Oceans have long been a vital element in Africa’s history. The continent controls enormous marine riches: about 13 million km2 of sea territory. Out of 54 African countries, 38 are coastal; with around 35 000 km of coastline. Much of this is underexploited.

One of the marine sectors that is generating particular excitement is fisheries. Currently, the fishing industry supports more than 12 million African livelihoods. In all, the annual value of the continent’s maritime industry is estimated at an impressive US$1 trillion.

At a time when many other sectors are struggling, it’s no wonder watery resources are appearing in numerous policy documents. ‘Concepts such as the “blue economy”, “blue capital” and “blue growth” have emerged and become entrenched in policy discussions around the future of the oceans,’ write environmental scholars Maria Hadjimichael and Irmak Ertör in a 2019 editorial. The challenge is to take advantage of these opportunities while also protecting fragile ecosystems.

In the words of Cedric Boisrobert and John Virdin of the World Bank’s Africa Region Environment and Natural Resource Management Unit, African countries are starting to achieve this balancing act, understanding ‘that their fisheries and supporting ecosystems are key to maintaining many livelihoods and that they need to invest in improving the governance of the sector and management of the resources’.

The AU has become very focused on the marine economy – going so far as to call it the ‘new frontier of the African renaissance’. It is a central piece in the AU’s most important policy proposals: the 2050 Africa’s Integrated Maritime strategy and Agenda 2063.

The buzz about the sector was evident earlier this year at the AU Summit in Addis Ababa. Here, a devoted blue economy event was organised by Seychelles on the margins of the main conference.

‘I know that many African countries and regional bodies are increasing their co-operation in order to increase knowledge about the blue economy and adopt the policies that can help reap its immense potential,’ UN secretary-general António Guterres said at the event.

‘We hope for bold action that will safeguard marine ecosystems and resources, advance progress across all the sustainable development goals and help us address the worsening climate crisis.’

Thomas Kwesi Quartey, vice-chair of the AU Commission (AUC), added his voice to this appeal, saying that Africa was well prepared to make the blue economy ‘a vehicle of change that will carry Africa to the next frontier’.

In June, the UN was scheduled to convene the Oceans Conference in Lisbon to discuss co-operation between African and other nations to protect the world’s ocean environments. The first such conference was held in Nairobi in 2018, and the 2020 event – albeit postponed as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic – is to be co-hosted by Portugal and Kenya, again emphasising Africa’s centrality to these debates.

The blue economy takes various forms across the continent. Countries as diverse as South Africa, Kenya and the Seychelles have different approaches and priorities. South Africa, Mauritius and Seychelles have been recognised for their pioneering national initiatives, while countries such as Kenya, Nigeria and Ghana are also making concerted efforts to develop their maritime economies.

‘We are working actively with the African Union Commission to develop model blue economy policy and put in place tools that may be adapted to each country’s specification,’ Seychelles President Danny Faure said at the blue economy side event held at the Tokyo International Conference on African Development in 2019.

The countries with the most potential are not necessarily the richest. Somalia, for example, has an enviably long coastline – more than 3 000 km – and seas rich with nutrients. Unfortunately, its ocean economy has been limited by the threat of piracy, but greater international naval vigilance in recent times means that Somalia’s blue economy has enormous potential.

Madagascar, too, boasts an enormously long coastline and is well placed on Indian Ocean trade routes. It has drawn US$2.7 billion in promised Chinese investment in shipyards, aquaculture and fisheries over a 10-year period. One promising project is the cultivation of sea cucumbers, which have a ready and lucrative Chinese market. NGO Blue Ventures trains locals in this form of aquaculture.

Kenya’s blue economy currently contributes a mere 2.5% to its GDP, although the country has access to extremely rich fish resources such as tuna stocks. The East African nation has recently attracted major infrastructural investment from several powerful international partners. Last year, Japan agreed to invest in improving the port facilities at Mombasa. ‘Japan will work closely with Kenya to secure its ocean-based economy and ensure there are no maritime security threats,’ said Ryōichi Horie, Japanese ambassador to Kenya.

