming ventures by measuring factors such as how water-wise the operations are, how many jobs are being created and whether the supply chain is ‘ethical’.

While size matters in farming, Wandile Sihlobo, head of agribusiness research at the Agricultural Business Chamber (Agbiz), says the national discussion on the future of South Africa’s agriculture should focus on boosting productivity across all farms rather than on their sizes. He argues in Business Day: ‘Big farms are key to national food security and driving exports, while small farms continue to serve local markets, where big players rarely participate, due to numerous reasons which could range from economic viability, traditional business models and other issues.’

The World Bank notes the importance of lowering the operating costs for dealing with smallholder farmers, and underlines the significance of large-scale agri-finance: ‘The development of agriculture requires financial services that can support larger agriculture investments and agriculture-related infrastructure that require long-term funding (given that currently transportation and logistics costs are too high, especially for landlocked countries), a greater inclusion of youth and women in the sector, and advancements in technology (both in terms of mechanising the agricultural processes and leveraging mobile phones and electronic payment platforms to enhance access and reduce transaction costs).’

To allow commercial farmers to ‘shop around’ for finance, the Western Cape Department of Agriculture has published a document on sources of finance for agricultural businesses. These include long-standing agricultural companies (the former agricultural co-operatives) such as Afgri and Kaap Agri. The latter is listed on the JSE and well-known for its successful Agrimark retail brand. Kaap Agri offers a range of financial services in support of its core retail business. It is headquartered in Malmesbury, Western Cape, and has more than 200 operating points across the Western Cape, Northern Cape, Eastern Cape, Gauteng, Mpumalanga, Limpopo and in Namibia.

Afgri offers loans and agricultural insurance through its Unigro subsidiary while its Gro-Capital Financial Services focuses on corporates involved in agriculture and food production, to whom it provides debt origination, forex and commodity trading, specialised finance and broking services.

Meanwhile Peulwana Agricultural Financial Services specialises in small- and medium-scale farmers and agro-processors, offering input finance and market linkages to mainstream markets. Capital Harvest offers niche products such as production finance for fruit-exporting farmers, which the company says is unique because ‘it’s made available in accordance with the cash-flow needs against a cession of the harvest as main security and by managing the associated risks in the value chain – no tangible security such as bonds are required’. Another tailor-made product is the Grain Input Finance Facility, which is aimed at grain farmers in higher-risk areas.

It’s in our collective interest that Africa’s farmers receive innovative, specialist finance and insurance products to boost their production. After all, their success will determine the state of our food basket.