This came close on the heels of the announcement of a partnership with Canada to build the country’s fisheries infrastructure. ‘We are going to construct a marine park in Kenya in conjunction with Canada to add to tourism attraction sites as well as leisure and learning activities,’ said Micheni Ntiba, principal secretary of Kenya’s Fisheries, Aquaculture and the Blue Economy.

Also last year, Kenya partnered with the World Bank on a US$100 million fisheries project, aimed at ensuring sustainable fishstock productivity and creating local economic benefits over five years. At least one national mariculture resource and training centre will be built. According to the World Bank, ‘this new facility will undertake the much-required research in fish-breeding towards supplying commercial hatcheries with improved broodstock for fast and efficient production’.

Namibia is in the process of finalising a blue-economy national policy, aiming to implement a marine governance and management system by 2022. Its ocean industries (which comprise fisheries, mining, transport and tourism), account for about 28.8% of the country’s GDP. According to Namibia’s acting Minister of Fisheries and Marine Resources, Albert Kawana, the government places a high priority on developing the sector in an environmentally sustainable way. This, despite certain challenges: towards the end of 2019, Namibia’s blue economy gains were overshadowed by the ‘fishrot files’ scandal. The release of files by WikiLeaks exposed the bribing of high-ranking Namibian officials by an Icelandic fishing company in order to obtain a fishing quota. The scandal eventually resulted in the forced resignation of several Namibian government ministers and other officials.

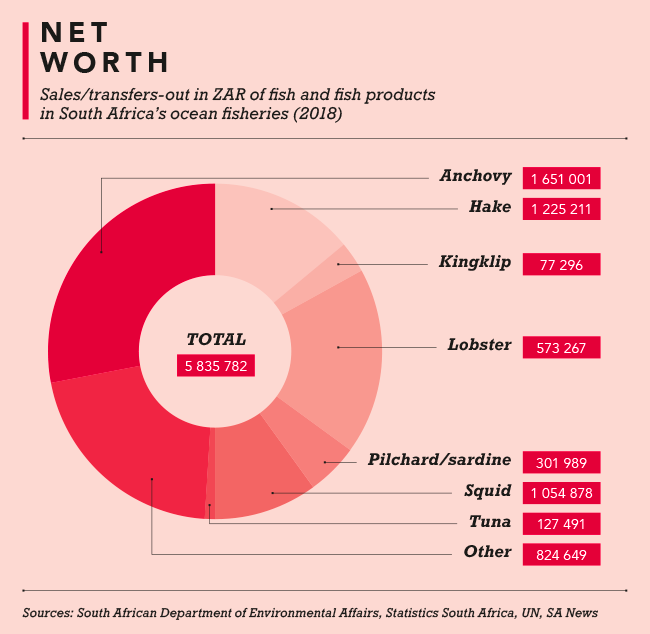

South Africa has thousands of kilometres of coastline and sits at the heart of one of the world’s most-established and busiest trade routes. It is estimated that, by 2033, the blue economy could add ZAR177 billion to the country’s GDP and create up to 1 million jobs. The government’s blue-economy strategy is embodied in its Oceans Economy Lab, which forms part of the Operation Phakisa programme to fast-track economic growth and job creation. Tourism is also set to be an important element in the country’s blue-economy strategy. Coastal and marine tourism has been forecast to create at least 116 000 jobs by 2026. Shark cage diving and whale watching are two popular tourist activities that appeal to an international interest in wildlife and ecology.

Elsewhere, tourism bodies are also turning their attention to the seas. All agree that there’s great potential to diversify the sector beyond land-based wildlife tourism, which is currently the premier tourist attraction on the continent.

For example, as African Tourism Board chair Cuthbert Ncube said in February this year, after a visit to Tanzania’s Sinda Island, ‘when we talk about tourism in Tanzania, we always talk about Mount Kilimanjaro. But we have so many amazing tourist attractions that need to be exposed. Let us expose our islands in this continent to local, regional and international tourists’. Tanzania boasts several protected marine parks, due to be promoted as the ‘new tourist corridor’.

It’s clear that marine resources represent a glowing opportunity for coastal African countries – provided they are responsibly and sustainably managed, and countries co-operate on preserving this precious and shared resource.

As the AUC’s Quartey puts it, ‘we must also unite, collaborate and overcome challenges we are facing together in the management and use of our maritime resources. Our goal is common and achievable’.